In one of the most untouched and remote rainforests in the world, scientists have discovered some sixty new species, including a chocolate-colored frog and a super-mini dung beetle. The species were uncovered in Southeastern Suriname during a Rapid Assessment Program (RAP); run by Conservation International (CI), RAPS involve sending teams of specialists into little-known ecosystems to record as much biodiversity as they can in a short time. In this case, sixteen researchers from around the world had about three weeks to document the region’s biodiversity.

“Suriname is one of the last places where an opportunity still exists to conserve massive tracts of untouched forest and pristine rivers where biodiversity is thriving,” says Trond Larsen, the Director of the Rapid Assessment Program at Conservation International. “Ensuring the preservation of these ecosystems is not only vital for the Surinamese people, but may help the world to meet its growing demand for food and water as well as reducing the impacts of climate change.”

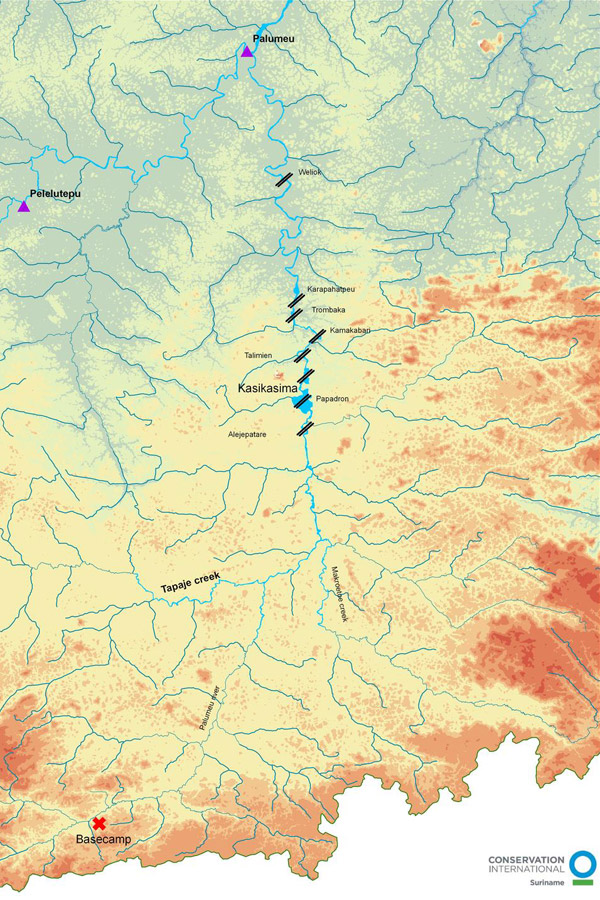

The biologists visited four sites along the upper Palumeu River watershed, including mountains to lowlands. They catalogued 1,378 species in total (an average of 86 per researcher), of which about sixty are thought new to science.

Suriname is one of the most-heavily forested countries in the world: around 91 percent of the country is still covered in forest according the FAO, while the small country’s population remains small. However, mining, hydropower, and other industries are beginning to take their toll. In fact, the team measured high levels of mercury in the river despite being far from mining sites, but Larsen says the mercury is likely coming from mining and energy operations in other countries.

The region is a part of the Guiana Shield, a massive stretch of rainforest situated above the Amazon, which covers northern South America, including Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname, and portions of Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil. The Guiana Shield is sometimes considered a part of the Amazon rainforest, though not of the Amazon Basin. Although lesser known than many of the world’s rainforests, the Guiana Shield makes up about a quarter of the world’s total rainforests and is among the world’s least degraded.

“I have conducted expeditions all over the world, but never have I seen such beautiful, pristine forests so untouched by humans. Southern Suriname is one of the last places on earth where there is a large expanse of pristine tropical forest,” noted expedition leader and ant expert Leeanne Alonso. “The high number of new species discovered is evidence of the amazing biodiversity of these forests that we have only just begun to uncover.”

Scientists believe the so-called ‘cocoa’ frog is new to science. Photo by: Conservation International.

The ‘lilliputian beetle’ may not only be a new species, but a new genus. It is the smallest dung beetle yet discovered in the Guiana Shield, and the second smallest in all of South America. Dung beetles are nature’s recyclers, mitigating disease and turning over nutrients. Photo by: Conservation International.

