- 2012 was another year of mixed news for the world’s tropical forests.

- This is a look at some of the most significant tropical rainforest-related news stories for 2012.

- There were many other important stories in 2012 and some were undoubtedly overlooked in this review.

- If you feel there’s something we missed, please feel free to highlight it in the comments section. Also please note that this post focuses only on tropical forests.

Rainforest in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

2012 was another year of mixed news for the world’s tropical forests. This is a look at some of the most significant tropical rainforest-related news stories for 2012.

There were many other important stories in 2012 and some were undoubtedly overlooked in this review. If you feel there’s something we missed, please feel free to highlight it in the comments section.

Also please note that this post focuses only on tropical forests.

Science on the impacts of deforestation and the effects of climate change on forests

Research published in 2012 provided a better understanding of tropical deforestation’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. Two studies — one published in Science and the other published in Nature Climate Change, concluded that while deforestation now accounts for a lower share of global emissions relative to the late 1990s, it still represents roughly 10 percent of gross emissions. Estimates of emissions from deforestation, forest fires, and peatlands degradation remain highly contentious.

Several papers published in 2012 raised disturbing questions about the health of tropical forests worldwide. In January, a review published in Nature warned that deforestation, forest degradation, and the effects of climate change are weakening the resilience of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, potentially leading to loss of carbon storage and changes in rainfall patterns and river discharge. That warning was echoed by a December Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study that found the effects of the massive 2005 Amazon drought persisted longer than previously believed, raising questions about the world’s largest tropical forest to cope with the expected impacts of climate change.

Meanwhile other research came to similar conclusions about forests outside the Amazon. A paper published in July in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences painted a grim future for Borneo’s forests. A Nature study that assessed the specific physiological effects of drought on 226 tree species at 81 sites in different biomes around the world found that forests worldwide are at ‘equally high risk’ to die-off from drought conditions, suggesting that large swathes of the world’s forests — and the services they afford — may be approaching a tipping point.

Rainforest logging debate

The debate over the sustainability of selective logging in the tropics continued in 2012. A commentary published in January in the journal Biological Conservation argued that harvest rates in tropical rainforests currently exceed the capacity of forests to regenerate timber stocks and substantially increase the risk of outright clearing for agricultural and industrial plantations. That paper was shortly followed by an article by one the co-authors in New Scientist magazine that warned of a decline in the world’s biggest trees. In the article, researcher William F. Laurance said that the loss of the oldest trees has detrimental impacts on climate, biodiversity, and forest ecology.

These arguments were partly countered by an extensive review published in the May issue of Conservation Letters, which made the case that well-managed selective logging in tropical forests should be considered a “middle way” between forest protection and outright destruction for monoculture plantations, agriculture, or livestock ranches. However a commentary published in Bioscience argued that the ecology of tropical hardwoods makes truly sustainable logging not only impractical, but unprofitable. The Bioscience said that industrial logging be excluded from subsidies under the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program.

While the academics debated, the Malaysian state of Sabah continued to move serve as a testing ground for tropical forest management. Its forests decimated by unsustainable logging from the 1970s to the mid-2000s, Sabah has been setting aside high conservation value forests — both logged and unlogged — in protected areas.

Innovation

Setting the flight path for a conservation drone. |

2012 was the year that “conservation drones” finally broke through. An effort to develop low-cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for wildlife monitoring and forest surveys made great strides this year, capped by field work in Indonesia, Nepal, Malaysia, and the Congo Basin. Google committed $5 million toward the development of remote monitoring technology for conservation.

Results from an advanced airplane-based mapping platform were published widely in 2012, including studies on forests in Madagascar, Peru, South Africa, and Colombia. The AToMS system, developed by a team at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, enables scientists to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties at a rate of 500,000 trees per minute.

In partnership with Cal State Monterey Bay and NASA Ames Research Center, Mongabay.com launched a global forest disturbance alert system (GloF-DAS)

“New” species

If prior years are any indication, 2012 will likely be a record-setter for new species discoveries. Thousands of tropical forest species were described by scientists for the first time in 2012. Among the highlights: the lesula, a monkey from DRC; an Amazonian fungus that devours plastic; three new slow loris from Borneo; dozens of new reptiles and amphibians; and several new birds.

