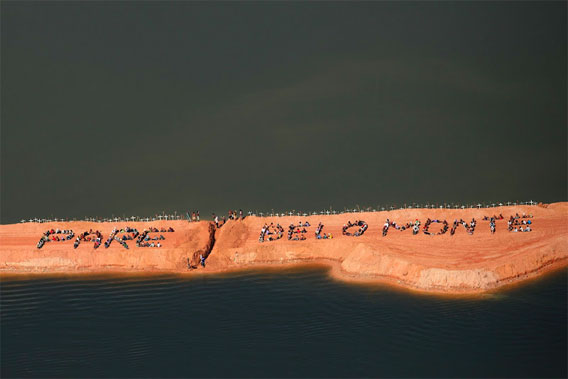

Belo Monte protest. Photo credit: Atossa Soltani/ Amazon Watch / Spectral Q.

Brazil’s ambitious plans to build 30 dams in the Amazon basin could trump the country’s efforts to protect the world’s largest rainforest, said a leading Amazon scientist speaking at the annual meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) in Bonito, Brazil.

Philip Fearnside of Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia in Manaus, warned that contrary to claims put forth by proponents, dams in the Amazon aren’t a source of green energy. Nor do they offer good returns for the tens of billions of dollars that will need to be invested.

“Dams are a centerpiece of greenwashing here in the Amazon,” he said during a symposium on changing drivers of deforestation organized by mongabay.com.

“Dams release methane, a gas with a much higher impact on global warming per ton than carbon dioxide, especially during the first decades after construction. These emissions are often even higher than those of generating electricity from fossil fuels for decades, thus corresponding to the narrow time interval when global warming must be brought under control to avoid massive impacts, including those in Amazon forest.”

Dams in the tropics have two principle greenhouse gas emissions sources: carbon released from soil carbon stocks and dying vegetation when the reservoir is flooded and methane formed where organic matter decays under low oxygen conditions at the bottom of the reservoir. Methane emissions are facilitated by a dam’s turbines, which usually draw from the bottom of the reservoir and spray methane-dense water into the air upon release. Emissions from rotting vegetation occur on an ongoing basis when the levels of the reservoir fluctuate: during the dry season weeds, emerge from the muddy drop-down zone, only to rot again when waters return. The effect turns a typical tropical dam into a “methane factory”, according to Fearnside.

Planned dams in Brazil. Courtesy of Dams in the Amazon.

Dams in the Amazon are also enablers of deforestation, spawning roads that facilitate new clearing and generating electricity for industrial farms, mines, and aluminum manufacturing.

“80 percent of the value of aluminum is electricity,” said Fearnside. “Brazil is effectively exporting energy in the form of aluminum.”

He noted that aluminum factories generate only 2.7 jobs per gigawatt of electricity, which he deemed a “very poor return” given the costs, which include disrupting fish migration patterns and displacing tens of thousands of people, including indigenous communities.

“Since the traditional human population in Amazonia lives along the rivers (including both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples), these dams imply expelling almost all of this population.”

Construction site of the Belo Monte Dam and hydropower project, near Altamira. Photo by © Greenpeace/Marizilda Cruppe. |

Fearnside said the controversial Belo Monte dam on the Xingu River in the state of Pará illustrated many of the concerns with dam-building in the Amazon. The dam will flood a quarter of the city of Altamira and divert 80 percent of the Xingu’s flow from the main stem of the river, leaving 60 miles (100 km) of one of the Amazon’s largest tributaries nearly dry. Communities of that stretch of the river will lose their primary source of livelihoods — fishing. The dam will also impede migration of some of the river’s largest fish species, potentially affecting fish populations elsewhere in the river basin. Other communities will suffer from inundation. In these areas, people are being removed by force, according to Fearnside.

But the dam has bigger problems. As currently designed, Belo Monte will suffer from the Xingu’s seasonal variation in water flows. The most expensive parts of the dam to operate — turbines and transmission lines — would need to be idled for four months each year due to low water. That issue makes it likely that Brazil will push forth with a plan to build additional dams upstream from Belo Monte (up to six dams were planned on the Xingu until 2008). These dams would capture water, ensuring more consistent flow for Belo Monte. However greater water level fluctuation upstream means these dams will have even higher methane emissions relative to their generating capacity.

Construction of a canal for the Belo Monte Dam project, near Altamira taken by Daniel Beltrá for Greenpeace. Once completed, the Belo Monte Dam will be the third largest in the world. It will submerge up to 400,000 hectares and displace 20,000 people. Image © Daniel Beltrá / Greenpeace.

Fearnside concluded his talk with a call for smarter energy use and production in Brazil.

“Fortunately, Brazil has many other options for meeting its electricity needs without the planned hydroelectric advance in Amazonia,” he said. “Brazil’s export of electricity in the form of electro-intensive products such as aluminum is rapidly increasing. Just halting aluminum exports would represent more than the generation of the notorious Belo Monte Dam.”

He cited Brazil’s inefficient use of electric showerheads, which consume 5 percent of electricity nationwide, as an opportunity for efficiency gains.

“Energy conservation would also avoid dams: just replacing electric showerheads with solar water heating would save much more than what would be generated by Belo Monte.”

He added that Brazil has “tremendous potential” for wind and solar power, “which do not receive the massive government investments that are going into dams.”

Fearnside also urged a rethink of Brazil’s energy policy.

“A through and democratic national discussion of energy policy is needed before dam proposals are announced,” he said.

“The environmental and social impact of proposed dam projects need to be evaluated in an unbiased and transparent way with full input from the scientific community and other parts of civil society. Licensing procedures need to be strengthened rather than weakened and abbreviated, as is the current trend.”

“Recent shortcuts in the licensing of the Belo Monte and Madeira River Dams provide unfortunate precedents and underline the urgency of rethinking energy policy and the dam-building decision process.”

Related articles