What happens to animals when their forest is cut down? If they can, they migrate to different forests. But in an age when forests are falling far and fast, many species may have to shift to entirely different environments. A new paper in Folia Primatologica theorizes that some 60 primate species and 20 wild cat species in Asia and Africa may be relying more on less-impacted environments such as swamp forests, mangroves, and peat forests.

“Where primates and felids face forest habitat disturbance, they may need to shift habitats, diets, activity patterns,” author of the paper Katarzyna Nowak with Princeton University told mongabay.com. “In areas with swamp forests—like areas with hard to reach mountaintops—these taxa can find safety and shelter in the flooded forest, which may be less disturbed than the adjacent upland forest.”

However, such areas have often been neglected by conservationists, in part due to the difficult terrain, but also because such environments are not usually considered prime habitat for most primates and cats. But remarkable discoveries have already been made: in 2006 the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) discovered 125,000 lowland gorillas living in a swamp forest in Lake Télé in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Nowak argues that more surveys are needed in these often-overlooked ecosystems.

Peat swamp in Borneo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

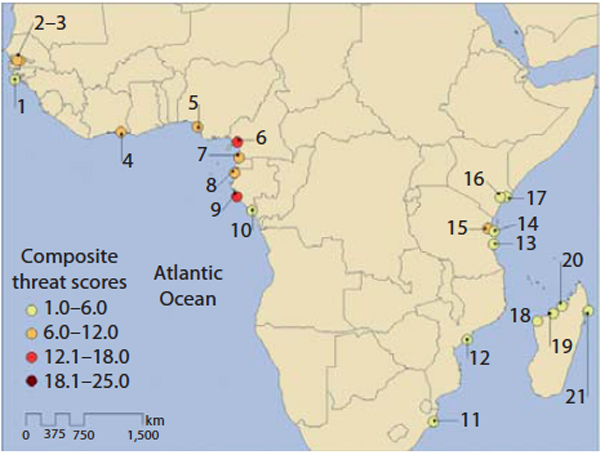

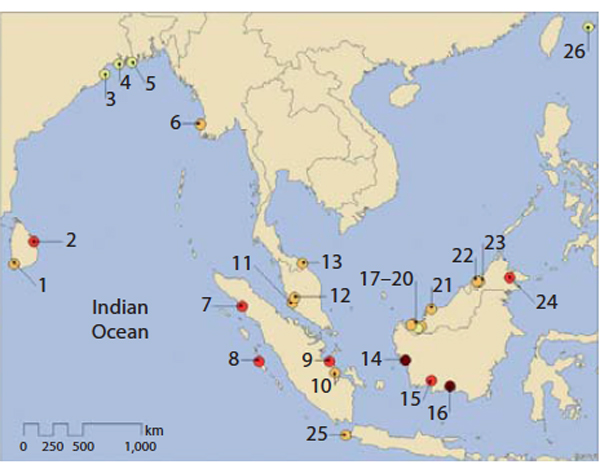

In her paper, she identifies 47 possible sites across Africa and Asia where primates and cats may be taking refuge, including 21 sites in Africa and 26 sites in Asia.

“For primates, Petit Loango in Gabon is certainly a prime mangrove forest site where most of the resident species exploit mangroves,” she says. “We could certainly conduct a more detailed behavioral study of mangrove use here. Less known populations of primates and felids may be found in mangroves of Rio Ntem o Campo in Equatorial Guinea, and Conkouati-Douli National Park in Congo.”

In Asia, the paper points to Gunung Palung National Park in Sumatra and Sebangau National Park in Borneo as prime spots supporting primate and felid species.

She recommends that conservation groups “survey and prioritize key mangrove sites, and take action, for example extend beekeeping cooperatives and nature tourism to mangrove areas, but also understand traditional stewardship practices.”

Aside from likely extending refuge to some mammals, these lesser-known forests provide a wealth of ecosystem services. For example, mangroves are known as key fish nurseries, important carbon sequesters, and buffers against tropical storm damage. Despite their huge importance, less than 10 percent of mangroves worldwide are protected and mangroves are vanishing at incredible rates: around 35 percent of the world’s mangroves were lost in just twenty years (1990 to 2010). There has also been rising concern over the loss of peat and swamp forests as well, especially due to carbon emissions and biodiversity decline.

