This article is available for a limited time on mongabay.com. It has also been published in a book by mongabay journalist, Jeremy Hance: Life is Good: Conservation in an Age of Mass Extinction. The book is also available in Europe.

This is an expanded version of an article that ran on Yale e360 on December 5th, 2011: Camera Traps Emerge as Key Tool in Wildlife Research.

A camera trap sits precariously between two forest elephants. Photo courtesy of Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

I must confess to a recent addiction: camera trap photos. When the Smithsonian released 202,000 camera trap photos to the public online, I couldn’t help but spend hours transfixed by the private world of animals. There was the golden snub-monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana), with its unmistakably blue face staring straight at you, captured on a trail in the mountains of China. Or a southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla), a tree anteater that resembles a living Muppet, poking its nose in the leaf litter as sunlight plays on its head in the Peruvian Amazon. Or the dim body of a spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) led by jewel-like eyes in the Tanzanian night. Or the less exotic red fox (Vulpes vulpes) which admittedly appears much more exotic when shot in China in the midst of a snowstorm. Even the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), an animal I too often connect with cartoons and stuffed animals, looks wholly real and wild when captured by camera trap: no longer a symbol or even a pudgy bear at the zoo, but a true animal with its own inner, mysterious life.

Although the majority of camera trap photos are bleary, fuzzy or simply show parts of an animal rather than the whole, some camera trap photos are on a par with the best in wildlife photography, capturing one thing that is truly difficult for photographers: a palpable sense of intimacy.

This essay is published in Jeremy Hance’s new book: Life is Good: Conservation in an Age of Mass Extinction. Click to see in Amazon. Book is also available on Kindle and at Amazon.co.uk. |

But as mesmerizing as camera photos are, they serve a purpose beyond the aesthetic. It’s safe to say that the humble camera trap has revolutionized wildlife research and conservation: this simple contraption—an automated digital camera that takes a flash photo whenever an animal triggers an infrared sensor—has allowed scientists to collect photographic evidence of rarely seen, often globally endangered species, with little expense and relative ease, at least compared to tromping through tropical forests and swamps looking for endangered-rhino scat.

Researchers have used camera traps to document wildlife presence, abundance, and population changes, illustrating never-before-seen behavior and in a few cases catching unknown species. Camera traps are also beginning to be used to raise conservation awareness worldwide. What better way to connect the public to little-seen animals than with wild photos?

It must be noted that camera trapping is not new. The first cameras to capture wildlife free from human presence were taken by photographic pioneer George Shiras in the 1890s. Shiras used trip wires and a flash bulb to catch his animals on film, photos which were eventually published in National Geographic. The first purely scientific use of camera traps was in the 1920s when Frank Chapman surveyed the big species on Barro Colorado Island in Panama using the trip-wire camera trap, dubbing it a “census of the living.” However, technological difficulties, including battery power, size of equipment, and the trip mechanism, left camera trapping for intrepid enthusiasts and not mainstream researchers for decades. Not until the 1990s did a camera with an infrared trigger mechanism become available, and today with the advent of digital cameras, including video, the practice of studying wildlife through camera-trapping has exploded.

Camera trap photo of the Endangered pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis), Sapo National Park, Liberia. This is the first photo captured of a wild pygmy hippo in Liberia. © Ben Collen/ZSL/FFI/FDA. |

The use of camera traps has led to a huge number of discoveries in the wild kingdom, among them documenting an Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) in China for the first time in 62 years; proving that the world’s rarest rhino, the Javan (Rhinoceros sondaicus), is breeding, with a photo of a pregnant female; rediscovering the hairy-nosed otter (Lutra sumatrana) in the Malaysian state of Sabah; recording the first wolverine (Gulo gulo) in California since 1922; taking the first video of a bay cat (Pardofelis badia); documenting the incredibly elusive short-eared dog (Atelocynus microtis) preying on a caecillian in the Amazon; proving the incredibly rare Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) still inhabits Cambodia, and snapping the first ever photographs of a number of species in the wild, including Lowe’s servaline genet (Genetta servalina lowei), the Saharan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus hecki), the giant muntjac (Muntiacus vuquangensis), and the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis).

The technology was even behind the discovery of a few new species. Both the Annamite striped rabbit (Nesolagus timminsi) of Southeast Asia and the grey-faced sengi (Rhynchocyon udzungwensis) of Tanzania, the world’s largest sengi (otherwise known as elephants shrews), were first found via camera trap photos. Bizarrely enough, sengis seem uniquely attracted to this remote limelight: in northern Kenya a camera trap has also gathered the first evidence of what is likely another new species of sengi.

