Logging in Gabon, Central Africa. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Industrial logging in primary tropical forests that is both sustainable and profitable is impossible, argues a new study in Bioscience, which finds that the ecology of tropical hardwoods makes logging with truly sustainable practices not only impractical, but completely unprofitable. Given this, the researchers recommend industrial logging subsidies be dropped from the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program. The study, which adds to the growing debate about the role of logging in tropical forests, counters recent research making the case that well-managed logging in old-growth rainforests could provide a “middle way” between conservation and outright conversion of forests to monocultures or pasture.

“We are facing a global biodiversity and a climate change crisis and we cannot afford to continue to lose primary tropical forests—they are central to resolving both crises,” authors Barbara Zimmerman with the International Conservation Fund for Canada and Cyril Kormos, Vice President for policy with the WILD Foundation, told mongabay.com. “Despite decades of trying to log sustainably, the rate of deforestation has barely dipped over the last 20 years, from 15 million hectares per year to 13 million hectares per year—and these are low estimates. Industrial logging has shown no capacity to keep forests standing. On the contrary, logging is usually the first step towards total clearing to make way for agricultural use.”

The study found that just three rounds of logging in tropical forests resulted in the near-extinction of target trees in all major rainforest zones—South and Central America, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia—resulting not only in ecological disturbance but economic fallout.

Ecological and economic barriers

Deforestation for palm oil in Sabah, Malaysia. Often logged forests are then converted to plantations or pastures. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

The very ecology of tropical rainforests—their rich biodiversity, unparalleled variety, and hugely complex interconnections between species—makes them particularly susceptible to disturbance. Targeting only a few key tree species in the forest, loggers quickly plunder these species while leaving the rest standing, rapidly changing the overall structure of the ecosystem. In this way, loggers undercut the very ecological system that allows their favored trees to replenish.

“Virtually all currently high-value timber species, are exceptionally long lived and slow growing, occur at low adult density, undergo high rates of seed and seedling mortality, sustain very sparse regeneration at the stand level, and rely on animal diversity for reproduction, all of which point to the conclusion that tropical trees probably need very large continuous areas of ecologically intact forest if they are to maintain viable population sizes,” Zimmerman and Kormos write in their paper.

The particular ecology of these trees has resulted in most logging companies simply entering a primary forest, cutting all high-value species, and then leaving it to colonizers or razing everything for cattle pasture or monoculture plantations (such as pulp and paper, rubber, or palm oil).

“Logging in the tropics follows the same economic model as is evident in most of the world’s ocean fisheries,” Zimmerman and Kormos write. “The most-valuable species are selectively harvested first, and when they are depleted, the next-most-valuable set is taken, until the forests are mined completely of their timber.”

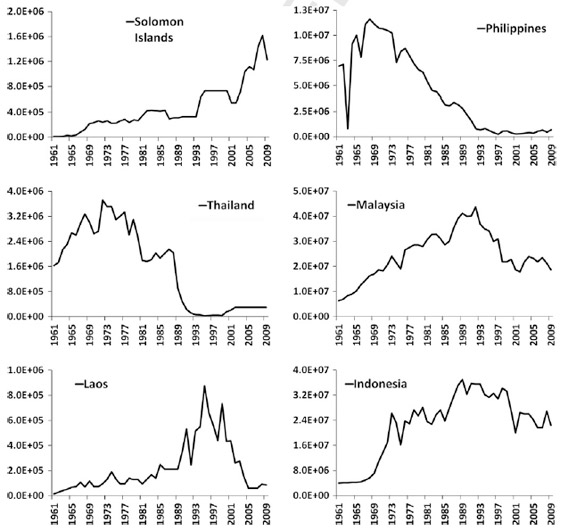

Boom and bust. Sawlog and veneer-log production for the Solomon Islands and five key South-East Asian nations (derived from FAOSTAT, 2011). Courtesy of Shearman et al 2012.

While initial logging can be quite profitable, later harvests bring in less-and-less money: fewer target trees can be found and the regenerative process for such species is compromised overall. Eventually industrial logging kills itself, leaving an economic vacuum that in accessible areas is often filled by conversion to pasture land, oil palm estates, industrial agriculture or timber plantations.

Some scientists have argued that the solution to this problem is to inject sustainable forest management practices into logging companies in the tropics. According to these sustainability proponents, this would ensure harvests over the long-term while protecting overall forest health.

