Video of illegal gold mining operations that have turned a portion of the Amazon rainforest into a moonscape went viral on Youtube after a popular radio and TV journalist in Peru highlighted the story.

Last week Peruvian journalist and politician Güido Lombardi directed his audience to video shot from a wingcam aboard the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), an airplane used by researchers to conduct advanced monitoring and analysis of Peru’s forests. The video quickly received more than 60,000 views on Youtube.

The attention generated by the broadcast is significant because the issue of gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon isn’t well known, despite its widening impact.

Güido Lombardi voiceover detailing the damage caused by gold mining in Madre de Dios in southeastern Peru (Spanish).

According to Greg Asner, the Carnegie Department of Global Ecology scientist who led the development of the CAO, more than 50,000 hectares have been affected by gold mining in just the southern part of the department of Madre do Dios. A soon-to-be-published paper, co-authored with members of Asner’s team as well as Peruvian researchers, will show that the rate of expansion has nearly tripled in recent years, climbing from 2,166 hectares per year prior to 2008 to 6,145 thereafter.

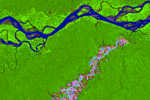

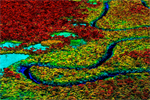

While the numbers may seem abstract, seen from above, the extent and totality of the devastation is astonishing. Vast areas of wildlife-rich rainforests have been annihilated, while normally clear-flowing streams have been converted to muddy cesspools. Streams draining mining areas run blood-red and carry toxins and heavy metals like mercury to downstream towns and villages. Virtually all this mining is illegal.

Screen capture from the video of the CAO flying over illegal gold mines in Peru

Given the growing damage — including social problems like violent conflict, crime, poor labor conditions, human trafficking and prostitution — getting a handle on the activity is a priority for Peru’s Ministry of Environment. The agency, better known as MINAM, has partnered with Asner’s team to track mining in near real-time.

“CAO’s sensors provide detailed information on patterns of degradation that are specific to gold mining; practically in real time,” Ernesto Raez, a senior official at MINAM, told mongabay.com. “We are very interested in the ability of the technology onboard CAO to detect illegal gold mining in the eastern foothills of the Andes (where it is much less visible and easier to hide) and to detect chemical traces of gold mining in the waters, particularly the presence of heavy metals.”

Raez says that illegal gold mining is also afflicting high elevation areas in the Titicaca Lake basin.

“The dimension of illegal mining in the Titicaca basin, particularly at the sources of the Ramis river, is even more shocking than in the jungle (if possible), with massive destruction of precious highland wetlands with heavy machines. These are giant operations. Arsenic has been found in the Titicaca Lake.”

Ernesto Raez describing the impact of gold mining (Spanish).

The Peruvian government doesn’t yet have an estimate for the total extent of gold mines across the country, but Raez estimates that informal mining may involve 150,000 people across the country, suggesting it is well entrenched and therefore potentially very difficult to address.

Asner says whatever the utimate number, it is clear that gold mining is much more pervasive than previously estimated.

“These numbers are much higher than previous reports, and we have fully validated them by combining CLASlite [Asner’s satellite-based deforestation and forest degradation tracking system that is currently being used extensively by MINAM], CAO and clandestine fields surveys,” Asner told mongabay.com. “Working on this problem with Ernesto and the rest of MINAM is a top priority for the CAO team.”

Related articles

Scientists discover high mercury levels in Amazon residents, gold-mining to blame

(05/28/2013) The Madre de Dios region in Peru is recognized for its lush Amazon rainforests, meandering rivers and rich wildlife. But the region is also known for its artisanal gold mining, which employs the use of a harmful neurotoxin. Mercury is burned to extract the pure gold from metal and ore producing dangerous air-borne vapors that ultimately settle in nearby rivers. ‘Mercury in all forms is a potent neurotoxin affecting the brain, central nervous system and major organs,’Luis Fernandez, an ecologist and research associate at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, told mongabay.com. ‘At extremely high exposure levels, mercury has been documented to cause paralysis, insanity, coma and death.’

(12/08/2012) The world’s largest rainforest is in the midst of a mining boom fueled by high mineral prices, reveals a new assessment of the Amazon’s resources.

Gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: a view from the ground

(03/15/2012) On the back of a partially functioning motorcycle I fly down miles of winding footpath at high-speed through the dense Amazon rainforest, the driver never able to see more than several feet ahead. Myriads of bizarre creatures lie camouflaged amongst the dense vines and lush foliage; flocks of parrots fly overhead in rainbows of color; a moss-covered three-toed sloth dangles from an overhanging branch; a troop of red howler monkeys rumble continuously in the background; leafcutter ants form miles of crawling highways across the forest floor. Even the hot, wet air feels alive.

High gold price triggers rainforest devastation in Peru

(10/11/2011) As the price of gold inches upward on international markets, a dead zone is spreading across the southern Peruvian rain forest. Tourists flying to Manu or Tambopata, the crown jewels of the country’s Amazonian parks, get a jarring view of a muddy, cratered moonscape … and then another … and another in what the country boasts is its capital of biodiversity. While alluvial gold mining in the Amazon is probably older than the Incas, miners using motorized suction equipment, huge floating dredges and backhoes are plowing through the landscape on an unprecedented scale, leaving treeless scars visible from outer space. Sources close to the Peruvian Environment Ministry say the government is considering declaring an environmental emergency in the region, but emergency measures passed two years ago were not enough to contain the destruction, and some observers doubt that a new decree would have any more impact.

Picture of the day: the high price of gold for the Amazon rainforest

(08/11/2011) The surging price of gold is impacting some of the world’s most important ecosystems: tropical forests.

Demand for gold pushing deforestation in Peruvian Amazon

(04/19/2011) Deforestation is on the rise in Peru’s Madre de Dios region from illegal, small-scale, and dangerous gold mining. In some areas forest loss has increased up to six times. But the loss of forest is only the beginning; the unregulated mining is likely leaching mercury into the air, soil, and water, contaminating the region and imperiling its people. Using satellite imagery from NASA, researchers were able to follow rising deforestation due to artisanal gold mining in Peru. According the study, published in PLoS ONE, Two large mining sites saw the loss of 7,000 hectares of forest (15,200 acres)—an area larger than Bermuda—between 2003 and 2009.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.