More discoveries are expected as researchers undertake new and larger initiatives, including a study of tropical mammals in seven nations by The Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring Network (TEAM), a video initiative to document the elusive wildlife of Sumatra, and a recent research program that will take camera traps as far as Antarctica.

What’s out there?

.568.jpg)

A Malay civet (Viverra-tangalunga) gets close to a camera trap in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions.

There is simply no tool better for finding out “what’s out there” than the camera trap. Within a few months of setting up traps, researchers can start to have a good sense of what large and medium-sized fauna reside in the area while conservationists can convey accurately what’s at stake.

On the island of Borneo, Brent Loken, Executive Director with conservation NGO Ethical Expeditions, has been working to collect data on the mammals of Wehea Forest in the Indonesia state of Kalimantan.

“Camera trapping provides a window into a world that was previously only accessible to researchers or individuals with intimate knowledge of that species or habitat,” Loken says, adding that the Internet has drastically changed society’s access to such photos.

“YouTube is providing a method of sharing this information with the world. Recent videos posted to YouTube of Amur leopards from the Russian Far East, snow leopards from Afghanistan or tigers from Sumatra have provided opportunities for individuals to learn about rare and endangered animals.”

.360.jpg) Sun bear in Wehea Forest. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions. |

Ethical Expeditions had a simple goal for its camera trap initiative: “to document as many different mammal species as possible in Wehea Forest.” Along with camera-trapping the group also surveyed on foot, netted bats, and caught small mammals. In total, they documented 50 mammal species to date—nearly a quarter of the mammals found in the U.S. in a forest smaller than Barbados.

Loken says that camera traps have been especially important in Wehea Forest for proving the existence of elusive mammals.

“Without camera traps, we would not have been able to document species such as the binturong, banded civet, yellow-throated marten, clouded leopard and sun bear to name a few. Camera trapping is also giving us insights into the density and abundance of the Sunda clouded leopard, one of the least known cat species in the world.”

For the first time many researchers are also getting baseline population data on tropical mammals and birds where only estimates, and often just guesses, were possible before.

“New data analysis methods provide researchers the tools to estimate abundances and densities for elusive species, something that was extremely difficult to determine only a few years ago,” Loken explains.

Once a baseline is established, subsequent camera trap programs can help decipher how populations are changing in the face of human pressures.

“As forests are lost at record pace, it is imperative to gain a better understanding of the ecological requirements of endangered animals such as the clouded leopard and how distribution and abundance may be affected by habitat disturbance,” Loken says.

.360.jpg) A troupe of maroon langurs (Presbytis-rubicunda). Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions. |

For Ethical Expeditions, camera trapping went beyond documenting animals: the group is also using the program as an opportunity to train indigenous rangers.

Loken explains: “We currently have a team of Wehea Dayak rangers who are independently monitoring camera traps in Wehea, downloading and analyzing data and writing reports. We have found that camera traps are a great way to engage local people and train them as parabiologists.”

Out of the thousands of photos snapped, Loken has been most surprised by the number of orangutans photographed on the ground, since these great apes are naturally arboreal animals.

“A few were genuinely interested in the camera trap, with one large male coming right up to the camera and looking at it,” he says.

Taking a series of some of the best photos from Wehea, Loken set it to music and posted it for supporters online. He notes, “To date, we have received more positive feedback on this video than any other video we have posted.”

The cryptic species

A giant armadillo in Brazil. Photo by: the Pantanal Giant Armadillo Project.

Let’s be honest, if you travel to the Amazon you’re more likely to see a jaguar (Panthera onca) or a lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris) than a giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus). In fact, you’re probably more likely to see a jaguar attack a tapir than a glimpse of the world’s biggest armadillo. One tour guide described the species to me as more mythical than real. So, how do you study something you may never see in person?

“Camera traps enable us to document and supply irrefutable evidence of the presence of secretive cryptic species in a way no other method can,” Arnaud Desbiez said. “By placing a camera in front of the burrow where I know a giant armadillo is sleeping I can get the exact time it goes out to forage and the exact time it comes back. I also get very close observation of the animal, which I simply cannot get [without the camera trap].”

