A captive Kihansi spray toad at the WCS Bronx Zoo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

In 1996 scientists discovered a new species of dwarf toad: the Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis). Although surviving on only two hectares near the Kihansi Gorge in Tanzania, the toads proved populous: around 17,000 individuals crowded the smallest known habitat of any vertebrate, living happily off the moist micro-habitat created by spray from adjacent waterfalls. Eight years later and the Kihansi spray toad was gone. Disease combined with the construction of a hydroelectric dam ended the toads’ limited, but fecund, reign. However, before the toad population collapsed completely conservationists with the Wildlife Conservation Society’s (WCS) Bronx Zoo were able to establish a captive population of 499 frogs. Now, researchers are releasing a seed population of Kihansi spray toads back into their native habitat, but with one caveat: an artificial “misting system” is the only thing standing between the tiny amphibians and a second extinction.

“As long as the hydroelectric dam persists, the misting system will be needed in order to provide sufficient ‘spray meadow’ habitat at the base of Kihansi Falls for the single Kihansi Spray Toad population to persist,” Don Church the President and Director of Wildlands Conservation with Global Wildlife Conservation told mongabay.com. “The energy company [running the dam], TANESCO, is mandated to allow some water over the dam so that the river and Kihansi Falls do not dry up. However, the spray zone generated by Kihansi Falls is vastly reduced compared to what it was before the dam was constructed.”

In what may be the first time conservationists have ever re-established an “extinct” species in a human-engineered ecosystem, conservationists released around 2,500 amphibians this week. The effort is a culmination of years of a work by multiple groups—the Tanzania’s National Environmental Management Council (NEMC), the University of Dar Salaam, the Toledo Zoo, WCS, the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group, the IUCN SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, and Global Wildlife Conservation—to save the toads from extinction and bring them back to their spray meadows.

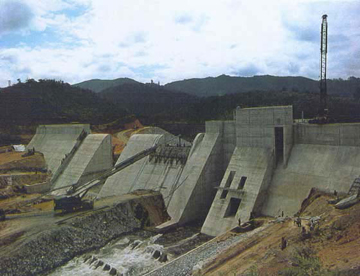

Kihansi River dam. Photo by: UNESCO. |

The conservation work has moved remarkably fast. Today’s captive population has grown 12-fold from its beginning in 2004, while frogs are being released only three years after the IUCN announced they were extinct in the wild.

“Most reintroductions for amphibians and reptiles have been designed to establish or augment a population of a rare species, but it is extremely exciting to be involved in actually returning a species that was extinct in the wild back to its native habitat.” said Kurt Buhlmann and Tracey Tuberville, research scientists with the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory.

The misting system, engineered especially for this issue, was developed as recompense for the environmental damage caused by the dam, which was funded by the World Bank and the government of Noway.

“[It] diverts water from above the fall through a network of pipes with misting heads at regular intervals and effectively creates a spray zone over a broader area than the Kihansi Falls, in its current state, can generate,” Church explains. “The system is maintained to deliver 70 mm of ‘precipitation’ per day which was the average amount recorded in the “spray meadow” prior to the dam’s construction.”

The manmade structure also includes bridges around the gorge where scientists can monitor the progress of the tiny frogs.

A brilliant yellow, the Kihansi spray toad is a small enough to fit on a human thumbnail, and unlike most amphibians actually bears live young. While the dam desiccated its habitat, the toad population also suffered from the killer chytridiomycosis fungus near the end. This amphibian disease, which has spread quickly worldwide, has already pushed a number of once abundant species to the brink and is one reason why amphibians are among the most endangered of the world’s animal groups. Currently, the IUCN Red List estimates that over 40 percent of amphibians are under threat, while more than 150 species are believed to have gone extinct since the early 1980s.

“The success story of the small Kihansi Spray Toad can teach us big lessons for the future of biodiversity conservation,” Claude Gascon, the co-chair of the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group, Claude Gascon, said. “While amphibians and other species are incurring severe threats to their survival, it is never too late to use the best science and conservation action to save a species and its habitat.”

While the story of the Kihansi spray toad remains one of the happier ones for frogs lately, only time will tell if the toads will thrive in their engineered habitat—and, perhaps, only philosophers can tell us if a wild animal is still wild if it depends on a human-constructed ecosystem for survival.

Misting system provides constant moisture for the frog’s habitat. Photo courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

Kihansi Falls. Photo courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

-1.568.jpg)

Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis). Photo courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

Kihansi upper spray wetland sign. Photo courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

Related articles

Climate change may be worsening impacts of killer frog disease

(08/13/2012) Climate change, which is spawning more extreme temperatures variations worldwide, may be worsening the effects of a devastating fungal disease on the world’s amphibians, according to new research published in Nature Climate Change. Researchers found that frogs infected with the disease, known as chytridiomycosis, perished more rapidly when temperatures swung wildly. However scientists told the BBC that more research is needed before any definitive link between climate change and chytridiomycosis mortalities could be made.

3000 new species of amphibians discovered in 25 years

(07/31/2012) The number of amphibians described by scientists now exceeds 7,000, or roughly 3,000 more than were known just 25 years ago, report researchers in Berkeley.

Vampire and bird frogs: discovering new amphibians in Southeast Asia’s threatened forests

(02/06/2012) In 2009 researchers discovered 19,232 species new to science, most of these were plants and insects, but 148 were amphibians. Even as amphibians face unprecedented challenges—habitat loss, pollution, overharvesting, climate change, and a lethal disease called chytridiomycosis that has pushed a number of species to extinction—new amphibians are still being uncovered at surprising rates. One of the major hotspots for finding new amphibians is the dwindling tropical forests of Southeast Asia.

(01/03/2012) The chytrid fungus, which is responsible for the collapse of numerous amphibian populations as well as the extinction of entire species, has been located for the first time in India, according to a paper in Herpetological Review. Researchers took swabs of frog in the genus Indirana in the Western Ghats and found the killer fungus known as chytridiomycosis.

Photos: two new paper clip-sized frogs discovered in Vietnamese mountains

(12/07/2011) Researchers have discovered two new frog species living in the montane tropical forests of Vietnam. Known as moss frogs, these small amphibians employ camouflage as one way to keep predators at bay, in some cases resembling the moss that gives them their name.

Effort to save world’s rarest frogs recognized with conservation award

(12/05/2011) An effort to save the world’s most endangered amphibians has won mongabay.com’s 2011 conservation award. Amphibian Ark — a joint effort of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the IUCN/SSC Amphibian Specialist Group — is working to evaluate the status of threatened amphibians, raise awareness about the global amphibian extinction crisis, and set up captive breeding programs. The initiative is targeting 500 species that will not survive without captive breeding efforts.