Rainforest biodiversity

A spate of studies highlighted both how little we know about tropical rainforests and the threats to forest biodiversity.

In May a report from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) said that wildlife populations in the tropics have declined 61 percent over the past 40 years. The Living Planet Index tracks almost 10,000 populations of 2,688 vertebrate species in the tropics and temperate regions. The report was followed in July by a Nature study which found that half of assessed protected areas in the tropics suffered an “erosion of biodiversity” over the last 20-30 years.

In August, a study published in PLoS ONE documented large-scale die-off of mammal populations in long-ago isolated forest fragments in Brazil’s Mata Atlantica. Examining 18 mammal species across 196 forest fragments in the Atlantic Forest, the researchers found “unprecedented rates of local extinctions,” despite the fact that they purposefully visited the “most intact and best preserved” sites in the region. On average only about 4 target mammals were found out of 18 in each forest patch. The findings undercut assumptions made by the widely used theory of species-area relationships, which predicted that around 45-80 percent of the mammals would have remained. Worryingly even some large forest patches with intact canopies had been depleted of the target mammals.

In December, a comprehensive survey of arthropods in a rainforest in Panama found that 60-70 percent of tropical forest arthropods may be yet to be described by scientists.

Rainforest in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

REDD+

Progress on the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) mechanism stalled in 2012 as negotiations broke down, debates continued, and investment dried up due to market uncertainty. Nonetheless several projects achieved certification under the leading carbon standards, including one in Colombia and another in the DRC. Several REDD+ project developers formed Code REDD, an initiative that aims to market “high quality” REDD credits for the voluntary carbon market. Meanwhile Brazil took action against unlicensed REDD+ projects set up on indigenous territories.

Norway continued to push forth with its own climate and forests initiative. The Scandinavian country’s payments for avoiding or reducing deforestation reached $670 million in Brazil and $115 million in Guyana. Indonesia has also received more than $100 million.

The State of California launched its carbon market in November, selling $300 million worth of emissions permits to energy companies, creating the first compliance market for carbon in the United States. California’s carbon market is being carefully watched by REDD+ project developers.

Global trade and deforestation

Meanwhile, to the surprise of no one, a report from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) called out China as a major driver of illegal logging. The report alleged that China is the world’s largest importer of illegal wood products. EIA noted that unlike the U.S., the EU, and Australia, China has not enacted and enforced any laws banning imports of illegal timber. A report published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and INTERPOL estimated that illegal logging accounts for 15-30 percent of forestry in the tropics and is worth $30-100 billion worldwide.

A synthesis published in September estimated that agriculture is the direct driver of roughly 80 percent of tropical deforestation, while logging is the biggest single driver of forest degradation

Conversion of forest for an oil palm plantation in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

Deforestation-free sourcing policies

Activists and conservation groups continued their campaign to stop pulp and paper giants from clearing natural forests and peatlands on the island of Sumatra. WWF, Greenpeace, the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), Greenomics, and the Eyes on the Forest coalition all issued hard-hitting reports exposing alleged transgressions by Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL). In response, several major companies said they would implement policies to exclude paper and packaging sourced via clearing of natural forests in Indonesia. The biggest announcement came in October when Disney announced sweeping changes to its paper-sourcing policy after a protracted campaign by RAN. APP responded to the attention by announcing a “sustainability roadmap” and a partnership with The Forest Trust (TFT), which in 2011 helped salvage the reputation of the paper giant’s sister company, Golden-Agri Resources, a palm oil company. However APP’s roadmap was roundly criticized by Greenpeace and Indonesia-based Greenomics, which complained of significant loopholes. Meanwhile a coalition of environmental groups and human rights organizations urged banks not to provide finance for pulp mill expansion in Sumatra. APP subsequently hired a prominent lobbyist to help with its image in the United States.