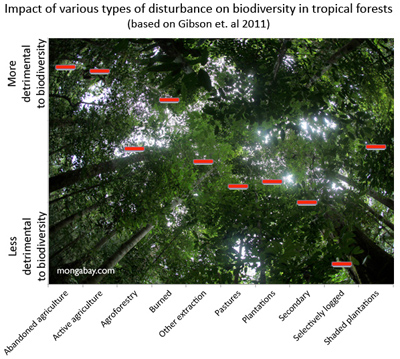

Impact of various disturbance regimes on biodiversity in tropical forests. Chart based on Gibson et. al 2011. Photo by Rhett Butler. Click to enlarge |

But according to their paper, even so-called reduced-impact logging—which is currently the exception rather than the norm in the tropics—considerably changes a forest’s ecology. With many of the forest’s vital seed and crop trees cut, Kormos and Zimmerman point out that “low-impact” logging leaves 20-50 percent of the canopy open, when “even small openings in the canopy (5-10 percent) can have significant impacts on the moisture content in the forest and increase risk of fire.” Debris left on the forest floor quickly dries out, creating perfect fodder for fire. Unlike temperate forests, fires in primary rainforests are almost unheard of, but low-impact logging creates a new set of ecological conditions that leave the forest vulnerable to heat, wind, and, yes, fire.

“We now know that under the present sustainable forestry management guidelines, tropical forests left to regenerate naturally will be composed largely of light-wooded tree species of no to low commercial value, whereas dense-wood, high-value timber species will experience severe population declines,” Kormos and Zimmerman write, noting that current guidelines are far too lax to keep forests intact.

Giant rainforest tree in Sumatra. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

True sustainability is not impossible to achieve, write Zimmerman and Kormos, but guidelines would need to be considerably toughened. Forestry companies would need to cut only every 60 years or more, harvest less than five trees per hectare, leave smaller logging gaps in the canopy, avoid cutting young trees, and use siliviculture techniques to plant new seedlings, among other considerations.

“The key to a forest’s ability to recover most of its original attributes after selective logging is low harvest intensity,” they write.

But, there is a reason why there are no industrial loggers in the tropics putting such stringent rules in place.

“The problem with implementing this kind of protocol is that it would substantially diminish harvestable timber volume while further increasing management and training costs, which would make the timber operation economically unviable,” Zimmerman and Kormos told mongabay.com.

It’s no wonder then that logging companies generally cut-and-run, a practice which has resulted in loggers moving from one untouched tropical forest to the next, always looking for the short-term gain. For example, after logging out most of the forests in Borneo, loggers moved into places like Sumatra. Now that Sumatra has been devastated—with many of its forests turned into monoculture plantations—industrial logging went to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Primary rainforest is vanishing worldwide.

Logging not a “middle way”

Zimmerman and Kormos’ paper is one among several that debates, sometimes heatedly, the role of logging in protecting or destroying tropical forests. For example, a paper in Conservation Letters recently came to a very different conclusion than Zimmerman and Kormos, describing well-managed logging as a middle way between conservation and outright destruction of tropical forests for agriculture or ranching.

“Selectively logged tropical forests, especially if they are logged gently and with care, retain most of their biodiversity and continue to provide ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and hydrological functions,” lead author of that study, Francis Putz with the University of Florida told mongabay.com in May.

Raw logs waiting for transport in Guyana. Photo by Jeremy Hance. |

Putz’s paper did not argue that logging had no impact, but rather that any impact from logging was far preferable than clearing a forest entirely. While Kormos and Zimmerman agree with this point, they see a different remedy.

“There is no question that industrial logging is better than cattle pastures or oil palm or other plantations—but the fact that industrial logging is better than total forest conversion doesn’t mean we should subsidize it,” Zimmerman and Kormos told mongabay.com. “Subsidies should be directed towards activities that maximize carbon, biodiversity and social benefits.”

They also say some of the paper’s findings are problematic. “The article includes introduced species in the biodiversity totals, and the biodiversity surveys cited were all done soon after logging and before a second harvest, so there would be an expectation that there would still be biodiversity left in the short term—the question is what happens to biodiversity in the medium term, in particular after a second harvest? In addition, the article states that a logged forest retains 76% of its carbon. But 24% of a forest’s carbon is a very substantial amount of carbon emissions—it could take several decades just to recapture that carbon, whereas we need to be maximizing forest carbon right now.”

Even more importantly, perhaps, is that economic problems remain, dooming many logged forests to total clearance.

“The ‘middle way’ does not make logging sustainable. The Putz et al article clearly acknowledges that the middle way does not achieve sustained timber yields. As a result, it does nothing to change the fundamental dynamic, which is that logging usually precedes conversion to higher value agriculture use. So the ‘middle way’ could actually make things worse—accelerating forest conversion,” Zimmerman and Kormos say.

