This is an expanded version of an article, titled A Desperate Effort to Save the Rainforest of Borneo, that appeared last month on Yale e360.

Rainforest in Sabah. All photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

For most people “Borneo” conjures up an image of a wild and distant land of rainforests, exotic beasts, and nomadic tribes. But that place increasingly exists only in one’s imagination, for the forests of world’s third largest island have been rapidly and relentlessly logged, burned, and bulldozed in recent decades, leaving only a sliver of its once magnificent forests intact.

Flying over Sabah, a Malaysian state that covers about 10 percent of Borneo, the damage is clear. Oil palm plantations have metastasized across the landscape. Where forest remains, it is usually degraded. Rivers flow brown with mud.

But if you travel far enough in Sabah, some of Borneo’s most treasured forest does still exist. Beyond the oil plantations and logged-over zones there remain patches of stunning lowland and montane forest. Colorful hornbills soar over the broccoli-like canopy, orangutan nests sit high in the treetops, and clear streams cascade over waterfalls. The fact these areas remain seems almost miraculous given the state of the surrounding countryside and the vast amounts of money that have been made from the plunder.

Borneo’s forests, like those in the Philippines, Sumatra, and other parts of Asia, are largely the victim of a cycle that begins with selective logging and ends with conversion to industrial plantations, agriculture, or scrubland. The cycle is closely tied to the political economy of the region—politicians have historically relied on forestry to finance their campaigns and serve as their honeypot to reward their patrons. The cycle continues today. In April, documents allegedly leaked by Malaysia’s Anti-Corruption Commission revealed the transfer of millions of dollars to bank accounts linked to Sabah’s chief minister Musa Aman. Meanwhile Sarawak’s chief minister and his close family are under investigation for acquiring billions of dollars’ worth of overseas assets from their timber dealings.

Heavily logged forest in Sabah.  Heavily logged forest in Sabah. All photos by Rhett A. Butler. |

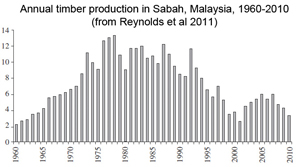

In Borneo, intensive logging began after the end of the Second World War. Sabah and Sarawak, where tall and straight rainforest trees produced some of the world’s most valuable hardwood timber stocks, were the first to be targeted. In the early days, only the most valuable and easily accessible trees were cut. But pressure to generate cash would eventually change that approach.

Sabah’s forest management was borne of good intentions. In 1966, the government set aside a vast tract of remote rainforest to be managed by Yayasan Sabah, a state-directed foundation, into perpetuity for the benefit of the people of Sabah. The forest was to be logged on an 80-year cycle to ensure financial—if not ecological—sustainability. The concession would eventually cover some one million hectares of forest.

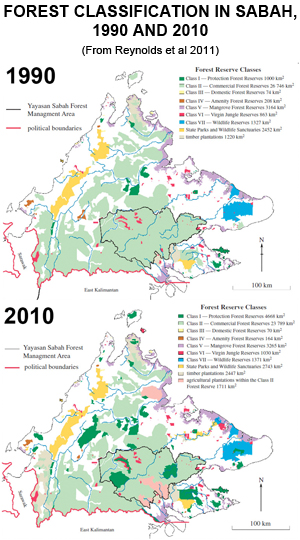

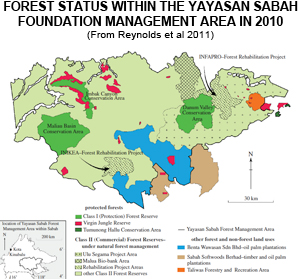

Map showing Yayasan Sabah Foundation Management Area in 2010. From a paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by Reynolds el al (2011). |

The first years of the scheme went well. Forest regulations were generally respected and a generation of Sabahans benefitted from millions of dollars in scholarships and poverty alleviation programs. Businesses did well too: the coastal city of Sandakan—Sabah’s wood processing and trading hub—in the early 1980s boasted of having the highest concentration of millionaires on the planet, mostly from the state’s timber industry.

But the political economy would interfere. In Malaysia, taxes generated from forestry accrue to the state, rather than the federal government. When times are lean, such as when the state government is controlled by a party in opposition to the federal government’s ruling party, forestry becomes a key source of revenue. Forests not only became the state’s principal rainy day fund, but came to be seen as a money pot for politicians. The biggest potential beneficiary was the chief minister, who controls both Yayasan Sabah and appoints the director of the forestry department, obliging the most senior forest official to abide by his orders, regardless of the motivations behind them. The situation is similar in Indonesia. A study published last year by researchers at the London School of Economics, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and South Dakota State University concluded that politicians in forest-rich districts repay their election debts by granting forest concessions.

“Yayasan Sabah has been a cash register for politicians,” said one senior forestry official. “Yayasan Sabah has huge area but is nearly insolvent because all the timber money has been taken out by politicians.”