This new katydid is distinct enough to make its own genus. Note its unusually long legs. Photo by: Conservation International.

This larger fruit-eating bat (Artibeus planirostris) was the most commonly sighted of the 28 species bats catalogued. They use their sharp teeth to eat large fruits and may be important seed disperser. Photo by: Conservation International.

Scientists were able to capture what they call a ‘very rare event’: a wolf spider eating a poison dart-frog (Amereega trivitatta). Photo by: Conservation International.

Tiny juvenile leafhopper (only 5 millimeters) with waxy substances coming off its abdomens. Scientists aren’t sure why leafhoppers do this but it may be to confuse predators. Photo by: Conservation International.

Ants, one of 149 species noted, consuming a dead insect. Photo by: Conservation International.

A delicate slender opossum (Marmosops parvidens), one of 39 species of small mammals. Photo by: Conservation International.

Map showing field sites of RAP in Southeastern Suriname. Photo by: Conservation International.

Related articles

Jaguar v. sea turtle: when land and marine conservation icons collide

(05/16/2012) At first, an encounter between a jaguar (Panthera onca) and a green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) seems improbable, even ridiculous, but the two species do come into fatal contact when a female turtle, every two to four years, crawls up a jungle beach to lay her eggs. A hungry jaguar will attack the nesting turtle, killing it with a bite to the neck, and dragging the massive animal—sometime all the way into the jungle—to eat the muscles around the neck and flippers. Despite the surprising nature of such encounters, this behavior, and its impact on populations, has been little studied. Now, a new study in Costa Rica’s Tortuguero National Park has documented five years of jaguar attacks on marine turtles—and finds these encounters are not only more common than expected, but on the rise.

Photos: 46 new species found in little-explored Amazonian nation

(01/25/2012) South America’s tiniest independent nation still hides a number of big surprises: a three week survey to the sourthern rainforests of Suriname found 46 potentially new species and recorded nearly 1,300 species in all. Undertaken by Conservation International’s (CI) Rapid Assessment Program (RAP) the survey found new species of freshwater fish, insects, and a new frog dubbed the “cowboy frog” for the spur on its heel. While Suriname may be small, much of its forest, in the Guyana Shield region of the Amazon, remains intact and pristine. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 91 percent of Suriname is covered in primary forests, however this data has not been updated in over two decades.

Indigenous peoples in Suriname still wait for land rights

(07/31/2011) Legal rights and recognition for the diverse indigenous peoples of Suriname have lagged behind those in other South American countries. Despite pressure from the UN and binding judgments by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Suriname has yet to recognize indigenous and tribal land rights, a situation that has disconnected local communities from decisions regarding the land they have inhabited for centuries and in some cases millennia. A new report, Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Conservation in Suriname: A Review outlines how this lack of rights has alienated indigenous communities from conservation efforts in Suriname. Instead of having an active say in the creation of conservation reserves, as well as their management, decisions on indigenous lands have traditionally been imposed from the ‘top-down’ either by government officials or NGOs.

(01/27/2009) After a year studying marine biology at Moss Landing Marine Labs, Liz McHuron headed off to the little-known nation of Suriname to monitor leatherback sea turtles. Her responsibilities included implementing a conservation strategy for a particular beach, moving leatherback nests in danger of flooding, and educating volunteer workers on the biology, behavior, and conservation efforts of the world’s largest, and most unique, marine turtle. I visited McHuron during her time at the beach of Galibi in Suriname; she proved to be the sort of scientist who refused to be deterred: breathtaking humidity or downpours, fer-de-lances on the beach or jaguars, Liz was always on the move, always working to aid the critically-endangered leatherbacks while studying them with the thoroughness inherit in a born scientist.

Account of 18th century Amazon adventurer to be published for the first time

(08/11/2008) After establishing his ingenious classification system in 1735, Carl Linnaeus, the greatest naturalist of his era, sent young and eager followers to all parts of the world to help him in the goal of collecting and cataloguing the world’s species. It was a project unlike any before; Swedish naturalists, often referred to as Linnaeus’s apostles, roamed as far as Japan, South America, Australia, and the Arctic with the same goal in mind—describing species according to Linnaeus’s system.