REDD-out

|

Given the problems of balancing the ecology and economics of logging in tropical forests, Zimmerman and Kormos argue that the UN program, REDD+, should discontinue a component that would give money to industrial logging companies to manage rainforests for their carbon.

“REDD+ should not be used to subsidize industrial logging. The biodiversity and climate change crises are rapidly getting worse, and keeping primary forests intact is an essential part of the response to both crises. REDD funding should be reserved for activities that keep primary forests intact, such as community management and protected areas” Zimmernam and Kormos say. They note that REDD+, which is meant to pay countries to preserve forests as carbon reservoirs, would undercut its main goal, since even well-managed logging concessions lose significant carbon when trees are felled, especially large, old trees. In addition, logged forests are at significant risk of total carbon loss as a result of fire or conversion to agricultural use.

Still, Zimmerman and Kormos, say logging can occur in tropical forests, only it should be small operations run by local communities, and not the industrial logging that dominates the trade today.

“Community logging works when it is implemented at non-industrial scales by communities that have a vested interest in being good stewards of their land,” they say. The key here is that local communities govern their own forests, which takes away the cut-and-run problem. In addition, such programs must be supported by the national government. This is where REDD+ could really make a difference.

“The most important reason that these successful local-scale sustainable forestry management models have not been scaled up to secure the world’s remaining tropical forests is a lack of funding—-a situation that REDD+ investment might correct,” the authors note.

Gabon. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Zimmerman and Kormos say they would support a global moratorium on industrial logging in primary forests, an idea that has been floated in some environmental circles. Smaller-scale moratoriums are not unprecedented. Indonesia is currently attempting to implement a national moratorium, albeit the scheme is facing many difficulties and criticism both from environmentalists and industry. In addition, in 2002, the Democratic Republic of Congo instituted a moratorium on any new logging concessions being granted or renewed, although this moratorium has also suffered from widespread breaches. But if loggers are not to enter the world’s last primary tropical rainforests—those, at least, currently unprotected by parks—drastic changes would need to be made in forest governance, which currently favors big industrial logging conglomerates over local communities with a long-term stake in the health of their forest.

CITATIONS:

Pinard, Douglas Sheil, Jerome K. Vanclay, Plinio Sist, Sylvie Gourlet-Fleury, Bronson Griscom,

John Palmer and Roderick Zagt. Sustaining conservation values in selectively logged tropical forests: The

attained and the attainable. Conservation Letters. 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00242.x.

Related articles

Industrial logging leaves a poor legacy in Borneo’s rainforests

(07/17/2012) For most people “Borneo” conjures up an image of a wild and distant land of rainforests, exotic beasts, and nomadic tribes. But that place increasingly exists only in one’s imagination, for the forests of world’s third largest island have been rapidly and relentlessly logged, burned, and bulldozed in recent decades, leaving only a sliver of its once magnificent forests intact. Flying over Sabah, a Malaysian state that covers about 10 percent of Borneo, the damage is clear. Oil palm plantations have metastasized across the landscape. Where forest remains, it is usually degraded. Rivers flow brown with mud.

In pictures: Rainforests to palm oil

(07/02/2012) In late May I had the opportunity to fly from Kota Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo to Imbak Canyon and back. These are some of my photos. Historically Borneo was covered by a range of habitats, including dense tropical rainforests, swampy peatlands, and natural grasslands. But its lowland forests have been aggressively logged for timber and then converted for oil palm plantations.

Conservation areas failing to protect forests better than logging concessions in Sumatra

(06/28/2012) Areas zoned for conservation suffered deforestation rates similar to logging concessions in Sumatra between 1990 and 2000, but maintained forest cover more effectively than lands allocated for agricultural conversion, reports a study published in Conservation Letters.

Norway: Indonesia’s forest moratorium isn’t enough to meet emissions reduction target

(05/23/2012) Indonesia’s moratorium on new forest concessions will not be enough to meet its 2020 emissions reduction target says the largest backer of the country’s forest and climate action plan.

Can loggers be conservationists?

(05/10/2012) Last year researchers took the first ever publicly-released video of an African golden cat (Profelis aurata) in a Gabon rainforest. This beautiful, but elusive, feline was filmed sitting docilely for the camera and chasing a bat. The least-known of Africa’s wild cat species, the African golden cat has been difficult to study because it makes its home deep in the Congo rainforest. However, researchers didn’t capture the cat on video in an untrammeled, pristine forest, but in a well-managed logging concession by Precious Woods Inc., where scientist’s cameras also photographed gorillas, elephants, leopards, and duikers.

