27% less forest chopped down in the Brazilian Amazon

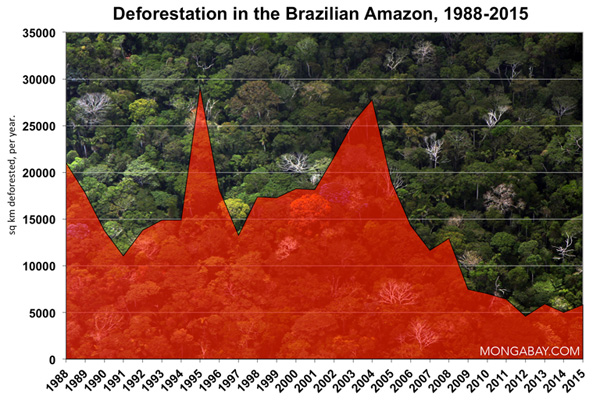

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell to the lowest rate since annual record-keeping began in 1988 according to provisional data released Tuesday by Brazil’s National Space Research Agency (INPE).

1,798 square miles (4,656 square kilometers) of Amazon forest was chopped down during the 12 months ending July 31, 2012, 27 percent less than the year earlier period. According to INPE, Brazil’s rate has dropped 76 percent relative to the baseline established for its 80 percent reduction target for 2020.

The government attributes the drop in deforestation to improved law enforcement and better satellite monitoring in the region. Brazil has also set aside vast areas of rainforest in protected areas and indigenous reserves over the past decade. However independent analysts suggest the gains have been underpinned by macroeconomic trends — including a strong real (Brazil’s currency) — that have made it less profitable for Brazilian farmers and ranchers to expand production into forest areas. Commodity buyers in overseas markets also seem less willing to have their products associated with deforestation, contributing to a shift in practices.

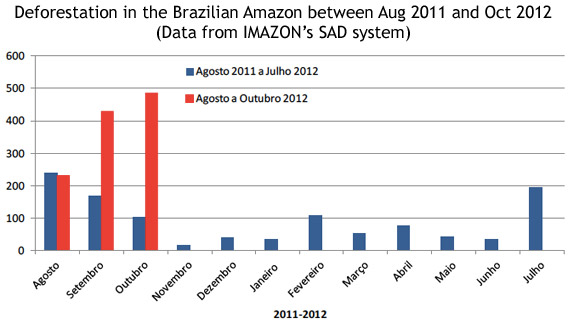

However there are worrying signs that the downward trend may be at risk of reversal. Data released by Imazon, a Brazilian NGO, shows that deforestation since August 1, 2012 is tracking well ahead of last year’s pace (INPE has not provided a public update on its near-real time deforestation tracking system since September). Meanwhile the country just passed a revised version of its Forest Code, which governs how much forest landowners are permitted to clear in the Amazon and other regions. Environmental groups say the changes effectively loosen the rules for ranchers and farmers, potentially spurring more deforestation. At the same time, BNDES, Brazil’s national development bank, is allocating tens of billions of dollars a year to new Amazon infrastructure projects—including dams and roads—which could increase pressure on forests, both inside and outside Brazil. Finally, the weakening real could improve the profitability of Brazilian agriculture, driving expansion.

Scientists are also concerned about ecological trends in the Amazon. Specifically, in 2005 and 2010 the region suffered the two worst droughts ever recorded. The droughts — which have now been tied to warmer temperatures in the tropical Atlantic — sparked widespread fires, shrank rivers, and led to forest die-off across large swathes of the Amazon. Researchers fear that the intensity and frequency of such incidents could increase with rising global temperatures.

The fate of the Amazon has important implications for humanity. Forests in the region store more than 80 billion tons of carbon, serve as a refuge for hundreds of thousands of plant and animal species, and influence global weather patterns, including supplying water to areas that produce 70 percent of South America’s GDP.

Related articles