Desbiez, with the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, is conducting a camera trap study of giant armadillos in Brazil’s great wetlands, the Pantanal. It’s the first camera trap study focusing specifically on this phantom animal.

“Due to its cryptic behavior and low population densities, the giant armadillo is one of the least studied species of the Dasypodidae family. The species is highly fossorial [i.e. spends time underground] as well as nocturnal and therefore rarely seen,” he says, adding, “almost nothing is known about them and most of the available information is anecdotal.”

Desbiez’s study is hoping to change this. Not only have his camera traps documented giant armadillos, but Desbiez also hopes the photos will prove fruitful in understanding giant armadillo behavior.

Camera trap photo of the Endangered Jentink’s Duiker (Cephalophus jentinki), Sapo National Park, Liberia © Ben Collen/ZSL/FFI/FDA. |

“Cameras can be set to trigger pictures in a rapid sequence. It is almost like having a movie. This can enable us to observe all kinds of behaviors. One of the objectives of this study is to document reproductive behavior of giant armadillos and we are counting on the camera traps,” Desbiez says, adding that “the best part of cameras is that they provide irrefutable evidence, which is easy to show and share with others.”

Desbiez and his team are even able to identify individual giant armadillos by light markings surrounding the individual’s armor. One thing that Desbiez has already discovered is that giant armadillo burrows play a bigger role in the ecosystem than anticipated.

“We really did not expect so many other species to be using the giant armadillo holes […] ranging from collared peccaries to tiny mice,” he says.

One day he hopes to photograph a baby giant armadillo.

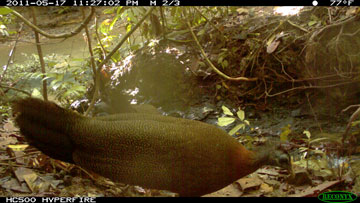

On the other side of the world, researchers are employing camera traps to document another incredibly elusive species, the pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis). One might think that given how easy it is to spot their giant cousins wallowing in a river bed, it would be relatively simple to find a pygmy hippo. But in addition to being much smaller, pygmy hippos occupy the dwindling thick rainforests of West Africa, not the plains of Sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, they are so cryptic that researchers only took the first photo of a wild pygmy hippo in Liberia in 2008.

Ben Collen, one of the expedition members, described seeing the first photo in a blog: “I think we all spoke at once. [One of our expedition members] whooped with joy, and then we had a round of applause. We excitedly flicked through the pictures to discover the hippo had returned.”

Collen is a research fellow at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and has worked with pygmy hippos through the EDGE program, an initiative of ZSL.

“Camera traps allow us to implement broader and more standardized monitoring networks across a wide range of species in a cost effective manner; gain new insight into the status and trends of species; and specifically link to one of the principal aims of our EDGE program: to implement conservation for Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered species,” Collen says.

While irrefutably proving that the pygmy hippo still survives in Liberia’s Sapo National Park was a major goal of the camera trap program, Collen says the number one aim was to “implement a long term wildlife monitoring program in [the park]. The camera trap survey was designed to detect wide ranging and cryptic species, and to detect change in occupancy over time.”

Camera traps give researchers around the clock access to places they could otherwise not get to and allow them to monitor species with very little disturbance to wildlife, Collen says.

.360.jpg) A Sunda clouded leopard (Nefelis diardi) can just barely be made out in the dark. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions. |

Camera traps have not only been employed to track shy insectivores (giant armadillos) and herbivores (pygmy hippos), but also long-unstudied carnivores. Recently camera traps set up in Gabon took the first publicly released video of the African golden cat, the least known feline on the continent. Unlike the other cats of Africa, the golden cat only inhabits rainforest, making it incredibly difficult to spot, let alone study.

“The African golden cat has dominated my thoughts and energy for over a year-and-a-half now,” University of Kwazulu Natal graduate student and Panthera Kaplan scholar Laila Bahaa-el-din recently said in an interview. “When carrying out a study like this one, you find yourself trying to think like your study animal. This helps put the camera traps in the right place.”

Bahaa-el-din managed to capture amazing footage of African golden cat sitting directly in front of the camera and another of the same individual chasing a butterfly. On watching the videos for the first time Bahaa-el-din says, “I felt, at last, like I was getting to know this elusive cat.”

Bahaa-el-din says her research is focused on understanding how the wild cat fares in logging areas.

