Conversion of primary rainforests for industrial agriculture in Costa Rica slows despite population increase and growing exports.

Costa Rica’s ban on clearing of “mature” forests appears to be effective in encouraging agricultural expansion on non-forest lands, finds a study published today in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

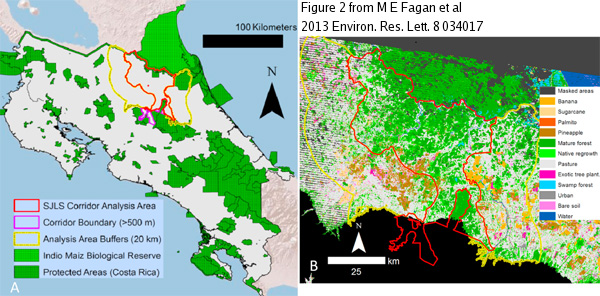

The research, which was led by Matthew Fagan of Columbia University, is based on analysis of satellite data calibrated with visits to field sites in the lowlands of northern Costa Rica.

The study found that since Costa Rica implemented its ban on conversion of mature forests in 1996, the annual rate of old-growth forest loss dropped 40 percent despite an agricultural boom in the region. The results suggest that Costa Rica is intensifying agricultural production while simultaneously sparing forests.

“We observed that following the ban, mature forest loss decreased from 2.2 percent to 1.2 percent per year, and the proportion of pineapple and other export-oriented cropland derived from mature forest declined from 16.4% to 1.9%,” the researchers write. “The post-ban expansion of pineapples and other crops largely replaced pasture, exotic and native tree plantations, and secondary forests.”

Fagan and colleagues observed that the ban seemed to be particularly effective at discouraging large-scale or industrial agriculture in mature forest areas. It was less successful in stopping conversion for cattle pasture.

“We conclude that forest protection efforts in northern Costa Rica have likely slowed mature forest loss and succeeded in re-directing expansion of cropland to areas outside mature forest,” they write. “Our results suggest that deforestation bans may protect mature forests better than older forest regrowth and may restrict clearing for large-scale crops more effectively than clearing for pasture.”

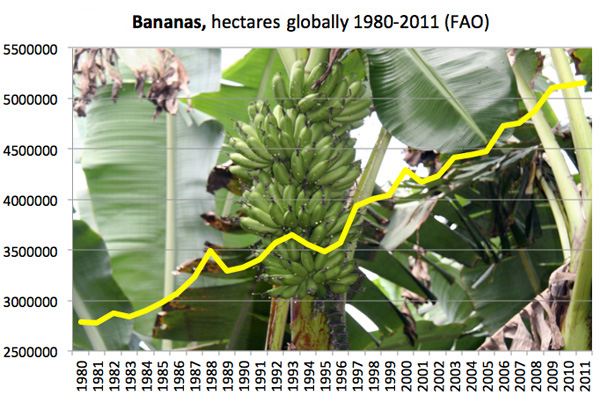

While those findings may seem counter-intuitive since large-scale crops are considerably more profitable than cattle ranching, they are consistent with trends emerging elsewhere. One possible explanation is industrial agricultural operations — chiefly pineapples and bananas in northern Costa Rica — require substantial capital investment, making the their owners less willing to risk easily-detectable illegality (satellite imagery is a useful law enforcement tool for large-scale land use). Furthermore, because their crops are destined for export markets, where environmental concerns and issues like traceability loom large, pineapple and banana growers avoid chopping down rainforests for farmland. In contrast, many cattle ranchers are relatively small operators, whose product is consumed locally, providing less of an incentive to respect the deforestation ban. Similar developments have been observed with soy and cattle production in parts of the Brazilian Amazon.

“The export-oriented banana and pineapple producers in northern Costa Rica may be more sensitive to potential boycotts and the tarnishing of their brands than smaller domestic cattle producers,” they write. “The success of the soy deforestation moratorium in Brazil shows that large producers can and do respond to socio-political pressures.”

Downsides to intensification

However the researchers suggest that intensification may not be an ecological panacea. They note that intensive agriculture has expanded into important non-protected forests, including wetlands and secondary forests. Additionally, industrial monocultures offer less habitat connectivity than less intensively managed landscapes — a typical cattle pasture includes scattered tree cover which is utilized by many species, whereas a pineapple farm is usually devoid of trees and functions as a biological desert. Finally the use of agricultural chemicals is a risk to animals and aquatic habitats.

“Pineapple and banana production in Costa Rica depends on extremely high applications of fertilizer and toxic pesticides,” the authors write. “In Costa Rica these agro-chemicals have degraded water quality and disrupted downstream ecosystems, and contaminated montane forests with pesticides.”

Nonetheless, from a land use policy perspective, the researchers conclude that Costa Rica’s approach may hold lessons for other areas where forests are being rapidly converted for agriculture.

“Comprehensive forest protection policies may be a potential tool to promote land-sparing in regions undergoing deforestation for intensive agriculture,” the write.

CITATION: M E Fagan et al (2013) Land cover dynamics following a deforestation ban in northern Costa Rica. Environ. Res. Lett. 8 034017