In November Australia passed the Illegal Logging Prohibition Bill, joining the U.S. in outlawing the importation of illegal logged timber from abroad. The legislation made it a criminal offense for Australian businesses to import timber from illegal operations. Also in November, Norway’s $650 billion sovereign wealth fund said it will ask companies in which it invests to disclose their impacts on tropical forests as part of its effort to reduce deforestation. The move could usher in broader reporting on the forest footprint of operations.

Brazil

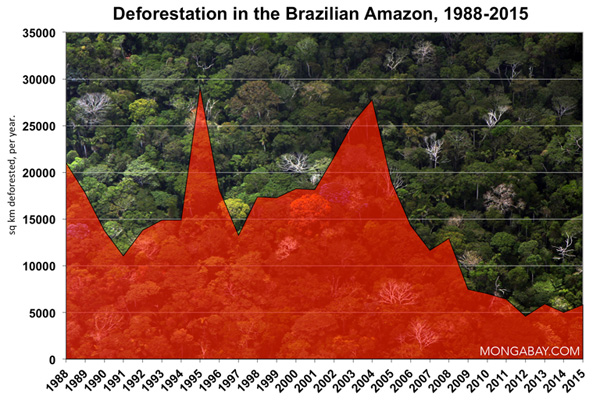

There were mixed signals for Brazil’s forests in 2012. One one hand, the Amazon deforestation fell to the lowest on record. On the other, work on the controversial Belo Monte dam moved forward, threatening one of the Amazon’s mightiest tributaries.

In the early months of 2012 it was apparent deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon continued the recent downward trend. Yet debate over legislation to reform the country’s Forest Code, which governs how much forest a private landowner is required to maintain, raised concerns among environmentalists. The new Forest Code was eventually passed in October. It maintained headline forest cover targets, but relaxed some requirements. The implications of the revision are still far from certain, but near-real time deforestation monitoring shows that forest clearing during the second half of the year is pacing well-ahead of last year’s record-low rate. It is unclear whether the increase in deforestation is associated with changes in the Forest Code or broader macroeconomic trends.

Nonetheless there were interesting political developments outside the Forest Code process. Simao Jatene — the governor of the state of Pará, which has lost more Amazon forest over the past decade-and-a-half than any other in Brazil — surprised many in the environmental movement by calling for a zero net deforestation target by 2020, arguing that Brazil doesn’t need to cut down more forest to expand agricultural production. Meanwhile the federal government in October set up a special environmental security force as part of an effort to stem the apparent rise in deforestation after July. In December, a forest quota system launched in Rio. The platform enables farmers and ranchers who have cleared forest beyond the legal minimum to come into compliance by purchasing forest ‘quotas’ from landowners who have more than the mandated level of forest cover. The emergence of the system suggests increased confidence in the ability of the Brazilian government to enforce compliance with the country’s Forest Code.

Still environmentalists weren’t entirely enthusiastic about Brazil’s direction with its forests. Damming of the Xingu River for the Belo Monte hydroelectric project got the official go-ahead despite intensive opposition from indigenous groups and environmentalists, including protests, colorful advertising campaigns, and even industrial sabotage. Brazilian companies and banks also announced plans to invest tens of billions of dollars in new infrastructure projects — including dams, mines, and roads — that some fear could worsen deforestation and adversely affect on Earth’s largest rainforests.

Finally, Brazil hosted the Rio+20 conference, which was widely viewed as a failure. Environmentalists called it a waste of time, money, and carbon.

The Amazon

Outside Brazil, there were other developments in Amazon countries. A comprehensive assessment of the region’s forest cover and drivers of deforestation was published by a coalition of 11 Latin American civil society groups and research institutions that form the Amazonian Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG). The assessment, published as a report and a series of maps, showed that forest cover across the world’s largest rainforest declined by about six percent between 2000 and 2010, while the number of oil and gas projects, dams, roads, and mining increased substantially. But RAISG also found that recognition of protected areas and native lands across the eight countries and one department that make up the Amazon is improving, with conservation and indigenous territories now covering nearly half of its land mass.

