Climate threat to lemurs

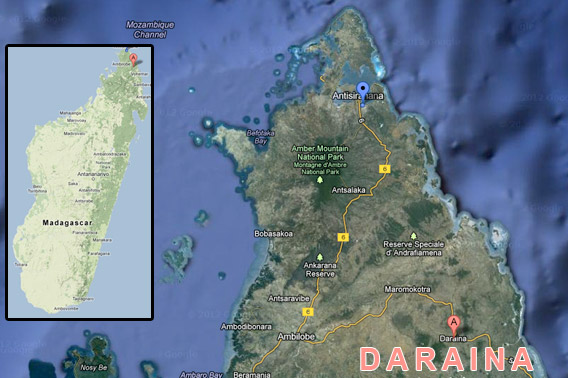

Daraina region in Madagascar. Background image from Google Earth.

Climate change that took place 4,000-10,000 years ago may have contributed to the endangered status of one of Madagascar’s rarest lemurs by reducing the extent of its habitat, argues a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences.

The research, conducted by a team of French scientists, used remote-sensing analyses and population genetics modeling to reconstruct the historical distribution of golden-crowned sifaka (Propithecus tattersalli), a forest-dwelling lemur, in the Daraina region in northern Madagascar. They found the lemur’s habitat underwent a sharp contraction during dry periods caused by climate change.

The findings are significant because they indicate the species suffered a population drop prior to the arrival of humans some 1500-2000 years ago. Humans, through their use of fire, are usually seen as responsible for large-scale vegetation change across the island nation, but the study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that Madagascar may not have been as forested as conventionally believed at the time of human colonization.

Golden-crowned Sifaka (Propithecus tattersalli). Photo by Jeff Gibbs. |

“Prehuman Holocene droughts may have led to a significant increase of grasslands and a reduction in the species’ habitat,” write the authors. “This contradicts the prevailing narrative that land cover changes are necessarily anthropogenic in Madagascar but does not preclude the later role played by humans in other regions in which recent lemur bottlenecks have been observed.”

In other words, while climate change may have triggered the observed decline in the golden-crowned sifaka’s forest habitat, the authors say that humans could have been responsible for forest loss on other parts of the island. For example, satellite data and aerial photography show that forest cover has indeed declined significantly in the past 50 years across large areas of the island due to agricultural conversion and land-clearing to establish cattle grazing areas.

Nevertheless, the authors note that in their particular study area, forest cover has remained stable for 60 years, indicating that the local population is not necessarily responsible for the golden-crowned sifaka’s endangered status.

“There is no doubt that humans have played a major role in driving several Malagasy species to extinction, since their arrival on the island,” co-author Lounès Chikhi of the Université Paul Sabatier said in a statement. “Although our findings relate to a specific region in Madagascar, they shine the spotlight on how important it is that conservation projects account for regional differences. The presence of humans, we have demonstrated, may not be the only cause for loss of biodiversity. It is risky to alienate local communities by excluding them from their territories, rather that bringing them on as precious allies to help conservationists find local answers for sustainable resource management.”

CITATION: Erwan Quéméré, Xavier Amelot, Julie Pierson, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, and Lounès Chikhi (2012). Genetic data suggest a natural prehuman origin of open habitats in northern Madagascar and question the deforestation narrative in this region. PNAS 2012: 1200153109v1-201200153.

Related articles

91% of Madagascar’s lemurs threatened with extinction

(07/13/2012) 94 of the world’s 103 lemur species are at risk of extinction according to a new assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) released by the group’s Species Survival Commission during a workshop this week. Lemurs, a group of primates that is endemic to the island of Madagascar, are threatened by habitat destruction and poaching for the bushmeat trade.

How lemurs fight climate change

(01/09/2012) Kara Moses may have never become a biologist if not for a coin toss. The coin, which came up heads and decided Moses’ direction in college, has led her on a sinuous path from studying lemurs in captivity to environmental writing, and back to lemurs, only this time tracking them in their natural habitat. Her recent research on ruffed lemurs is attracting attention for documenting the seed dispersal capabilities of Critically Endangered ruffed lemurs as well as theorizing connections between Madagascar’s lemurs and the carbon storage capacity of its forests. Focusing on the black-and-white ruffed lemur’s (Varecia variegata) ecological role as a seed disperser—animals that play a major role in spreading a plant’s seeds far-and-wide—Moses suggests that not only do the lemurs disperse key tree species, but they could be instrumental in dispersing big species that store large amounts of carbon.

Critically Endangered lemurs disperse seeds, store carbon

(11/13/2011) Many tropical plants depend on other species to carry their progeny far-and-wide. Scientists are just beginning to unravel this phenomenon, known as seed dispersal, which is instrumental in supporting the diversity and richness of tropical forests. Researchers have identified a number of animal seed dispersers including birds, rodents, monkeys, elephants, and even fish. Now a new study in the Journal of Tropical Ecology adds another seed disperser to that list: the Critically Endangered black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata). Capable of dispersing big tree species, the black-and-white ruffed lemur may even play a big role in carbon sequestration.

Already on the edge, lemurs could become victims of climate change

(06/08/2010) Expanding beyond well-known victims such as polar bears and coral reefs, the list is growing of species likely to be hard hit by climate change: from lizards to birds to amphibians. Now a new study has uncovered another group of species vulnerable to a warmer world: lemurs.

Natural rafts carried Madagascar’s unique wildlife to its shores

(01/20/2010) Imagine, forty million years ago a great tropical storm rises up on the eastern coast of Africa. Hundreds of trees are blown over and swept out to sea, but one harbors something special: inside a dry hollow rests a small lemur-like primate. Currents carry this tree and its passenger hundreds of miles until one gray morning it slides onto a faraway, unknown beach. The small mammal crawls out of its hollow and waddles, hungry and thirsty, onto the beach. Within hours, amid nearby tropical forests, it has found the sustenance it needs to survive: in a place that would one day be named Madagascar.

Climate Change Threatens Lemurs

(09/18/2006) Tropical rainforests are among the most stable environments on Earth, but they are still no match for global climate change. Dr. Patricia Wright, the widely admired primatologist and Professor of Anthropology at Stony Brook University, finds that climate change could mean the difference between survival and extinction for endangered lemurs.