A push to generate more cash began to take a toll. In the 1970s, logging accelerated in forests across Borneo, including Sabah, due to rising global consumption for timber products. Little of the logging in Sabah was illegal, but the rules were less tightly enforced and concessions more purposefully granted. By 1990 most of the Yayasan Sabah area had been selectively logged. Roughly 15 percent of the concession was still primary forest.

|

The situation for forests outside the area designated as permanent forest estate by the government was worse due to the emergence of a new and highly profitable crop: oil palm. Forest conversion for oil palm was rapid—oil palm plantations in Sabah grew from a negligible number in the mid-1980s to more than 1.4 million hectares—nearly a fifth of Sabah’s land mass—by 2010. The vast majority of forest conversion for oil palm occurred in areas legally zoned for agricultural conversion. These were generally lowland areas suitable for industrial agriculture. Concessions are were granted to palm oil developers as 99-year leases.

Inside the Yayasan Sabah concession, which by 1990 represented about one-third of Sabah’s commercial forest estate, timber volume began to fall in the 1990s after the re-logging of areas on rotations far shorter than the 60-year cycle originally prescribed. As production waned, loggers adopted more desperate measures, using helicopters to harvest steep slopes, cutting ever-smaller trees, and targeting species beyond the valuable Dipterocarps. A series of chief ministers, who rotated every two years from 1994-2003, exacerbated the demand for short-term campaign finance.

Yayasan Sabah’s revenue plunged with timber yields. The situation reached a crescendo in 1998 when the-then chief minister signed off on a white elephant project—a massive pulp mill—to be run as a Malaysian-Chinese joint venture. The mill would require 300,000 ha of Yayasan Sabah’s concession to be cleared and planted with fast-growing acacia. The project had no management plan, other than to jettison any semblance of sustainable forest management and scale up annual harvesting fourfold. When Sam Mannan, then director of forestry, objected to the project, he was relieved of his post by Sabah’s chief minister.

Timber plantation in Sabah. |

Parts of the project area were laid to waste. But it was all for naught—the pulp project never materialized. However even with the official abandonment of the mill in 2001, logging continued, eventually serving as a catalyst for early re-logging of nearly 750,000 hectares of Yayasan Sabah. Logging generated a short upswing in revenue for Yayasan Sabah, but it wasn’t sustainable. The long-term economic outlook for Yayasan Sabah was bleak.

Eventually restored to his post as director of forestry, Sam Mannan moved forward with a radical plan for addressing Yayasan Sabah’s budget shortfall: establish oil palm plantations on 100,000 hectares of land cleared for the non-existent pulp plantations.

“Yayasan Sabah is a major source of revenue for socio-economic development,” said Mannan. “I’m not going to punish them for past transgressions, including some that may have been our fault for not being assertive enough in the past.”

“If Yayasan Sabah fails, we’ll all eat grass. It won’t be able to meet its economic obligation.”

The plan, while controversial, won a special exemption. Mannan expects it to generate more revenue for Yayasan Sabah than logging ever did.

But while the forestry department said oil palm will only last for one rotation—20 to 25 years—some fear that it could become a trend, with oil palm plantations nibbling away at Sabah’s forest estate.

“The problem is whenever there are calls for money, further areas could be pared away,” said Glen Reynolds, an ecologist who last year published a seminal paper on the condition of Sabah’s forests. “The big risk in Yayasan Sabah is conversion of what’s left of Sabah’s lowland forest. For many taxa in Sabah it’s hard to see a difference between logged forests and primary forests. Catastrophic losses occur when there is conversion to plantations.”

But Mannan says doing nothing is a bigger threat. If Yayasan Sabah’s concession doesn’t meet its economic obligations, he fears that poor returns could take it out of the department of forestry’s control, turning it over to oil palm developers for good.

“Forestry is no longer the reliable source of revenue to keep the government going,” he said. “It is oil palm that is saving us and the forests.”

“I gave out 100,000 ha of heavily degraded land [for oil palm] to save 900,000 ha of forest. The one billion ringgit we expect in oil palm revenue means avoiding logging a 200,000 ha of forests a year.”

Clearing for oil palm in Sabah. |

Mannan believes oil palm can offer a bridge for the 20-year drought in revenue he foresees for Sabah’s forestry industry.

“Whatever we do today, we still face a 20-year famine. We must plan for that gap. The forests of Sabah have given so much to so many people. Now it’s payback time for all the damage that has been done. We need to invest in and restore Sabah’s forests.”

Sam Mannan |

Some of Sabah’s forests are so wrecked, they might not recover to their original structure, with a closed canopy of tall hardwoods. So the department of forestry is pushing active management of forest areas, cutting choking vines and doing “enrichment planting” with native trees. The long-term plan is to restore the forests to a state of health where they can be logged again, albeit under more stringent guidelines set forth under the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), an eco-certification body. The Sabah Forestry Department is targeting 2014 for full certification of Sabah’s forest concessions. At the same time there is experimentation occurring in parts of the Yayasan Sabah concession, including the world’s first Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) project—established in 1992—and the Malua Biobank, which generates biodiversity credits as wildlife and forest function return to a heavily logged tract of forest.

