Mongabay.com is partnering with the Skoll Foundation ahead of the Skoll World Forum on Social Entrepreneurship to bring a series of perspectives that aim to answer the question: how do we feed the world and still address the drivers of deforestation?

|

HOW DO WE FEED THE WORLD AND STILL ADDRESS THE DRIVERS OF DEFORESTATION? Soy, cattle, rice, palm oil, and logging are the principal drivers of deforestation. As global population increases from 7 billion to 9 billion by 2040, and as more and more people around the world rise out of poverty into the middle class, the demand for these commodities and practices will continue to rise with them. To address these issues, and in advance of the World Forests Summit hosted by the Economist in March, the Skoll World Forum on Social Entrepreneurship partnered with the Stanford Institute for the Environment and Mongabay News to surface the latest insights and innovations at the intersection of deforestation and sustainability. This debate will also set the stage for a larger discussion on deforestation at this year’s Skoll World Forum in Oxford, UK. |

A few weeks ago the Skoll World Forum hosted an online debate on how increased global consumption can be balanced with sustainability. The debate asks how a rapidly growing world that is ever consuming can hope to feed everyone, and at the same time address the deforestation that is emitting massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and destroying the world’s greatest tropical forests. Many contributors made very strong points—even contradicting one another in their approaches and ideas.

The question is daunting, and can seem both overwhelming and discouraging if one thinks about how rapidly the world population is increasing, destined to reach 9 billion by 2050. The question becomes even more challenging when one considers the massive numbers of people entering the lower middle classes, for example in China and India, and their ever increasing consumption patterns including more and more meat, a major driver of deforestation. Imagine a doubling of the world’s population coupled with a doubling of the world’s consumption: two times two equals four. Can we really consume four times more and still destroy less tropical forests?

David Rothschild Principal, Skoll Foundation Portfolio Team As a Principal of the Skoll Foundation’s Portfolio Team, David Rothschild manages a variety of key relationships with funded social entrepreneurs, domain experts, policy makers, corporate partners and co-funders. David develops and structures funding opportunities to drive large scale change in the focus areas of the foundation. |

I will start by saying I am not a pessimistic person. I have been working on tropical forest issues for over 20 years, and I have never been as optimistic about the plight of the world’s tropical forests as I am today. Just 10 years ago, deforestation seemed out of control. Billions of dollars was being spent to save the world’s tropical forests, and yet their destruction increased every year. In 2003 and 2004, the years when Amazon deforestation rates peaked, I was living in the Bolivian Amazon along the border with Brazil. There were entire weeks when the sun seemed to be struggling to burn through a constant haze of smoke from the seemingly endless forest burning. Despite this, those of us working to save tropical forests made a few gains. But back then, even as gains were made, deforestation continued. Indigenous peoples gained more rights to their lands. Deforestation continued. Protected areas and biodiversity hot spots were set aside for protection. Deforestation increased.

