Researchers say restoring seagrass beds would mitigate climate change.

Mangroves above and seagrass below in Vohemar Bay, Madagascar. Photo: © Keith Ellenbogen/iLCP.

Just below the ocean’s surface lies a carbon powerhouse: seagrass meadows. New research in Nature Geoscience estimates that the world’s seagrass meadows conservatively store 19.9 billion metric tons of carbon, even though the threatened marine ecosystems make up only 0.2 percent of Earth’s surface. The findings lend support to the idea that seagrass protection and restoration could play a major role in mitigating climate change.

“One remarkable thing about seagrass meadows is that, if restored, they can effectively and rapidly sequester carbon and reestablish lost carbon sinks,” study coauthor Karen McGlathery with the University of Virginia said in a press release.

Examining nearly a thousand seagrass meadows worldwide, the study found that the ecosystem are capable of storing around 83,000 metric tons of carbon per square kilometer. This is over double what an average forest stores: on average 30,000 metric tons per square kilometers. Storing carbon deep in their soils, the researchers say seagrass meadows likely sequester 10 percent of the carbon in the world’s oceans.

“Seagrasses have the unique ability to continue to store carbon in their roots and soil in coastal seas. We found instances where particular seagrass beds have been storing carbon for thousands of years,” explains James Fourqurean, lead author and researcher with the Florida International University and the Blue Carbon Initiative.

Seagrass beds have long been recognized as providing crucial ecosystem services such as habitat and nurseries for many marine species, mitigation of pollution, and alterations in water flow, yet these precious meadows continue to be lost. According to the study, almost one third of all seagrass meadows have been destroyed by dredging, degradation of water quality, and coastal development. Currently at least 1.5 percent of seagrass meadows are lost annually, producing carbon emissions that could equal a quarter of those stemming from global deforestation.

A study in 2009 estimated that 58 percent of the world’s seagrass meadows were in decline.

Given this, the scientists say the world should prioritize conservation efforts, while working to restore degraded and vanished seagrass meadows.

“Our vital seagrass ecosystems have always been a conservation priority, given their myriad benefits of ecosystem services to local communities,” said Emily Pidgeon, co-chair of the Blue Carbon Initiative and senior director of Strategic Marine Initiatives at Conservation International (CI). “Now we must also recognize the vital importance of coastal ‘blue’ carbon ecosystems, such as seagrass meadows, for their importance to global climate health.”

A green turtle (Chelonia mydas) grazes on seagrass in Brazil’s Abrolhos region. Photo: © Luciano Candisani/iLCP.

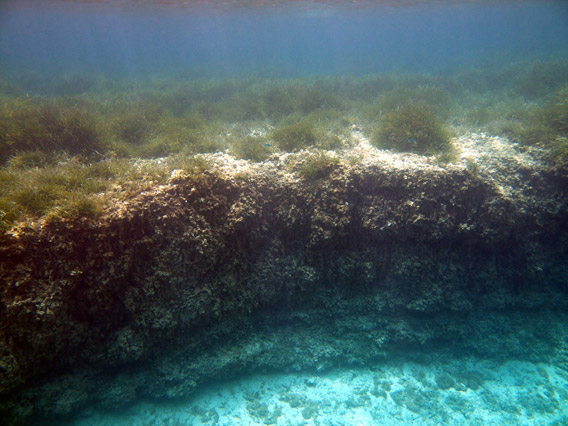

A peat-like deposit of dead belowground parts of the plant accumulated during 1,200 years. Usually thisis called Mat or Matte. This particular mat accretes about 80gC/m2/yr. Photo: © Miguel Angel Mateo.

CITATION: James W. Fourqurean,

Carlos M. Duarte,

Hilary Kennedy,

Núria Marbà,

Marianne Holmer,

Miguel Angel Mateo,

Eugenia T. Apostolaki,

Gary A. Kendrick,

Dorte Krause-Jensen,

Karen J. McGlathery

& Oscar Serrano. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nature Geoscience. 2012. doi:10.1038/ngeo1477.

Related articles

Tar sands emit more carbon than previously estimated

(03/12/2012) Environmentalists have targeted the oil-producing tar sands in Canada in part because its crude comes with heftier carbon emissions than conventional sources. Now, a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) has found an additional source of carbon that has been unaccounted for: peatlands. Mining the oil in the tar sands, dubbed “oil sands” by the industry, will require the wholesale destruction of nearly 30,000 hectares of peatlands, emitting between 11.4 and 47.3 million metric tons of additional carbon.

Bad feedback loop: climate change diminishing Canadian forest’s carbon sink

(01/30/2012) Climate change, in the form of rising temperatures and less precipitation, is shrinking the carbon sink of western Canada’s forest, according to a new study released today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Tree mortality and a general loss of biomass has cut the carbon storage capacity of Canada’s boreal forests by around 7.28 million tons of carbon annually, equal to nearly 4 percent of Canada’s total yearly carbon emissions.

Protecting original wetlands far preferable to restoration

(01/26/2012) Even after 100 years have passed a restored wetland may not reach the state of its former glory. A new study in the open access journal PLoS Biology finds that restored wetlands may take centuries to recover the biodiversity and carbon sequestration of original wetlands, if they ever do. The study questions laws, such as in the U.S., which allow the destruction of an original wetland so long as a similar wetland is restored elsewhere.

Critically Endangered lemurs disperse seeds, store carbon

(11/13/2011) Many tropical plants depend on other species to carry their progeny far-and-wide. Scientists are just beginning to unravel this phenomenon, known as seed dispersal, which is instrumental in supporting the diversity and richness of tropical forests. Researchers have identified a number of animal seed dispersers including birds, rodents, monkeys, elephants, and even fish. Now a new study in the Journal of Tropical Ecology adds another seed disperser to that list: the Critically Endangered black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata). Capable of dispersing big tree species, the black-and-white ruffed lemur may even play a big role in carbon sequestration.

Atlantic Forest stores less carbon due to drastic fragmentation

(09/26/2011) The Atlantic Forest in Brazil is one of the most fragmented and damaged forests in the world. Currently around 12 percent of the forest survives, with much of it in small fragments, many less than 100 hectares. A new study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science finds that the bloodied nature of the Atlantic Forest impacts its capacity to sequester carbon. The study found that 92 percent of the forest stored only half its potential carbon due to fragmentation and edge-effects, which includes damage due to winds and exposure to drought.