Palm oil being used to perpetuate fraud, land-grabbing in Papua New Guinea

Developers are seeking palm oil concessions to as a means to circumvent restrictions on industrial logging in Papua New Guinea, finds a new study published in the journal Conservation Letters.

The research, led by Paul Nelson and Jennifer Gabriel of James Cook University, is based on analysis of 36 proposed oil palm concessions covering nearly 950,000 hectares in PNG. The study assessed the likelihood of the concessions coming to fruition based on land suitability, the capacity of the company to develop the concession, and the existence of conflicting land claims in the concession areas. It found that only five concessions, covering 181,700 ha, are likely to be developed. Tellingly, several of the companies seeking concessions have a history of logging, but little or no experience with palm oil plantation development.

Forest conversion for an oil palm plantation in Indonesia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

“We studied 36 oil palm proposals with plantings planned for 948,000 ha, but we expect that only five plantations covering 181,700 ha might eventuate,” said Nelson in a statement. “The most likely scenario in years to come is large-scale clearing and extraction of timber with little of the land being converted to sustainable agricultural production. It is crucial that the real intentions of developers are understood and highlighted so the PNG Government can manage the situation appropriately.”

Map of Papua New Guinea showing provinces and suitability for oil palm cultivation (source Trangmar et al. 1995). Province acronyms are: C, Chimbu; E.H., Eastern Highlands; S.H., Southern Highlands; W.H., Western Highlands. Caption and image courtesy of Paul Nelson et al (2013).

The authors argue that companies are using so-called Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs) as a way to get around restrictions on industrial logging on customary lands. SABLs are a type of license that converts customary ownership — “the dominant form of land tenure in PNG” — to long-term leases that can be controlled by a corporation.

“Most of the developers in PNG are clearing forest with no intention of cultivating oil palm,” said Nelson. “Instead they’re using agricultural leases to circumvent restrictions on logging.”

“Under forestry guidelines loggers are not permitted to export raw logs from areas covered by new timber permits, but if the same companies are granted the lease they can obtain a forest clearance authority that allows them to export logs,” he said. “If someone wants to make money from cutting down trees and selling the logs, the easiest way has been to apply for a Special Agricultural and Business Lease.”

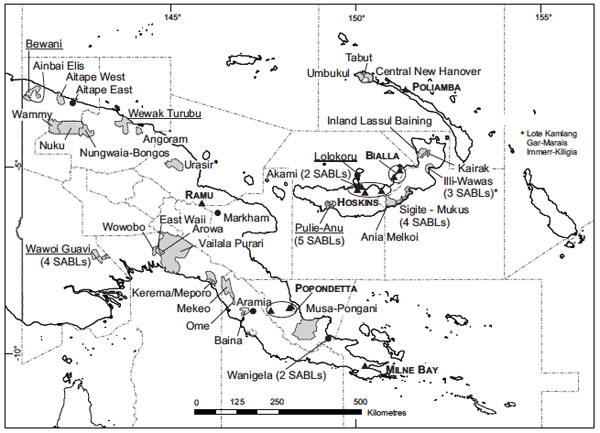

Location of operating palm oil mills (triangles) and Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs) with stated intentions of growing oil palm (grey shading, except where maps were not available, in which case the approximate location is shown as a black point). The five SABLs in which commercial oil palm plantations are most likely to eventuate are underlined. For full names, areas and other details of the SABLs, see Table S1. The areas of commercial oil palm plantations in 2012, associated with the palm oil mills shown and including smallholder blocks, totaled 65,728 ha in Hoskins, 25,020 ha in Bialla, 21,795 ha in Popondetta (Higaturu), 12,168 ha in Milne Bay, 11,295 ha in Ramu and 8,177 ha in Poliamba (PNGPOC 2013). Caption and image courtesy of Paul Nelson et al (2013).

SABLs have expanded rapidly in PNG: the study notes that between 2003 and 2011 — when SABLs were suspended due to public outcry — some 5.5 million hectares, or 12 percent of the country’s land mass, were granted as SABLs. In other words, SABLs are being used to perpetuate a massive land grab, according the authors

“A large-scale land grab is occurring in PNG under the guise of oil palm development, but where there is real oil palm production it is sustainable.”

The situation is not unique to PNG. In the mid-2000s environmentalists reported a similar approach being used by forestry companies operating in Indonesian Borneo. Vast areas were stripped of trees and never planted with oil palm. Not only did Kalimantan lose forest cover, but promised investment and jobs failed to materialize.

PNG now faces a similar risk, one that could dispossess traditional owners of their land.

“The leases also mean land tenure is converted from customary ownership to long-term corporate leases and this is not necessarily in the best interest of the customary owners if the ultimate use of the land is unsustainable,” said Nelson.

PNG was the world’s sixth largest producer of palm oil in 2012, according to U.N. data. Background photo shows an oil palm plantation in New Guinea.

CITATION: Paul Nelson et al (2013). Oil palm and deforestation in Papua New Guinea. Conservational Letters. doi:10.1111/conl.12058.

Related articles

‘National scandal:’ foreign companies stripped Papua New Guinea of community-owned forests

(07/30/2012) Eleven percent of Papua New Guinea’s land area has been handed over to foreign corporations and companies lacking community representation, according to a new report by Greenpeace. The land has been granted under controversial government agreements known as Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs), which scientists have long warned has undercut traditional landholding rights in the country and decimated many of Papua New Guinea’s biodiverse rainforests. To date, 72 SABLs have been granted—mostly to logging companies—covering an area totaling 5.1 million hectares or the size of Costa Rica.

Palm oil giant to produce 100% segregated, RSPO-certified palm oil

(05/23/2012) 100 percent of New Britain Palm Oil Limited’s palm oil will be eco-certified, segregated, and fully traceable by the end of the year, reports the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

Losing our pigs and our ancestors: threats to the livelihoods and environment of Papua New Guinea

(10/27/2011) In 1968, distinguished anthropologist Roy Rappaport wrote a seminal publication of human ecology: ‘Pigs for the Ancestors: Rituals in the Ecology of a New Guinea People’ which integrated cultural ritual with the necessity of maintaining pre-existing relationships with the environment. Documenting the behavior activities of the Tsembaga Maring tribe in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, Rappaport recognized how various activities of the tribe’s intrinsic culture was a direct product of that peoples’ relation with their natural environment.

Primary forest best for birds in Papua New Guinea

(09/26/2011) A new survey recorded 125 birds in Papua New Guinea’s Waria Valley, of which an astounding 43 percent were endemic to the island. The survey, published in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science, was the first of its kind for the rainforest-studded valley and found that bird populations were most diverse and abundant in primary forests. The bird surveys were carried out in four different habitats including primary forest, primary forest edges, secondary forest edges, and agricultural landscape.

Papua New Guinea suspends controversial grants of community forest lands to foreign corps

(05/06/2011) The government of Papua New Guinea yesterday suspended its controversial Special Agricultural and Business Leases program which has granted logging and plantation development concessions to mostly foreign corporations across 5.2 million hectares of community forest land, reports the Courier-Post