Oil palm and logged over rainforest in Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler 2008.

Unilever is in talks to build a $130 million palm oil processing mill in Indonesia as part of its commitment to use more environmentally-friendly palm oil in its products, reports The Wall Street Journal.

The mill, which would be located in Sumatra, would produce about 10 percent of Unilever’s annual consumption of palm oil, which is produced from fruit from the oil palm tree. Unilever is the world’s largest single consumer of palm oil, using 1.36 million tons a year for beauty and food products, including Dove soap, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, and Vasoline.

The processing plant would churn out palm-kernel oil derived only from plantations certified under sustainability standards set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). These include provisions for reducing pollution and avoiding deforestation in sensitive areas, among others.

The company disclosed it will reach its target of 100 percent certified sustainable palm oil covered by GreenPalm certificates by the end of 2012, three years ahead of schedule. GreenPalm certificates, which represent physical palm oil certified under the RSPO, allows companies to bypass supply-chain complexities and financially support sustainable palm oil even if their actual sources are not sustainably certified.

Oil palm plantations and forest. Courtesy of Google Earth. |

Unilever also announced a new goal to purchase 100 percent of its palm oil from certified traceable sources by 2020, a target that sets a new bar for major palm oil buyers, which until now had mostly limited commitments to 100 percent RSPO-certified palm oil by 2015. Unilever said the traceability standard “means it will be able to track all the certified oil it buys back to the plantation on which it was originally grown.”

Some critics of the RSPO have argued that the standard — as currently constructed — allows producers to claim they are producing sustainable palm oil when in fact they have only paid a membership fee to the body. Unilever’s traceability commitment would weed out such suppliers and provide assurances to consumers that any palm oil in Unilever products was produced in a manner that met environmental and social criteria. In 2011 27,000 tons of palm oil used by Unilever came from traceable sources, while another 803,000 tons was covered by GreenPalm certificates.

Unilever’s announcement came the same day that Cargill responded to criticism from the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), an environmental activist group that has targeted the agricultural giant for its palm oil sourcing policies. RAN says Cargill’s “lack of safeguards” for palm oil make it complicit in the destruction of Indonesia’s rainforests [PDF], including an area of orangutan habitat in Tripa, on the island of Sumatra, which has made headlines in recent weeks.

“Cargill has no safeguards on its global palm oil supply chain,” said RAN in a statement issued Tuesday. “Without such safeguards Cargill cannot ensure it is not contributing to egregious violations like the one underway in Tripa peat forest of Indonesia.”

Cargill maintains it is “committed to sourcing its palm oil products responsibly.”

Where forest once stood in Sumatra. |

“Last year, 94% of the of the crude palm oil Cargill sourced from Indonesia oil palm plantations was from RSPO members,” a Cargill spokesperson told mongabay.com. “Cargill continues to work with oil palm smallholders to help them sustainably increase their yields and move towards RSPO certification.”

But RAN says Cargill isn’t doing enough to ensure its palm oil isn’t sourced from places like Tripa.

“RSPO membership does not ensure that any RSPO criteria are being met at the plantation level since the only major criteria to meet in the first 5 years is consistent dues payment,” RAN Forest Campaigner Lindsey Allen told mongabay.com. “Cargill fails to have safeguards on the palm oil they trade that would ensure to customers they are not sourcing from Tripa.”

RAN is asking Cargill to adopt “a comprehensive set of safeguards on the palm oil they trade” and be “open and transparent” about the companies that supply it with palm oil. In other words, a traceability standard.

The palm oil debate

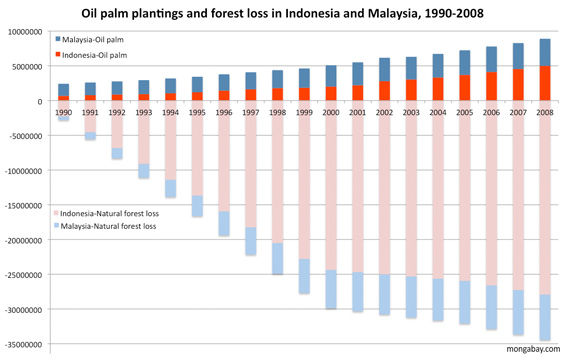

While palm oil is a highly productive crop, yielding more oil per unit of area than any other oilseed, it has come under fire because its production has taken a heavy toll on wildlife-rich rainforests and carbon-dense peat swamps in Indonesia and Malaysia, including key habitat for endangered orangutans, elephants, tigers, and rhinos. Some plantations have also been associated with forced displacement of communities, social conflict, and labor abuses.

The industry maintains its crop is a cheap source of cooking oil and has raised standards of living in poor rural areas.

Palm oil production has rapidly expanded in recent decades due to rising affluence and its growing use as an ingredient in processed foods. Up to 50 percent of packaged food products in some markets now contain palm oil. These products — and the companies that sell them — are now targets for campaigners seeking to reform production practices. Unilever’s targets for more sustainable palm oil are a direct consequence pressure from Greenpeace during a colorful 2008 campaign which included activists dressed up as orangutans invading the company’s shareholder meeting.

“Greenpeace was right to attack us,” Gavin Neath, Senior Vice President for Sustainability at Unilever, said during a panel last month at the Skoll World Forum. “We felt we were being conscientious and were doing more than others but we were not moving nearly fast enough. Greenpeace triggered us into action.”

Related articles

Green groups may call for boycott of Indonesian palm oil over forest destruction in Sumatra

(04/11/2012) Environmental groups are escalating their battle over an area of peat forest in Tripa, Sumatra that has been granted for oil palm plantations.

Certified palm oil profitable for companies, finds study

(04/06/2012) A new study suggests shifting to certified palm oil production increases profitability despite higher production costs.

RSPO-certified palm oil production jumps, generates $21M in premiums for producers

(03/08/2012) Production and sales of palm oil certified under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) reached record volume in 2011, reports a new analysis published by the multistakeholder body.

Cargill should do more to end use of problematic palm oil, says RAN

(11/24/2011) As part of our coverage of the 9th Annual Roundtable Meeting on Sustainable Palm Oil currently underway in Kota Kinabalu in Sabah, Malaysia, mongabay.com is interviewing participants and attendees. In the following interview, mongabay.com speaks with the delegation from the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), an advocacy group which has been critical of some Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) members for what is sees as ongoing social and environmental problems.

Is Indonesia losing its most valuable assets?

(05/16/2011) Deep in the rainforests of Malaysian Borneo in the late 1980s, researchers made an incredible discovery: the bark of a species of peat swamp tree yielded an extract with potent anti-HIV activity. An anti-HIV drug made from the compound is now nearing clinical trials. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and help improve the lives of millions of people. This story is significant for Indonesia because its forests house a similar species. In fact, Indonesia’s forests probably contain many other potentially valuable species, although our understanding of these is poor. Given Indonesia’s biological richness — Indonesia has the highest number of plant and animal species of any country on the planet — shouldn’t policymakers and businesses be giving priority to protecting and understanding rainforests, peatlands, mountains, coral reefs, and mangrove ecosystems, rather than destroying them for commodities?

A new front in the war over palm oil?

(05/09/2011) A new study for the U.K. government found that in 2009 Britain imported at least 1.65 million metric tons of palm oil-related products for production of food, fuel, and cosmetics. Notably, the DEFRA study concluded Britain’s consumption of palm kernel — typically considered a byproduct of palm oil production — was actually higher than its palm oil demand and accounted for roughly 10 percent of global palm kernel output.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.