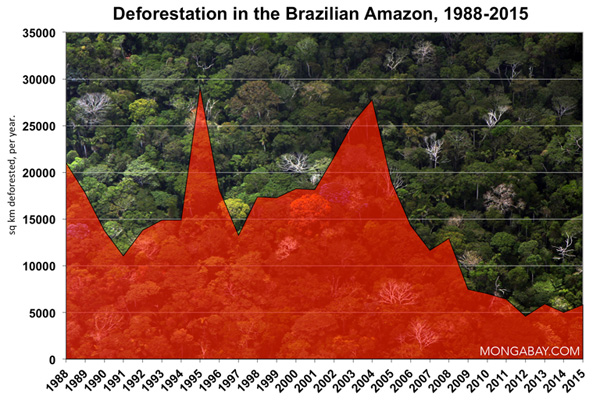

But something has changed since those times. Today, in the two places responsible for the vast majority of the world’s tropical deforestation—Brazil and Indonesia—we see a path to success. Deforestation is no longer out of control. The problem is not solved—far from it—but it is clear what needs to be done, we have momentum in the right direction, and pressure continues to move us forward. In fact, Brazil’s deforestation, previously responsible for about a third of the world’s forest carbon emissions, has been reduced to 70 percent below 2005 levels. This has resulted in over 2 billion tons of carbon not being released into the atmosphere, and is now the single greatest reduction in carbon emissions attributable to humankind. Let’s repeat that last point— by bringing deforestation somewhat under control, Brazil has achieved the greatest reduction in carbon emissions ever attributable to humankind—over 2 billion tons. This issue clearly deserves more attention. There are real gains to be made in the effort to reduce carbon emissions. With a global focus on the Amazon, Indonesia and central Africa, there are a lot of reachable victories to be had in the coming decade to bring deforestation under control and make an even larger contribution to slowing climate change.

Annual deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon

So how do we feed the world and control tropical deforestation? Contributors to the recent Skoll World Forum online debate point the way. We need:

- Strong leadership from the private sector to increase agricultural productivity without deforesting more land ( yes, it’s do-able!)

- Improved governance and enforcement of environmental regulations in tropical forest countries. This includes increased effectiveness of command and control measures and protected areas, as well as increased recognition of land rights of indigenous peoples

- Increased value for standing forest

Jason Clay of the World Wildlife Fund points out that expansion of the agricultural frontier accounts for up to 90 percent of global deforestation each year. This is one of the most important points that should guide actions on addressing tropical deforestation for years to come. We need to engage the agriculture sector! Agriculture needs to be part of the solution—there is no other way to address deforestation. As Jason Clay says, “As environmentalists, if we don’t change where and how we produce food and fiber, we can turn the lights off and go home.”

Jeffrey Horowitz of Avoided Deforestation Partners points to the Consumer Goods Forum, made up of over 400 companies that have committed that their agricultural-based supply lines will become sustainable and deforestation-free by 2020. This group includes such industry movers as Cargill, Unilever, Wal-Mart and General Mills. This is a huge step forward, and a significant part of the solution—but we can’t lose sight of the worst performing 25 percent of producers (thank you Jason Clay). And we need to push companies both from the supply side and the demand side. Recently Oxfam America launched its Behind the Brands campaign—taking on major food corporations. Oxfam ranked the ten largest food and beverage companies on a range of social and environmental issues and is pushing consumers and the public to get involved.

So that takes us to the second piece of the solution: increased governance of enforcement of environmental regulations. As I said earlier, we can see a path forward, and there are examples that are working. In Brazil, deforestation rates are at levels we never dreamed of just 5 years ago. Beto Verissimo of Imazon shares how in the State of Para increased governance and enforcement of environmental regulations is being taken to the local level. It is one thing to increase federal governance and controls, but in the State of Para, the Green Municipalities Program is bringing increased governance to the state, municipal and even individual landowner level. The State of Para historically has been one of Brazil’s two major poles of deforestation, as well as Brazil’s center for other social ills like organized crime and slavery. Put simply, Para used to be a poster child for lack of governance. Today, almost all of Para’s rural municipalities (similar to counties), have signed up for the Green Municipalities Program, committing to controlling deforestation and transforming their rural economies to sustainable production. The program is also helping rural producers increase productivity on less land. This commitment includes registering rural landowners’ properties with the state. The program is bringing regulation and planned production to a region that only a few years ago, at times, seemed ruled more by thugs and organized crime than by government.

Conversion of lowland rainforest in Borneo for palm oil production.

But bringing governance and control is more than just rules, regulations and organized production. It also means education and planning for a sustainable future with livelihoods that support it. Andrea Margit of the Roberto Marinho Foundation points out that it is folly to expect a forest population educated with urban education materials to graduate ready to engage in a sustainable forest economy. In Brazil, a forest education movement is preparing the next generation of forest workers to be educated with the tools needed for sustainable forest production.