Aerial surveys of a remote area of rainforest along the Colombia-Brazil border produced the first photographic evidence of uncontacted tribes in Rio Puré National Park, an area of mostly pristine rainforest between the Caquetá and Putumayo River basins along the Brazilian border. The photos, released by the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), showed five long houses or malokas thought to belong to two indigenous groups, the Yuri or Carabayo and Passé, some of the last isolated tribes in the Colombian Amazon.

The Colombian government also announced its intention to double the size of the remote and poorly-explored Chiribiquete National Park from 1.5 to 3 million hectares. Chiribiquete will become the largest protected area in the Colombian Amazon.

Finally scientists published high-resolution carbon maps for 165,000 square kilometers (64,000 square miles) of forest across roughly 40 percent of the Colombian Amazon. The research will bolster the country’s nascent REDD+ program.

Ecuador reported some progress on its innovative yet controversial program to protect a stunningly biodiverse area of rainforest that happens to lie above 850 million barrels of oil. In November, The Guardian reported the Yasuni-ITT Initiative had raised $300 million to keep Yasuni National Park’s oil reserves in the ground. The initiative is seeking to raise $3.6 billion.

Plans for gas exploration in Manu National Park, one of the most biodiverse protected areas on Earth, spurred criticism from UNESCO and complaints from environmentalists and indigenous rights groups. Meanwhile clashes over mining and energy development continued.

In March, an extensive assessment of forests across the six-nation Congo Basin revealed that the region’s gross annual deforestation rate doubled from 0.13 percent to 0.26 percent between the 1990s and the 2000-2005 period. Gross degradation caused by logging, fire, and other impacts increased from 0.07 percent to 0.14 percent on an annual basis, according to the report, which was prepared by the the Central African Forests Commission (COMIFAC) and members of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership.

On a more hopeful front, in February the Republic of the Congo expanded its Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park by 37,295 hectares (144 square miles) to include a dense swamp forest known as the Goualougo Triangle. The area is home to large populations of chimpanzees, forest elephants, and western lowland gorillas. In July, the United Nations Education, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the Sangha Tri-National Protected Area complex (TNS) as a World Heritage Site for its density and diversity of rainforest wildlife. Formed by three contiguous national parks covering 10,000 square miles (25,000 sq km) in Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), Cameroon, and the Central African Republic, TNS is the first World Heritage Site to span three countries.

Shortly after the UNESCO declaration, tragedy struck in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) when a militia linked to poaching and illegal mining slaughtered conservation workers and okapi at the headquarters of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. Seven people and 14 okapi were killed. The massacre was only many of many acts of violence against rangers and conservation workers in DRC during 2012.

In Cameroon, work on a controversial oil palm plantation moved forward despite a stepped-up campaign by activists. In March, eleven prominent scientists criticized the plan by Herakles Farms to convert 70,000 hectares of land for palm oil production. The scientists expressed concern about the impacts of the plantation on biodiversity as well as alleged opposition from some locals. They noted that Herakles had apparently broken rules set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a certification initiative that sets basic social and environmental standards for palm oil production. In September, Herakles announced it wouldn’t seek RSPO-certification for the plantation. In November, Greenpeace released aerial photographs showing conversion of rainforests for oil palm within Herkakles’ concession area.

Malaysia

Campaigners turned up the heat on Sarawak Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud. An investigation by the Bruno Manser Fund uncovered large financial holdings allegedly linked to the long-ruling leader. The group estimated Taib’s personal wealth at $15 billion despite more than 30 years of earning a civil-servant’s salary, which it said is evidence of large-scale corruption. Taib was also hit by protests against planned dams and the cancellation of a $2 billion aluminum smelter that was being used to justify the state’s dam-building ambitions. Banking giant HSBC got caught up in the controversy when Global Witness accused it of providing finance to companies linked to rainforest destruction and invasion of indigenous land in Sarawak.

Rainforest in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

India

India continued to receive mixed reviews for its environmental record. In February, the Prime Minister’s Office opened up 25 percent of the country’s protected forests for coal mining, roads, and industrial development. In the months that followed, Coal India Ltd., the world’s largest coal producer, announced it plans to massively expand mining in forest areas to help meeting surging demand for electricity. A Greenpeace report warned that India’s coal expansion would directly threaten the country’s most famous animal — the tiger.