Big trees, like the old-growth forests they inhabit, are declining globally

(01/26/2012) Already on the decline worldwide, big trees face a dire future due to habitat fragmentation, selective harvesting by loggers, exotic invaders, and the effects of climate change, warns an article published this week in New Scientist magazine. Reviewing research from forests around the world, William F. Laurance, an ecologist at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, provides evidence of decline among the world’s ‘biggest and most magnificent’ trees and details the range of threats they face. He says their demise will have substantial impacts on biodiversity and forest ecology, while worsening climate change.

Logging of primary rainforests not ecologically sustainable, argue scientists

(01/25/2012) Tropical countries may face a risk of ‘peak timber’ as continued logging of rainforests exceeds the capacity of forests to regenerate timber stocks and substantially increases the risk of outright clearing for agricultural and industrial plantations, argues a trio of scientists writing in the journal Biological Conservation. The implications for climate, biodiversity, and local economies are substantial.

Old-growth forests are irreplaceable for sustaining biodiversity

(09/14/2011) Old growth rainforests should be a top conservation priority when it comes to protecting wildlife, reports a new comprehensive assessment published in the journal Nature. The research examined 138 scientific studies across 28 tropical countries. It found consistently that biodiversity level were substantially lower in disturbed forests.

Logged rainforests are a cheap conservation option

(09/14/2011) With old-growth forests fast diminishing and land prices surging across Southeast Asia due to rising returns from timber and agricultural commodities, opportunities to save some of the region’s rarest species seem to be dwindling. But a new paper, published in the journal Conservation Letters, highlights an often overlooked opportunity for conservation: selectively logged forests.

Indonesia’s moratorium undermines community forestry in favor of industrial interests

(06/21/2011) Indonesia’s moratorium on new concessions in primary forest areas and peatlands “completely ignores” the existence of community forestry management licenses, jeopardizing efforts to improve the sustainability of Indonesia’s forest sector and ensure benefits from forest use reach local people, say environmentalists. According to Greenomics-Indonesia, a Jakarta-based NGO, community and village forestry licenses are not among the many exemptions spelled under the presidential instruction that defines the moratorium. The instruction, issued last month, grants exemptions for industrial developers and allows business-as-usual in secondary forest areas by the pulp and paper, mining and palm oil industries.

Loss of old growth forest continues

(10/06/2010) A new global assessment of forest stocks by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) shows continuing loss of primary forests since 2005 despite gains in the extent of protected areas. FAO’s Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010 reveals some 13 million hectares of forest were cleared between 2000 and 2010, down from around 16 million hectares per year during the 1990s. Loss of primary forest—mostly a consequence of logging—averaged 4.2 million hectares per year, down from 4.7 million hectares per year in the 1990s.

Timber certification is not enough to save rainforests

(06/02/2010) In the 1980s and 1990s pressure from activist groups led some of the world’s largest forestry products companies and retailers to join forces with environmentalists to form the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a certification standard that aims to reduce the environmental impact of wood and paper production on natural forests. Despite initial skepticism on whether buyers would pay a premium for greener forest products, FSC quickly grew and by 2000 had become a standard in many markets, including Europe and the United States. Companies like Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Ikea are today strong supporters of the FSC. But the FSC has not been without controversy. In recent years some activists have voiced concern about FSC standards as well as the credibility of auditors that certify timber operations. Among the initiative’s supporters is the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), a group best known for its aggressive protest tactics. RAN says engagement with the FSC is better than the alternative: leaving the timber industry to devise its own sustainability standards.

Destruction of old-growth forests looms over climate talks

(12/08/2009) Destruction of old-growth or primary forests looms large in discussions in Copenhagen over a scheme to compensate tropical countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD). Some environmental groups are pressing for conservation of old-growth forests — the most carbon-dense, and biologically-rich state of forests — to be the centerpiece of REDD, while industry and other actors are pushing for “sustainable forest management” or logging using reduced-impact techniques to be the primary focus of REDD.

Rainforest conversion to oil palm causes 83% of wildlife to disappear

(09/15/2008) Conversion of primary rainforest to an oil palm plantation results in a loss of more than 80 percent of species, reports a new comprehensive review of the impacts of growing palm oil production. The research is published in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

In the Amazon, primary forest biodiversity tops that of secondary forest, plantations

(11/12/2007) Plantations and secondary forests are no match for primary Amazon rainforest in terms of biodiversity, reports the largest ever assessment of the biodiversity conservation value in the tropics.