That brings us to our third piece of the solution: bringing value to the standing forest. This last goal may prove more difficult than the other two, which might have seemed unexpected only a few years ago. This may be one of the toughest pieces of the puzzle, and the other pieces aren’t easy. As Frank Merry notes, if we want to conserve forests held in private lands, we have to make it a valuable commodity that farmers will take into consideration when making economic decisions about how to use their lands. This isn’t easy considering agricultural land can be 10 times more valuable than forest. The good news is there has been a global commitment to bring value to standing forests. The bad news is that the mechanisms to do so are complicated, and the vast majority of farmers in tropical forest areas have yet to see any benefit for leaving their forest standing.

Governments have pledged over $7 billion towards bringing value to standing forest through the global initiative called REDD+—reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. REDD+ looks to bring both government and private funding to support projects that reduce forest emissions, eventually leading to a market where tropical forest emissions reductions can be traded. One would think REDD’s already massive funding would have brought value to standing forest across the globe. So far it has not.

Michael Jenkins of Forest Trends highlights the critical need to deploy REDD funds more efficiently and to increase REDD funding. While over $7 billion of REDD funds have been committed, the unfortunate reality is that only a tiny fraction of government funds have made their way to projects that actually reduce deforestation. Way too many REDD committed funds are either not dispersed or caught up in bureaucracy. Despite this lag, REDD is a fabulous opportunity to bring significant funding to projects that reduce deforestation around the globe, and we should not let naysayers and bureaucracy allow this window of opportunity to pass us by.

Selective logging operation in Malaysia

There is still much to be excited about. Each year there are more REDD project experiences to draw from. As Steve Schwartzman points out, low carbon agriculture and the restoration of degraded lands can help to be sure that reductions in deforestation do not simply shift production elsewhere. The world’s growing number of carbon markets can help, including markets developing in California, Australia, Canadian provinces, Australia, South Korea and potentially Brazil. While some may criticize REDD as a way for big polluters to continue emitting carbon, as long as tropical states or countries show they’ve made their reduction targets with robust remote sensing and field-based mechanisms, the reduction in carbon emissions will have actually happened. And let’s not forget that so far the greatest reduction in carbon emissions attributable to humankind is from reducing deforestation. So let’s all continue to pressure our governments and multilateral agencies to focus on reducing global deforestation through our global governance systems.

As I said above, I am optimistic about the future of the world’s tropical forests. Brazil continues to bring its deforestation rate down, and still has a lot of work to do, especially considering a major setback recently with changes to its legislation about private use of forested lands. Indonesia remains years behind Brazil, but still looks promising. New funds from Norway provide a strong carrot, based on a payment for performance system to reduce deforestation similar to the Amazon Fund in Brazil. In a dramatic turnaround, Asia Pulp and Paper, the world’s third largest paper supplier, announced that it would end its involvement with rainforest deforestation in Indonesia. If Asia Pulp and Paper carries out its commitment, others could follow suit in Indonesia. Coupled with the right incentives, it might even lead to broader forestry sector reform.

In sum, I remain cautiously hopeful. With continuing international support and pressure, private sector companies responsible for driving tropical deforestation can lead the way, tropical forest countries can build governance, and the international community can create markets and systems to bring value to standing forest. And hence we as a global community may be blessed to pass on our tropical forests, with their biological and cultural diversity, and their capacity to supply global demand for tropical forest commodities, to our future generations.

Borneo rainforest

To discuss this commentary, please visit Debate on food security and deforestation becomes a global call to action

