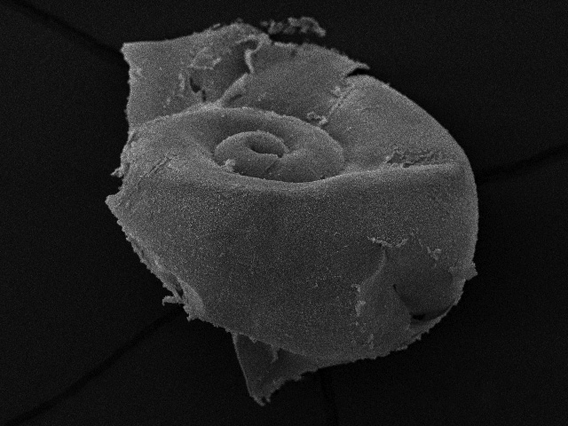

Marine snails, known as Limacina helicina antarctica, are seeing their shells dissolve due to carbon emissions. Photo by: Nina Bednarsek.

Marine snails, also known as sea butterflies, are dissolving in the Southern Seas due to anthropogenic carbon emissions, according to a new study in Nature GeoScience. Scientists have discovered that the snail’s shells are being corroded away as pH levels in the ocean drop due to carbon emissions, a phenomenon known as ocean acidification. The snails in question, Limacina helicina antarctica, play a vital role in the food chain, as prey for plankton, fish, birds, and even whales.

“This is actually happening now,” lead author, Geraint Tarling of the British Antarctic Survey, told the New Scientist.

Carbon emitted into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, cutting forests, or industrial agriculture doesn’t always stay there, a significant amount of the carbon is sequestered by the ocean—otherwise the world would be heating up far faster than it is. However, this extra carbon in the ocean comes with a price: ocean acidification, which U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Jane Lubchenco, recently dubbed “climate change’s equally evil twin.” .

As it changes the chemical-makeup of the seas, ocean acidification could have massive impacts on the health and survival of corals, crustaceans, molluscs, and even some plankton by dissolving shells and plates made from calcium carbonate. For its part, Limacina helicina antarctica depends on aragonite, a type of calcium carbonate, which is the extremely vulnerable to dropping pH levels.

Researchers used electron microscopes to study Limacina helicina antarctica caught at the surface of the Southern Ocean and found “severe levels of shell dissolution,” according to the paper. The snails were caught in an upwelling—an area where deep, cold water is pushed to the surface—which naturally depletes the availability of aragonite. When combined with ocean acidification, the natural upwelling had taken a large toll on the sea butterflies’ shells. To date, this is one of the first time such impacts have been discovered in the wild, and not just the laboratory.

“The snails do not necessarily die as a result of their shells dissolving, however it may increase their vulnerability to predation and infection, consequently having an impact to other parts of the food web,” Tarling said in a press release.

The cold water of the Southern Ocean means that wildlife here is the first to be impacted by ocean acidification. However, as the oceans sequester more carbon, impacts are expected to expand beyond the poles.

Scientists have long warned that the simplest way to combat ocean acidification is to cut carbon emissions into the atmosphere. However, global carbon emissions continue to rise with a new analysis in Nature Climate Change predicting that industrial emissions will jump another 2.6 percent in 2012, hitting a new record.

Limacina helicina antarctica are around a centimeter in size and are an abundant species in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica.

A scanning electron microscope of a sea butterfly with acute levels of shell dissolution. Photo by: Nina Bednarsek.

CITATION: N. Bednaršek, G. A. Tarling, D. C. E. Bakker, S. Fielding, E. M. Jones, H. J. Venables, P. Ward, A. Kuzirian, B. Lézé, R. A. Feely & E. J. Murphy. Extensive dissolution of live pteropods in the Southern Ocean. Nature Geoscience 5, 881–885. 2012. doi:10.1038/ngeo1635.

Related articles

Threatened Galapagos coral may predict the future of reefs worldwide

(11/07/2012) The Galapagos Islands have been famous for a century and a half, but

even Charles Darwin thought the archipelago’s list of living wonders

didn’t include coral reefs. It took until the 1970s before scientists

realized the islands did in fact have coral, but in 1983, the year the

first major report on Galapagos reef formation was published, they

were almost obliterated by El Niño. This summer, a major coral survey

found that some of the islands’ coral communities are showing

promising signs of recovery. Their struggle to survive may tell us

what is in store for the rest of the world, where almost

three-quarters of corals are predicted to suffer long-term damage by

2030.

Coral calcification rates fall 44% on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

(09/04/2012) Calcification rates by reef-building coral communities on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef have slowed by nearly half over the past 40 years, a sign that the world’s coral reefs are facing a grave range of threats, reports a new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research – Biogeosciences.

Earth’s ecosystems still soaking up half of human carbon emissions

(08/06/2012) Even as humans emit ever more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, Earth’s ecosystems are still sequestering about half, according to new research in Nature. The study finds that the planet’s oceans, forests, and other vegetation have stepped into overdrive to deal with the influx of carbon emitted from burning fossil fuels, but notes that this doesn’t come without a price, including the acidification of the oceans.

2,600 scientists: climate change killing the world’s coral reefs

(07/10/2012) In an unprecedented show of concern, 2,600 (and rising) of the world’s top marine scientists have released a Consensus Statement on Climate Change and Coral Reefs that raises alarm bells about the state of the world’s reefs as they are pummeled by rising temperatures and ocean acidification, both caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The statement was released at the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium.

World failing to meet promises on the oceans

(06/14/2012) Despite a slew of past pledges and agreements, the world’s governments have made little to no progress on improving management and conservation in the oceans, according to a new paper in Science. The paper is released just as the world leaders are descending on Rio de Janeiro for Rio+20, or the UN Summit on Sustainable Development, where one of the most watched issues is expected to be ocean policy, in part because the summit is expected to make little headway on other global environmental issues such as climate change and deforestation. But the new Science paper warns that past pledges on marine conservation have moved too slowly or stagnated entirely.