Captive Asian fishing cat. The Asian fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

“We must extend our protection of forests to flooded forests, especially mangroves. These may still be less threatened than freshwater swamp forests because of their low nutrient levels and impenetrability. The value of mangroves as important wildlife areas needs to be fully assessed, while mangrove-oriented nature tourism such as wildlife viewing trips in traditional dung-out canoes could help encourage mangrove restoration and even ‘mangrove plantations’ for honey and carbon credits,” says Nowak who also points out that “mangrove reserves are often un-named, designated simply as ‘mangrove forest reserves’ unlike terrestrial protected areas which have distinct names, identities and are immediately recognized.”

Now is the time to start surveying and protecting these “relatively neglected” ecosystems, argues Nowak, who points to new technologies such as remote camera traps that could give scientists an inside look at life in the world’s extreme forests.

From paper: “Twenty-one Afrotropical mangroves, 25 Indo-Malayan mangroves and peat swamp forests,

and 1 Japanese mangrove site important for primates and felids. R = Ramsar Site; A = adjacent

to or part of a Ramsar Site; C = Critically Endangered species present. Aftrotropical sites:

1 = Bijagos Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau (score = 4.5; species n = 3); 2 = River Gambia National

Park, Gambia (8.5; 5); 3 = Saloum Delta (R), Senegal (7; 5); 4 = Ebrie Lagoon, Côte d’Ivoire (7;

4); 5 = Apoi Creek Forests (R, C), Niger Delta, Nigeria (8; 4); 6 = Douala-Edea Reserve (C), Cameroon

(13; 8); 7 = Rio Ntem o Campo (R, C), Equatorial Guinea (12; 7); 8 = Gabon Estuary (C),

Gabon (9.5; 7); 9 = Petit Loango (R, C) (13.5; 8); 10 = Conkouati-Douli National Park (R), Congo

(6; 4); 11 = St. Lucia System (R), South Africa (5.5; 4); 12 = Zambezi River Delta (A), Mozambique

(4.5; 4); 13 = Rufiji Delta (A), Tanzania (5.5; 5); 14 = Jozani-Pete-Uzi Island mangroves,

Zanzibar (5.5; 4); 15 = Saadani National Park (6.5; 6); 16 = Tana River Delta, Kenya (3.5; 3);

17 = Lamu Island Archipelago (4; 3); 18 = Besalampy, Madagascar (1; 1); 19 = Bombetoka Bay

(2.5; 1); 20 = Anjajavy Reserve (2.5; 1); 21 = Masoala National Park (1.5; 1).” Map by: Nowak.

From paper: “Twenty-one Afrotropical mangroves, 25 Indo-Malayan mangroves and peat swamp forests,

and 1 Japanese mangrove site important for primates and felids. R = Ramsar Site; A = adjacent

to or part of a Ramsar Site; C = Critically Endangered species present. Indo-Malayan sites:

1 = Maduganga (R), Sri Lanka (8.5; 4); 2 = Mahaweli Ganga (13; 6); 3 = Bhitarkanika mangroves

(R), India (3; 3); 4 = Sundarbans, India (5.5; 4); 5 = Sundarbans (R), Bangladesh (5.5; 4); 6 = Irrawaddy

Delta, Myanmar (8; 4); 7 = Suaq Balimbing (C), Indonesia (13.5; 6); 8 = Mentawai Islands

(C) (13; 5); 9 = Berbak GR (R, C) (17; 9); 10 = Banyuasin Musi River Delta (C) (8.5; 5);

11 = Kuala Selangor mangroves, Malaysia (10; 6); 12 = North Selangor swamp (C) (10.5; 5); 13 =

Pa Phru To Daeng, Thailand (9.5; 5); 14 = Gunung Palung National Park, Indonesia (25; 13);

15 = Tanjung Puting National Park (17.5; 10); 16 = Sebangau National Park (24.5; 13); 17 = Kuching

Wetlands National Park (R), Malaysia (7.5; 4); 18 = Bako National Park (11.5; 6); 19 = Sadong

Swamp Forest (6; 3); 20 = Maludam National Park (C) (10.5; 5); 21 = Pulau Bruit Rajang

Delta (8; 5); 22 = Trusan Sundar mangroves (10; 5); 23 = Lawas mangroves (10; 5); 24 = Sandakan

Tambisan Wetlands (14; 7); 25 = Ujung Kulon National Park, Indonesia (7; 4); 26 =

Iriomote Island Forest Ecosystem Reserve (C), Japan (3; 1).” Map by: Nowak.

