As if ocean acidification and climate change weren’t troubling enough (both of which are caused by still-rising carbon emissions), new research published in Nature finds that ocean acidification will eventually exacerbate global warming, further raising the Earth’s temperature.

Scientists have long known that tiny marine organisms—phytoplankton—are central to cooling the world by emitting an organic compound known as dimethylsulphide (DMS). DMS, which contains sulfur, enters the atmosphere and helps seed clouds, leading to a global cooling effect. In fact, in the past scientists have believed that climate change may actually increase DMS emissions, and offset some global warming, but they did not take into account the impact of acidification.

Researchers, headed by Katharina Six with the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, tested how acidification affects phytoplankton in the laboratory by lowering the pH (i.e. acidifying) in plankton-filled water tanks and measuring DMS emissions. When they set the ocean acidification levels for what is expected by 2100 (under a moderate greenhouse gas scenario) they found that cooling DMS emissions fell.

Plugging the results into global modeling system, Six says, “we get an extra warming of 0.23 to 0.48 degree Celsius from the proposed impact [by 2100],” adding that “less sulphur results in a warming of the Earth surface.” This creates a positive feedback loop that will likely have impacts that are anything but positive, according to scientists.

To date, the world has warmed approximately 0.8 degrees Celsius in the last century with a variety of impacts including worsening severe weather, rising sea levels, melting glaciers and sea ice, and imperiled species.

Six also notes that a warmer world does not necessarily mean a more productive world for phytoplankton as has been argued by researchers in the past.

“In former times it was assumed that phytoplankton potentially growth better in a warmer ocean,” she explained to mongabay.com. “However, the basis for plant growth is the supply with nutrients. As the oceans will stabilize in the warmer climate, fewer nutrients will be transported into the sunlight zone. Earth system models, like the MPI-ESM that was used for our study, project a decrease in primary production of 17 percent at the end of this century for a moderate climate scenario. The impact from climate change alone led to a decrease in DMS emission of 7 percent.”

The results are still preliminary as researchers have yet to test how DMS emissions will by impacted in tropical and subtropical waters, focusing to date on polar and temperate waters. In addition, further modeling should be done in order to understand possible uncertainties according to Six.

Still, the evidence is strong enough that the researchers write in the paper that “this potential climate impact mechanism of ocean acidification should be considered in projections of future climate change.” Essentially raising current estimates for a moderate climate scenario by around 10 percent.

Ocean acidification, which has been dubbed “climate change’s equally evil twin” by U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Jane Lubchenco, is expected to have largely negative impacts on many marine species, including dissolving the shells of crustaceans and molluscs, hampering coral reefs, and even changing how far fish can hear.

So, how do we stop this from happening?

“There is only one answer,” Katharina Six told mongabay.com, “the abatement of fossil fuel emissions.”

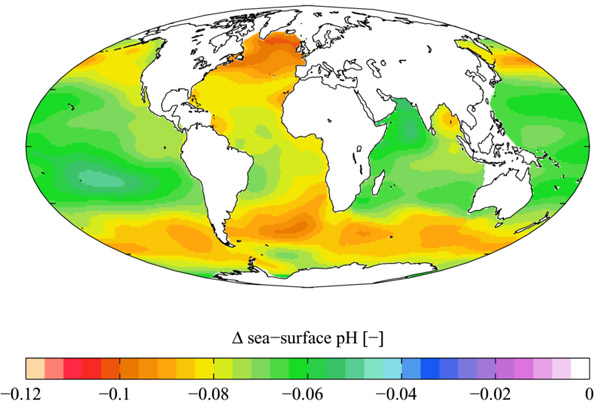

Changes in oceanic pH levels from 1700 to the 1990s. Image by: Plumbago/Creative Commons 3.0.

CITATION: Six, K. D., Kloster, S., Ilyina, T., Archer, S. D., Zhang, K. & Maier-Reimer, E. Global warming amplified by reduced sulphur

fluxes as a result of ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1981

Related articles

Ocean acidification pushing young oysters into ‘death race’

(06/11/2013) Scientists have long known that ocean acidification is leading to a decline in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) in the U.S.’s Pacific Northwest region, but a new study in the American Geophysical Union shows exactly how the change is undercutting populations of these economically-important molluscs. Caused by carbon dioxide emissions, ocean acidification changes the very chemistry of marine waters by lowering pH levels; this has a number consequences including decreasing the availability of calcium carbonate, which oysters and other molluscs use to build shells.

Animals dissolving due to carbon emissions

(12/03/2012) Marine snails, also known as sea butterflies, are dissolving in the Southern Seas due to anthropogenic carbon emissions, according to a new study in Nature GeoScience. Scientists have discovered that the snail’s shells are being corroded away as pH levels in the ocean drop due to carbon emissions, a phenomenon known as ocean acidification. The snails in question, Limacina helicina antarctica, play a vital role in the food chain, as prey for plankton, fish, birds, and even whales.

Threatened Galapagos coral may predict the future of reefs worldwide

(11/07/2012) The Galapagos Islands have been famous for a century and a half, but

even Charles Darwin thought the archipelago’s list of living wonders

didn’t include coral reefs. It took until the 1970s before scientists

realized the islands did in fact have coral, but in 1983, the year the

first major report on Galapagos reef formation was published, they

were almost obliterated by El Niño. This summer, a major coral survey

found that some of the islands’ coral communities are showing

promising signs of recovery. Their struggle to survive may tell us

what is in store for the rest of the world, where almost

three-quarters of corals are predicted to suffer long-term damage by

2030.

Coral calcification rates fall 44% on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

(09/04/2012) Calcification rates by reef-building coral communities on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef have slowed by nearly half over the past 40 years, a sign that the world’s coral reefs are facing a grave range of threats, reports a new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research – Biogeosciences.

Earth’s ecosystems still soaking up half of human carbon emissions

(08/06/2012) Even as humans emit ever more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, Earth’s ecosystems are still sequestering about half, according to new research in Nature. The study finds that the planet’s oceans, forests, and other vegetation have stepped into overdrive to deal with the influx of carbon emitted from burning fossil fuels, but notes that this doesn’t come without a price, including the acidification of the oceans.

2,600 scientists: climate change killing the world’s coral reefs

(07/10/2012) In an unprecedented show of concern, 2,600 (and rising) of the world’s top marine scientists have released a Consensus Statement on Climate Change and Coral Reefs that raises alarm bells about the state of the world’s reefs as they are pummeled by rising temperatures and ocean acidification, both caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The statement was released at the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium.