The sight of a clownfish wriggling through the stinging tentacles of its anemone is a familiar and seemingly well-understood one to most people—the stinging anemone provides a protective home for the clownfish who is immune to such stings, and in turn the clownfish chases away any polyp-eating sunfish eyeing the anemone’s tentacles for a meal. But recent research has shown that all that clownfish wriggling significantly helps to oxygenate the anemone at night, when oxygen levels in the water are low.

“Anemones are not only sedentary but also lack the ability to self modulate the water flow over their tissues,” says Joseph Szczebak lead author of the paper in the Journal of Experimental Biology. “As such, they are particularly prone to succumbing to low oxygen conditions. By aerating their host anemones, anemonefish [i.e. clownfish] ensure their hosts have a constant supply of oxygen-rich water.”

This behavior is a prime example of the symbiotic relationships that are a hallmark of life in the coral reef ecosystem the clownfish and anemone call home, in which one species helps another satisfy a need it would have trouble fulfilling alone in exchange for help of a similar kind. The clownfish and anemone are almost quite literally scratching each others’ back, albeit with perhaps a softer, more snuggly touch that leads to easier breathing.

Clownfish taking shelter in an anemone. Photo by: Joseph Szczebak. |

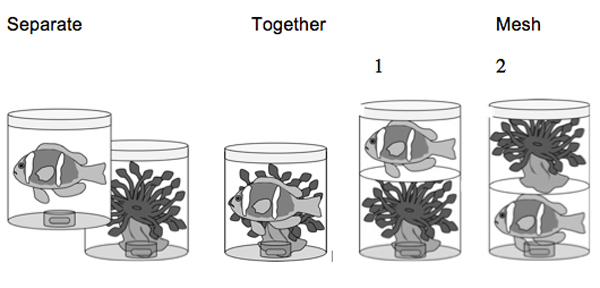

For their experiment, Szczebak and his Auburn University colleagues observed the nocturnal behavior of the clownfish—also known as the anemonefish—in several ways: when it was with the anemone, when it was completely separated from the anemone, and when it was only separated from the anemone by a mesh screen, allowing the animals to be aware of the others’ presence.

There were two mesh variations (pictured below)—including one with the water flow passing by the anemone first, and the other with the flow passing by the clownfish first—which were included to see whether simply the sight or smell of each other had any effect on behavior and oxygen uptake. “Sea anemone chemical compounds” have been observed to “directly influence the recruitment and recognition behaviors of anemonefishes toward host sea anemones,” noted Szczebak to mongabay.com of previous scientific literature, but “the extent to which sea anemone chemical cues influence anemonefish behavior at night has yet to be discerned.”

The researchers found that though the smell of the anemone did result in more “switching” behavior from the clownfish, it was only when the two were together and able to make physical contact—the clownfish “wedging” deep into the anemone, “switching” directions abruptly, and “fanning” its fins—that oxygen uptake significantly increased. In addition, this behavior was far less frequent when the clownfish was not with the anemone.

The study sheds much light on the pair’s interactions at night, for which few studies exist despite more than a century of research on their relationship, as well as nighttime being when clownfish actually spend the most time nestled in their anemones. Yet Szczebak maintains that there is still much to be discovered regarding the complexity of these symbiotic interactions. Only in 2009 did a study reveal that clownfish waste provides essential nutrients for their anemone hosts.

“It is still unclear if flow modulation is the intended effect of these nocturnal antics,” says Szczebak, noting that the clownfish’s behavior could serve an alternative or additional purpose, such as clearing debris from the anemone, and researchers at Auburn University are conducting further, similar studies to this end. Regardless, Szczebak and his colleagues’ findings provide valuable insight into life on one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on our planet still full of mystery.

Clownfish and anemone. Photo by: Joseph Szczebak.