CITATION: Nowak, Katarzyna. 2013. Mangrove and Peat Swamp Forests: Refuge Habitats for Primates and Felids. Folia Primatologica. Vol. 83, no. 3–6, pp. 361–76.

Related articles

Drill baby drill! The fate of African biodiversity and the monkey you’ve never heard of

(05/02/2013) Equatorial Guinea is not a country that stands very large in the American consciousness. In fact most Americans think you mean Papua New Guinea when you mention it or are simply baffled. When I left for Bioko Island in Equatorial Guinea, I also knew almost nothing about the island, the nation, or the Bioko drills (Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis). The subspecies of drill is unique to Bioko Island and encountering them was an equally unique experience. I initially went to Bioko as a turtle research assistant but ended up falling in love with the entire ecosystem, especially the Bioko drills as I tagged along with drill researchers.

13 year search for Taiwan’s top predator comes up empty-handed

(05/01/2013) After 13 years of searching for the Formosan clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa brachyura), once hopeful scientists say they believe the cat is likely extinct. For more than a decade scientists set up over 1,500 camera traps and scent traps in the mountains of Taiwan where they believed the cat may still be hiding out, only to find nothing.

Malaysia may be home to more Asian tapirs than previously thought (photos)

(04/23/2013) You can’t mistake an Asian tapir for anything else: for one thing, it’s the only tapir on the continent; for another, it’s distinct black-and-white blocky markings distinguishes it from any other tapir (or large mammal) on Earth. But still little is known about the Asian tapir (Tapirus indicus), including the number surviving. However, researchers in Malaysia are working to change that: a new study for the first time estimates population density for the neglected megafauna, while another predicts where populations may still be hiding in peninsular Malaysia, including selectively-logged areas.

Illegal logging threatens lowland forests in Indonesian national park

(04/16/2013) Illegal logging in the heart of Indonesia’s Gunung Palung National Park may be putting one of the country’s last remaining lowland forests at risk. The park, located in Indonesia’s West Kalimantan province on the island of Borneo, is home to a number of endangered species including hornbills and gibbons, as well as around 2,500 orangutans, and is the site of a research station that has been collecting data on the forest for more than 20 years.

Future generations to pay for our mistakes: biodiversity loss doesn’t appear for decades

(04/15/2013) The biodiversity of Europe today is largely linked to environmental conditions decades ago, according to a new large-scale study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Looking at various social and economic conditions from the last hundred years, scientists found that today’s European species were closely aligned to environmental impacts on the continent from 1900 and 1950 instead of more recent times. The findings imply that scientists may be underestimating the total decline in global biodiversity, while future generations will inherit a natural world of our making.

How many animals do we need to keep extinction at bay?

(04/15/2013) How many animal individuals are needed to ensure a species isn’t doomed to extinction even with our best conservation efforts? While no one knows exactly, scientists have created complex models to attempt an answer. They call this important threshold the “minimum viable population” and have spilled plenty of ink trying to decipher estimates, many of which fall in the thousands. However, a new study in Conservation Biology shows that some long-lived animals may not need so many individuals to retain a stable population.

Will Indonesia renew its moratorium on new forest conversion licenses?

(04/12/2013) Indonesia’s forestry minister has again said that the country will extend its two-year moratorium on primary forest and peatland conversion, which is set to expire next month.

Fighting deforestation—and corruption—in Indonesia

(04/11/2013) The basic premise of the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) program seems simple: rich nations pay tropical countries for preserving their forests. Yet the program has made relatively limited progress on the ground since 2007, when the concept got tentative go-ahead during U.N. climate talks in Bali. The reasons for the stagnation are myriad, but despite the simplicity of the idea, implementing REDD+ is extraordinarily complex. Still the last few years have provided lessons for new pilot projects by testing what does and doesn’t work. Today a number of countries have REDD+ projects, some of which are even generating carbon credits in voluntary markets. By supporting credibly certified projects, companies and individuals can claim to “offset” their emissions by keeping forests standing. However one of the countries expected to benefit most from REDD+ has been largely on the sidelines. Indonesia’s REDD+ program has been held up by numerous factors, but perhaps the biggest challenge for REDD+ in Indonesia is corruption.