Tigers in India aren’t only threatened by coal. In June, authorities announced that nearly 50 tigers had been found dead across India. The situation was so bad in the state of Maharashtra that authorities granted legal immunity to any forest ranger who shoots a poacher.

However not all the news was bad for wildlife in India in 2012. WCS reported a recovery of tigers in the Western Ghats region, which in July was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO for its high levels of biodiversity. Meanwhile a report by an expert panel recommended a phase-out of mining projects, damaging hydroelectric projects, and industrial agricultural in ecologically-sensitive sections of the Ghats.

Cambodia

With one of the world’s highest rates of primary forest loss and a series of controversial concessions granted to foreign companies in key forest areas, Cambodia is widely viewed as an environmental pariah. But things took a turn for the worse with several high profile murders of environmentalists in 2012. In April forest activist Chut Wutty was shot dead at an illegal logging site by military police. His killing — which journalists say was not properly investigated — was followed in September by the brutal slaying of Hang Serei Oudom, a journalist who often reported on illegal logging, and a subsequent attack on environmental journalist Ek Sokunthy

In March, the Cambodian government sold nearly 20 percent of Botum Sakor National Park to a Chinese real-estate firm building a massive casino and resort complex. However in August, following large-scale community protests, the government canceled four concessions covering 40,000 hectares of Prey Lang forest.

Papua New Guinea

The controversy over special agricultural and business leases (SABLs) granted to foreign corporations operating in Papua New Guinea (PNG) continued in 2012. In July, Greenpeace published a report detailing cases where community land had been granted to logging companies. Meanwhile conflict between loggers and communities continued, including an incident where a group of local landowners in East New Britain were alleged imprisoned in shipping containers.

Philippines

Rampant illegal logging and mining was blamed for worsening the devastating Typhoon Bopha that killed hundreds on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

Indonesia

In 2012 Indonesia entered its second year of its moratorium on new concessions in 14.5 million hectares of previously unprotected peatlands and rainforests. The moratorium —which continued to be criticized by environmentalists and even its chief backer, Norway — was put to a test with a case involving an oil palm plantation in the Tripa peat swamp in Aceh, Sumatra. After a long-standing campaign by environmentalists and local communities, the Indonesian government formally investigated the concession and found “irregularities” in the company’s permit, leading it to revoke the plantation’s operating permit. PT Kallista Alam, the company that operated the concession, subsequently sued the government for revoking the permit.

Activist campaigns against conversion of forests and peatlands for oil palm plantations and pulp and paper production continued, with several notable companies dropping suppliers linked to deforestation. Pulp & Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) were particular targets. But the palm oil and pulp industries fought back, launching campaigns of their own against environmental groups within Indonesia and abroad. After Disney announced a new sourcing policy that would exclude fiber sourced from clearing of rainforests, a paid mob demonstrated in front of the U.S. embassy in Jakarta and Greenpeace’s office.

A study published in Nature Climate Change revealed the impact of oil palm expansion in Borneo: 90 percent of oil palm plantations in the study area in West Kalimantan occurred at the expense of forests. Another study, published in Environmental Research Letters, documented a 40 percent decline in Sumatra’s old-growth forest cover since 1990. But the research also showing that the rate of deforestation on the island has slowed in recent years.

Indonesia’s House of Representatives moved to establish ‘North Kalimantan’, a new province in Indonesian Borneo, and voted for four new districts: Pangandaran in West Java, South Coast in Lampung, and South Manokwari and Arfak Mountains in West Papua. While the moves aim to improve governance by boosting local autonomy, they raised fears of increased deforestation.

During climate talks in Doha, The Indonesian government announced the approval of the Rimba Raya, the country’s first Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) project. Rimba Raya aims to protect and restore nearly 80,000 hectares of forest in Central Kalimantan. The project’s backers include Russian energy giant Gazprom and the insurance firm Allianz.