Forest clearing in the Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Indigenous populations in the Amazon successfully farmed without the use of fire before the arrival of Europeans, demonstrating a potentially sustainable approach to land management in a region that is increasingly vulnerable to man-made fires.

The research, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, builds on a growing body of evidence showing that pre-Columbian societies practiced advanced farming techniques that were less damaging to the environment than present-day approaches.

“This ancient, time-tested, fire-free land use could pave the way for the modern implementation of raised-bed agriculture in rural areas of Amazonia,” said the study’s lead author José Iriarte of the University of Exeter, in a statement. “Intensive raised-field agriculture can become an alternative to burning down tropical forest for slash and burn agriculture by reclaiming otherwise abandoned and new savannah ecosystems created by deforestation. It has the capability of helping curb carbon emissions and at the same time provide food security for the more vulnerable and poorest rural populations.”

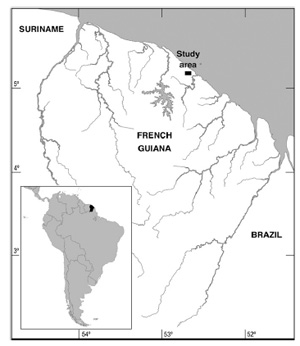

Research site. Courtesy of Iriarte et al/PNAS. |

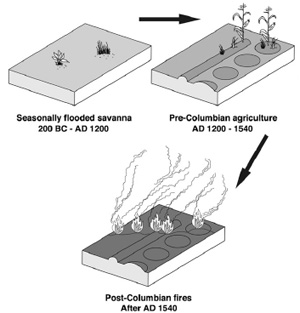

The conclusions are based on analysis of pollen records, charcoal deposits, and other plant remains from soil layers representing a 2,000-year period ending some 800 years ago. The research, which took place in natural savannas in French Guiana, shows that ancient Amazonian populations utilized raised-bed farming, where crops were planted in mounds to protect against flooding and improve soil fertility. Farmers limited the incidence of fire, according to the study.

The findings contrast with the conventionally held belief that native populations relied on fire to convert forest to savanna, as is typically done in the Amazon today.

“Our results force reconsideration of the long-held view that fires were a pervasive feature of Amazonian savannas,” said co-author Mitchell Power of the University of Utah.

In fact, the mass death of the indigenous population following the European invasion of the New World may have reduced the long-term productivity of the land.

Schematic drawing of changing vegetation and disturbance regimes as inferred from analysis of pollen, phytoliths, and charcoal from the K-VIII core. Image and caption courtesy of Iriarte et al/PNAS. |

“These raised-field systems can be as productive as the man-made black soils of the Amazon, but with the added benefit of low carbon emissions,” added Stephen Rostain of Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, referring to rich soils discovered in other parts of the Amazon. These black soils or “terra preta” were formed by an indigenous biochar process that converted poor rainforest dirt into intensely fertile soil. Researchers are now trying to unlock that process to boost the productivity of tropical soils.

At the same time scientists are warning that current practices are putting the Amazon ecosystem at risk. A combination of climate change, selective logging, and deforestation are boosting the Amazon’s vulnerability to drought, which turns areas of rainforest usually too wet to burn into tinder for fires that escape from neighboring pasture and agricultural lands. Amazon fires not only cause local pollution and health impacts — they are an important contributor to climate change. Therefore the ancient “no-burn” system could yield environmental dividends.

“Whereas savannas today are often associated with frequent fire and high carbon emissions, our results show that this was not always so,” said Doyle McKey of the University of Montpellier. “With global warming, it is more important than ever before that we find a sustainable way to manage savannas. The clues to how to achieve this could be in the 2,000 years of history that we have unlocked.”

CITATION: José Iriarte et al (2012). Fire-free land use in pre-1492 Amazonian savannas. PNAS April 13. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1201461109

Related articles

Pre-Colombian Amazonians lived in sustainable ‘urban’ society

(08/28/2008) Researchers have uncovered new evidence to support the controversial theory that parts of the Amazon were home to dense “urban” settlements prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 15th century. The study is published this Friday in the journal Science. Conducting archeological excavations and aerial imagery across a number of sites in the Upper Xingu region of the Brazilian Amazon, a team of researchers led by Michael Heckenberger found evidence of a grid-like pattern of 150-acre towns and smaller villages, connected by complex road networks and arranged around large plazas where public rituals would take place. The authors argue that the discoveries indicate parts of the Amazon supported “urban” societies based around agriculture, forest management, and fish farming.

Ancient Amazon fires linked to human populations

(02/20/2008) Analysis of soil charcoal in South America confirms that from a historical perspective, fire is rare in the Amazon rainforest, but when it does occur, it appears linked to human activities. The research, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, is based on dating of soil carbon, which provides a good indication of when fires occurred in Amazonia, according to lead author Mark Bush, head of the Department of Biology at Florida Institute of Technology.

Ancient Amazonian technology could save the world

(05/17/2007) Terra preta, the ancient charcoal-based soil used by ancient Amazonians to create permanently fertile agricultural lands in the rainforest, is getting serious consideration as a means to fight global warming and meet domestic energy demand, reports an article in Scientific American.

Pre-Columbian Amazon supported millions of people

(10/18/2005) Controversial evidence uncovered over the past decade suggests that the Amazon rainforest was once home to large sedentary populations of people. Besides the well-known empires of the Inca and their predecessors, the Huari, millions of people once lived in the forests and shaped the environment to suit their own needs.