“One of the strategies within the forestry department is linking with the FSC because it binds loggers to compliance,” said the forestry official. “So if a chief minister or a politician wants to log, it becomes controversial because we’ve got areas that are FSC-certified. It becomes more difficult for politicians to use for personal ATM.”

Logging road in Sabah.  Clearing of hillsides for oil palm in Sabah. |

And critically, due also to efforts by Yayasan Sabah itself, the last remaining lowland primary forests—like Imbak Canyon, Danum Valley, and Maliau Basin—are already set aside as Class I forest reserves for strict conservation with Sabah’s Forestry Department recently taking additional steps to ensure their protection. In April, the agency re-designated roughly 155,000 ha of Class II commercial logging area—150,000 ha within the Yayasan Sabah concession—as Class I reserves, including new buffer zones around primary forests in Danum Valley and Maliau Basin.

“Sabah is still way ahead of Sarawak and Kalimantan: surviving primary forests areas are being conserved, reforestation and forest restoration is happening, and encroachers have moved out of forest reserves,” said John Payne, a conservation scientist with the Borneo Rhino Alliance. “The fear is the next government or director of forestry will convert forest concessions to oil palm. So Sam Mannan seems to be doing everything he can to publicize and put money into those reserves. His biggest achievement is securing the lowland forest reserves.”

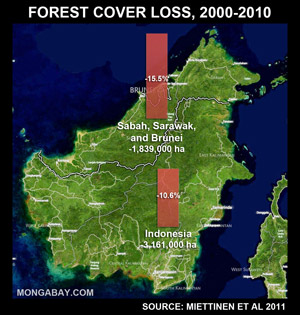

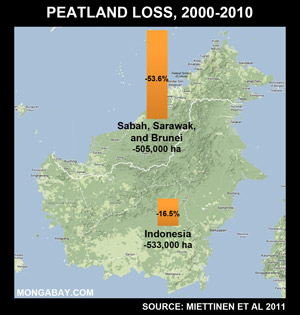

Forest and peatlands loss in Borneo, 2000-2010. Background image in top chart is courtesy of Google Earth; lower courtesy of Microsoft Bing Maps and NASA. Click images to enlarge. |

Sabah’s lowland forests have been nearly wiped out, but overall forest cover fell by a more modest 15 percent between 1990 and 2010. Compared with its Bornean contemporaries of Sarawak and Indonesia’s Kalimantan (excluding the tiny oil-rich sultanate of Brunei), Sabah’s situation doesn’t look quite as bad.

Sarawak’s forests have seen an environmental Armageddon over the past 30 years. Its forests have gone through multiple cycles of intensive logging and now are being rapidly converted for plantations. Conflict between developers and indigenous populations over native customary lands plagues the state, which is now embarking on a series of dam projects that promise to inflame tensions further. Meanwhile the four provinces that make up Kalimantan continue to suffer high rates of deforestation—3.1 million hectares between 2000 and 2010, according to a study by researchers at the National University of Singapore. Unregulated logging is rampant in Kalimantan—56 percent of protected lowland forest was lost between 1985 and 2001. In Central Kalimantan alone, anti-corruption authorities estimate that illegal mining and plantation operations cost the province 158.5 trillion rupiah ($17.6 billion).

Sabah’s transition to a different type of forest management is by no means assured. The lure of oil palm remains strong and politicians still have the same needs and temptations. But resource depletion has become a factor unto itself, according to a senior Sabah official: “If it’s getting better it’s because there’s less forest. The pot of gold is smaller.”

What happens in Sabah could portend what happens at a larger scale across Borneo. Fittingly, Sabah has committed large parts of its forest reserves to the Heart of Borneo initiative, a scheme pushed by WWF to protect and link remaining quality forest areas across the island (tellingly, Sarawak’s commitment is virtually nil) and there’s Forever Sabah, a grassroots push to transition Sabah toward a low carbon green economy which supporters hope will usher in smarter management of its resources. The question going forward however is whether there will still be enough to save across Borneo.

“We can’t do business-as-usual,” said Mannan. “We don’t have huge areas of virgin forest available for logging anymore.”

Imbak Canyon, Sabah. |

CITATIONS:

Related articles

In pictures: Rainforests to palm oil

(07/02/2012) In late May I had the opportunity to fly from Kota Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo to Imbak Canyon and back. These are some of my photos. Historically Borneo was covered by a range of habitats, including dense tropical rainforests, swampy peatlands, and natural grasslands. But its lowland forests have been aggressively logged for timber and then converted for oil palm plantations.