|

ALL POSTS IN THIS SERIES

6 lessons for stopping deforestation on the frontier (04/09/2013) In 1984, at the tail end of the Brazilian dictatorship, I took up residence in a frontier town called Paragominas in the eastern Amazon. I went to study rainforests and pasture restoration, but soon became captivated as well by the drama of the frontier itself. Forests were hotly contested among cattle ranchers, smallholder communities, land speculators and more than a hundred logging companies, sometimes with fatal results. If we are to meet rising global demand for food, conserve tropical forests, and mitigate climate change at the pace that is necessary, we must become much better at taming aggressive, lawless tropical forest frontiers where people are making a lot of money cutting forests down. Can we meet rising food demand and save forests? (04/03/2013) A few weeks ago the Skoll World Forum hosted an online debate on how increased global consumption can be balanced with sustainability. The debate asks how a rapidly growing world that is ever consuming can hope to feed everyone, and at the same time address the deforestation that is emitting massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and destroying the world’s greatest tropical forests. Many contributors made very strong points—even contradicting one another in their approaches and ideas. Strong ‘no deforestation’ commitments save forests and feed people (03/12/2013) As a global community, we have so far failed to answer this most pressing question; we have yet to build our cloud. Deforestation rates are down in some places, but overall, our forests continue to disappear much as they have for the past 50 years, driven principally by increasing global demand for food. Can we feed the world and save our forests? Yes, we can, and the solution lies in the global supply chain and the message some companies are now sending their suppliers: ‘If you cut down trees, I won’t buy your product.’ This has the power to silence bulldozers. It’s already doing so and now it’s time to go to scale. The need to jump-start REDD to save forests (03/08/2013) At least US$7.3 billion has been pledged for REDD+ over the period from 2008 to 2015, with $4.3 billion pledged for REDD+ readiness during the fast-start period alone (2010-2012). In addition to these funds, private investors, private foundations, and others have been channeling financial support to developing countries for REDD+ and related programs for several years now. A promising initiative to address deforestation in Brazil at the local level (03/05/2013) The history of the Brazilian Amazon has long been marked by deforestation and degradation. Until recently the situation has been considered out of control. Then, in 2004, the Brazilian government launched an ambitious program to combat deforestation. Public pressure—both national and international—was one of the reasons that motivated the government to act. Another reason was that in 2004, deforestation contributed to more than 55 percent of Brazil’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making Brazil the fourth-largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world. Saving forests by putting a price on them (03/04/2013) During the 2013 SuperBowl, the championship game of the US National Football League, a truck company aired an advertisement that likened farmers to God’s favorite assistant. It suggested that when God needs something tough, or gentle, done, he calls a farmer. The narration, taken from a speech given to the Future Farmers of America in 1978 by Paul Harvey, a radio host, plays directly to the near mythical stature of farmers and ranchers in American culture and their deep connection to nature. Saving forests by stemming agricultural sprawl (03/01/2013) I’m fortunate to travel the world helping conserve habitats for some of the world’s most iconic species. When I visit places like the Amazon and Sumatra, I’m still awestruck by their diversity and pristine beauty. I’m also reminded how threatened they are. Our growing demand for food and fiber is fueling deforestation in resource-rich regions of the world. As environmentalists, if we don’t change where and how we produce food and fiber, we can turn off the lights and go home. There won’t be any biodiversity left to protect. Can saving forests help feed the world? (02/28/2013) As world population climbs from 7 to a projected 9 billion people and emerging and developing economies demand ever more of the food and fiber that drive deforestation, many environmentalists ask with increasing urgency whether and how tropical forests can survive. But the question may actually be whether and how the world’s increasing, and increasingly rich, population can be fed unless tropical forests survive. The challenge of putting Brazil’s forests in good hands (02/28/2013) People often associate Brazil with its forests. It’s no wonder given that nearly 60% of the country’s territory is covered by forest and it holds about one-third of the world’s remaining tropical rainforests. You might assume that a country like this would care about educating people to sustainably manage this precious heritage. Well, you’d be wrong! The corporate conservation revolution (02/27/2013) There’s a new kind of environmental hero emerging. They don’t live in Washington, D.C., and they’re known more for their interest in increasing earnings than in reducing greenhouse gases. They are found in an unlikely place: The Corporate Boardroom, and they’re making a big difference in saving the worlds forests and our climate. In recent years, a group of visionary corporate leaders have been quietly teaming up with a growing number of environmental groups to take a hard look at what’s left of our planet’s natural resources. Together, they agree: we are past the point where our land and oceans can meet the food, energy and commodity demands of our planet’s seven billion inhabitants. |

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in this op-ed do not necessarily reflect the views of Mongabay.com or its staff. Mongabay founder, president, and editor Rhett A. Butler served as an advisor to the Skoll Foundation from 2010-2012.

Related articles