Commercial fishing allowed in 97 percent of the world-famous Phoenix Islands marine protected area

In 2010 President Anote Tong of Kiribati made a historic pledge, committing to protect the waters around his island nation in a massive marine protected area. He said the gesture represented Kiribati’s contribution to protecting the environment and he urged industrial countries to do the same by cutting their greenhouse gas emissions, which threaten low-lying islands with rising sea levels. The commitment raised Tong’s profile, winning him international accolades, and boosted the tiny country’s standing in the fight against climate change. But since 2010 questions have begun to emerge about the extent of Tong’s commitment.

The controversy

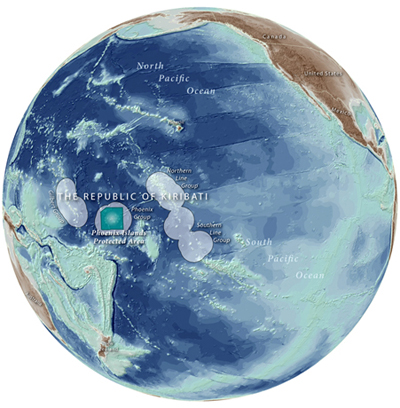

In a 2010 interview with mongabay, President Anote Tong of Kiribati proudly boasted that the entire 408,250 square kilometers (~150,000 square miles) Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) – a large marine park roughly the size of California — was off limits to commercial fishing. Partly for this achievement, he has received two prestigious awards for environmental leadership.

According to the PIPA management plan, however, only 3.1 percent of the reserve area is strictly protected from commercial fishing. Protection is extended to the reefs around the uninhabited islands within the reserve – an area smaller than the San Francisco Bay Area. Offshore fishing vessels can legally exploit the remaining 97 percent of the UNESCO-designated marine protected area.

Image courtesy of phoenixislands.org |

And so they do. More than 400 vessels fish legally inside PIPA, said Betarim Rimon, information officer for PIPA in his online office hours. Fishing fleets come from the U.S., EU, South Korea, China, Japan and other nations. A purse seiner (a typical fishing vessel) catches on average 32 tons of tuna per day.

“For Kiribati to allow commercial fishing in almost 100 percent of the PIPA protected area is at odds with the bold promises of PIPA’s objective as heralded by President Tong when he first launched it,” said Seni Nabou, Pacific Political Advisor for Greenpeace.

Dr. Gregory Stone, Executive Vice President of Conservation International and the person who first proposed the creation of PIPA, replies that such measures do not get implemented overnight. Restriction of all fishing has always been part of the phased approach and will happen soon, as planned.

“I can only guess that some confusion probably resulted from mixing up plans and aspirations with the current status of the management plan,” said Stone.

The Math

Selling fishing licenses to foreign fleets accounts for around $27 million per year, more than 40 percent of the Kiribati’s national revenue. To recoup this income, President Tong has requested financial compensation (sometimes called “reverse fishing licenses”) to close the remaining 97 percent of PIPA to fishing.

In this type of conservation effort, donors pay the country an amount comparable to what it would receive from selling real fishing licenses, on condition that the fish are left in the ocean instead. “Reverse fishing licenses’ are also referred to as compensation for lost revenue.

Brightly colored christmas tree worms (Spirobranchus spp.) delicately filter feed from their home in a Porites spp. coral colony on Enderbury Island. © Jim Stringer. Within the Phoenix Islands Protected Area lie eight of atolls, two submerged reef systems, approximately 14 submerged seamounts (underwater mountains) as well as deep-sea and open-ocean environments which have been described as among the most isolated and free from human impact left on the planet, resembling what the ocean might have looked like a thousand years ago, according to Conservation International. |

The way this idea works in practice is that donors put their contributions into a trust fund. The lump sum is then invested in securities, government treasury notes and other financial products. The interest it generates (on average 5 percent less the trust management fee) is then to be used for conservation: to pay for both management of the protected area and compensation for loss of exploitation revenue.

In principle, “reverse fishing licensing” is the marine analog to paying a tropical country for not cutting down their forest (the so-called REDD program). However, the idea of paying poor countries to protect their natural resources recently suffered a major setback with the failure of the Yasuni plan. President Correa of Ecuador had challenged the world to donate $3.6 billion into the Yasuni trust fund. The interest was to be used as compensation for not exploiting oil reserves in one of the most biodiverse forests in the Amazon basin. But as insufficient funds were raised, he scrapped the plan and went for exploitation.

In his book Underwater Eden, Stone describes how the idea for financial compensation developed in the case of PIPA. In the initial negotiations, Kiribati had requested that a trust fund be set up with more than $50 million. Eventually, a compromise was reached to aim for raising $13.5 million by the end of 2014, which would provide sufficient compensation to close an additional 25 percent of the marine park.

The PIPA trust fund just managed to raise $5 million towards its goal. Conservation International donated half of the money, the government of Kiribati – the other half. The interest generated by this amount would probably go towards the cost of PIPA’s management not leaving much for compensation, according to Stone, who also serves as the trust chairman.

“This $5 million is a key step in our long term plans to attract new investment. The trust fund will grow larger, we have other interested donors we are working with,” said Stone.

Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis)

The alternative

Requiring any monetary compensation belies President Tong’s boast that PIPA was his country’s “gift to the world”, argue some. Furthermore, Kiribati wouldn’t necessarily lose income from fishing licenses even if it closed all of PIPA to commercial fishing without waiting for compensation money from the trust. The marine park constitutes only 11 percent of Kiribati’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Fisheries scientists quoted in a story by Christopher Pala in Earth Island Journal believe that commercial fishing ships can catch the same amount of fish in the remaining 89 percent of Kiribati’s EEZ.

“Fleets would be able to fill their quota. The Pacific is big and the area – while a reasonable scale – is comparatively small,” said Nabou.

Marine protected area “spillover effect” is a widely studied phenomenon. Researchers show over and over again that when an area of ocean is closed off to fishing and marine life can reproduce safely, fish catches just outside the borders of the reserve are higher than anywhere else.

Galapagos Island Marine Reserve: the highest intensity of fishing occurs right at reserve borders, indicating that fishers expected greater abundance there. (Map courtesy of the Galapagos National Park Service)

The other encouraging news for the initiative is that an immediate closure of the entire PIPA to fishing has political support in Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati. In an interview for IPS, Kiribati’s ex-president Teburoro Tito called for the immediate closure of PIPA to save the national honor.

This suggests that President Tong’s promise may indeed become a reality. When that day comes, Kiribati’s bountiful marine life will be much better for it.

Related articles

(05/15/2013) With islands and atolls scattered across the ocean, the small Pacific island states are among those most exposed to the effects of global warming: increasing acidity and rising sea level, more frequent natural disasters and damage to coral reefs. These micro-states, home to about 10 million people, are already paying for the environmental irresponsibility of the great powers.

As a tiny island nation makes a big sacrifice, will the rest of the world follow suit?

(09/15/2010) Kiribati, a small nation consisting of 33 Pacific island atolls, is forecast to be among the first countries swamped by rising sea levels. Nevertheless, the country recently made an astounding commitment: it closed over 150,000 square miles of its territory to fishing, an activity that accounts for nearly half the government’s tax revenue. What moved the tiny country to take this monumental action? President Anote Tong, says Kiribati is sending a message to the world: ‘We need to make sacrifices to provide a future for our children and grandchildren.’