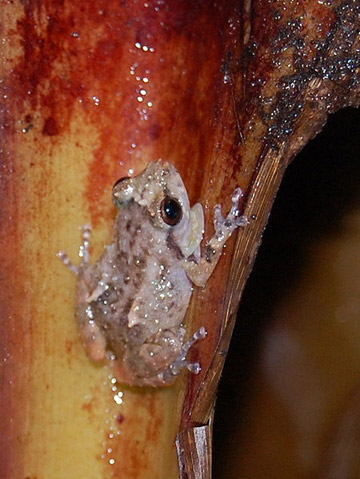

Given their often tiny size and cryptic nature, how does one determine frog populations in the rainforest? Just eavesdrop. A new study in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Society (TCS) employed automated recorders to listen to amphibian calls to determine if the common tink frog (Diasporus diastema) could be found in recovering secondary forests in Costa Rica.

“[The common tink frog’s] small size and its preference for calling from hidden sites make it difficult to observe in the field. In contrast, its ‘tink’ call is loud and easily differentiated from other species,” the researchers write.

A brown bear in Alaska. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Gathering 49,273 recordings from 12 secondary forests and 3 primary forests, the researchers noted the tink frog’s distinct call in about 21 percent of the total recordings (10,605). Surprisingly, they found no change in the number of tink frog’s calls in primary forest over secondary forest.

“Given that the secondary forests were abandoned pastures, and [the tink frog] has been reported as a forest species, it appears that the species has recovered rapidly in these sites,” the researchers write. Their study contrasts with earlier research that failed to find the tink frog in secondary forest, however the scientists note that in the previous study “a large river separated the mature and secondary forest, which may have limited colonization.”

The scientists did find that calling changed depending on the season and time. Peak calling occurred from 10 PM to 1 AM, and calling was very low during the dry season.

The researchers conclude that “given the extent of amphibian decline, there is a small glimpse of hope that these secondary forests can help maintain populations of this and other amphibians.”

CITATION: Hilje, B. and Aide, T. M. 2012. Calling activity of the common tink frog (Diasporus diastema) (Eleutherodactylidae) in secondary forests of the Caribbean of Costa Rica. Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 5(1):25-37.

Related articles

World’s most toxic frog gets new reserve

(03/05/2012) Touching a wild golden poison frog could kill you within minutes: in fact, a single golden poison frog, whose Latin name Phyllobates terribilis is even more evocative than its common one, is capable of killing 10 humans with its one milligram dose of poison. Yet the deadly nature of this tiny frog has not stopped it from nearing extinction. Now, in a bid to save the species, the World Land Trust (WLT) and Colombian NGO ProAves have teamed up to establish a 50 hectare (124 acres) reserve in the Chocó rainforest.

Vampire and bird frogs: discovering new amphibians in Southeast Asia’s threatened forests

(02/06/2012) In 2009 researchers discovered 19,232 species new to science, most of these were plants and insects, but 148 were amphibians. Even as amphibians face unprecedented challenges—habitat loss, pollution, overharvesting, climate change, and a lethal disease called chytridiomycosis that has pushed a number of species to extinction—new amphibians are still being uncovered at surprising rates. One of the major hotspots for finding new amphibians is the dwindling tropical forests of Southeast Asia.

Frog perfume? Madagascar frogs communicate via airborne pheromones

(01/25/2012) Researchers have found that some frogs in Madagascar communicate by more than just sound and sight: they create distinct airborne pheromones, which are secreted chemicals used for communicating with others. A paper published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition relates that some male members of the Mantellinae family in Madagascar use large glands on their inner thighs to produce airborne pheromones. Interestingly, the pheromones are structurally similar to those produced by insects. Scientists have identified frogs producing water-borne pheromones before, but this is the first instance of airborne.