From Szczebak et al: ‘Flow-through respirometry treatments to assess the effects of symbiotic interactions on the dark oxygen uptake (VO2) of two-band anemonefish (A. bicinctus) and bulb-tentacle sea anemones (E. quadricolor). Mesh subtreatments, mesh1 (1) and mesh2 (2), are depicted. Respirometry chambers were constructed from 6.35-mm-thick acrylic cylinders (inner diameter, 16.5 cm) with a volume of either 2.5 or 3.5 l (depending on animal sizes).’

CITATION: Szczebak, J. T., Henry, R. P., Al-Horani, F. A. and Chadwick, N. E. (2013). Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 970-976.

Related articles

Western scrub jay funerals…what’s all the ruckus?

(12/10/2012) The western scrub jay (Aphelocoma californica) is a common denizen of suburban neighborhoods in the U.S., loitering at bird feeders and amusing bird watchers with their entertaining antics. Known to birders as ‘WESJ,’ this handsome bird is non-migratory and territorial during the breeding season, but what’s curious about WESJ’s is the way they respond to risks in their environment. When descended on by a predator or encountering a dead member of its kind, these birds hop from perch to perch and call loudly, ensuing in a ‘cacophonous reaction,’ a term coined by researchers at the University of California, Davis who are studying the behavior of these unique birds.

Despite small brains, gray mouse lemurs use calls to avoid inbreeding

(12/03/2012) As a small-brained and largely solitary primate, the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) wasn’t supposed to have the capacity to distinguish the calls of its kin calls from other lemurs. However, a new study in BMC Ecology, finds that a female gray mouse lemur is able to determine the mating calls of its father, allowing it avoid inbreeding. The discovery challenges the long-held belief that only large-brained, highly social animal are capable of determining kin from calls.

Endangered muriqui monkeys in Brazil full of surprises

(11/26/2012) On paper, the northern muriquis (Brachyteles hypoxanthus) look like a conservation comeback story. Three decades ago, only 60 of the gentle, tree-dwelling primates lived in a fragment of the Atlantic Forest along the eastern coast of Brazil. Now there are more than 300. But numbers don’t tell the whole story, according to anthropologist Karen Strier and theoretical ecologist Anthony Ives of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The pair analyzed 28 years of data on the demographics of the muriquis, one of the longest studies of its kind. They found surprising patterns about birth and death rates, sex ratios, and even how often the monkeys venture out of their trees. These findings raise questions about the muriquis’ long-term survival and how best to protect them, the scientists wrote in the Sept 17 issue of PLoS ONE.

Great apes suffer mid-life crisis too

(11/19/2012) Homo sapiens are not alone in experiencing a dip in happiness during middle age (often referred to as a mid-life crisis) since great apes suffer the same according to new research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). A new study of over 500 great apes (336 chimpanzees and 172 orangutans) found that well-being patterns in primates are similar to those experience by humans. This doesn’t mean that middle age apes seek out the sportiest trees or hit-on younger apes inappropriately, but rather that their well-being starts high in youth, dips in middle age, and rises again in old age.

Clever crows may grasp hidden causes

(11/15/2012) Crows may be imagining more than we imagined. New research suggests certain crows make decisions based on factors they can’t see. A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) deepens our understanding of these crafty corvids, and could help explain how human reasoning evolved. Crows are intelligent problem solvers, capable of making hook-shaped tools to retrieve food and using multiple tools in a logical sequence. New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides) are particularly adept tool users, and have often been the subject of cognitive research. In this study, the New Zealand–based researchers tested whether New Caledonian crows could trace an event back to a cause that was hidden from their view.

New species of bioluminescent cockroach possibly already extinct by volcanic eruption

(11/14/2012) While new species are discovered every day, Peter Vršanský and company’s discovery of a light-producing cockroach, Lucihormetica luckae, in Ecuador is remarkable for many reasons, not the least that it may already be extinct. The new species represents the only known case of mimicry by bioluminescence in a land animal. Like a venomless king snake beating its tail to copy the unmistakable warning of a rattlesnake, Lucihormetica luckae’s bioluminescent patterns are nearly identical to the poisonous click beetle, with which it shares (or shared) its habitat.