“The video footage I recently captured was actually in a logging concession in central Gabon. It is recognized as having high standards of sustainable logging practices and has a zero tolerance for illegal hunting,” she explains. “At the particular area I had my cameras set up, logging had taken place just two years previously, and active logging was going on just a few kilometers away.”

The camera traps in the logging area also took photos of gorillas, elephants, aardvarks, leopards, and duikers, as well as a number of small mammals, says Bahaa-el-din.

“It indicated that logging alone should not mean the depletion of wildlife.”

Bahaa-el-din will next be comparing the abundance and diversity of mammals in the logging concession to pristine forest as well as a poorly-managed logging area. The evidence from the camera traps will eventually be used to develop a conservation plan for the African golden cat, which is getting its first taste of global publicity thanks to the remote cameras.

“Previous methods used for applying capture-recapture statistics involved physically trapping the animals, releasing them, and recapturing them. Not only would this be highly invasive to a species such as the golden cat, but it just wouldn’t be logistically possible due to the animal’s timid nature and difficult forest environment,” Bahaa-el-din says.

Camera traps for conservation

Setting up a camera trap, Sapo National Park, Liberia © Ben Collen/Zoological Society of London.

While many camera trap programs are established for the purpose of scientific research, conservation groups have also embraced the tool as a powerful way of reaching out to the public.

“Most species shown in our [camera trap videos] are hardly ever seen (alive) by human eye, our videos give the term ‘biodiversity hotspot’ a meaning which is understandable to everyone,” Marten Slothouwer says, adding that “the videos put Leuser on the map as one of the most important conservation area’s in the world.”

Slothouwer is running Eyes on Leuser, a video camera trap project in the Leuser ecosystem in Sumatra, which is being undertaken not for research, but for conservation publicity. [see several videos at the end of the article]

“Until now, almost no videos existed of most of Leuser’s cryptic wildlife,” Slothouwer continues, “our videos can make people realize that it’s worth it to save this forest, because it’s home to an incredible variety of species and there is no better way to show this than by video.”

To date the videos have proven successful in drawing an audience: an August 2011 compilation has been watched nearly 5,000 times on YouTube.com.

“It is nice when lots of people all over the world see that Leuser is an exceptional place,” Slothouwer says, but adds that it’s most important that Indonesians see them.

.360.jpg) The elusive marbled cat. Photo by Eyes on Leuser/Marten SLothouwer. |

“Only when local leaders and politicians take responsibility can something change.”

The decision to go with remote video cameras instead of the more commonly used photo cameras wasn’t difficult for Slothouwer.

“Videos have a strong power of expression, cost of distribution is low and it’s understandable to everyone. Videos leave a stronger and longer lasting impression then a written pamphlet, and people just love to see videos of animals that have never or rarely been filmed before,” Slothouwer says, adding, like Brent Loken, that he was impressed by “the numbers of viewers WWF attracts with video trap clips of rhinos and tigers.”

To date Slothouwer says he has been happily surprised at the number of species recorded. So far, he has captured footage of 27 species with just 10 camera video traps over a couple months. This includes incredible footage of a great argus pheasant (Argusianus argus) displaying for the camera; a bright-eyed banded civet (Hemigalus derbyanus) with tiger-like stripes sniffing the ground at night; a Malyan sambar (Rusa unicolor equina) flicking water and mud toward the viewer before settling in for a nice soak; an imposing Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) sniffing the video camera; the strange hedgehog-related moon rat (Echinosorex gymnura) rifling though the leaf litter; and a white-winged duck (Asarcornis scutulata) swimming with her chicks.

“I think the marbled cat (Pardofelis marmorata) in full color daylight is the most special video we got, and also the masked palm civet (Paguma larvata) is nice. It looks completely different compared to masked palm civets I’ve seen from other photo trap projects,” Slothouwer says.

As a filmmaker, Slothouwer prefers traditional wildlife documentaries to video camera traps, however this is the only way to catch many of these shy species on tape. In addition he says, “[videos from camera traps] really have something mysterious and exciting, you never know what will show up and what will happen.”

Slothouwer hopes the videos will make a long-term contribution to the protection of the Leuser ecosystem.

“The videos we collect can be used for several purposes, e.g. as a tool to reach a large international audience, to support conservationists lobby activities, for local education programs and to help to raise funding for conservation campaigns,” he says.

Sumatra can use all the conservation help it can get, as the island—Indonesia’s largest—has one of the highest deforestation levels in the world. According to a detailed report released by WWF, Sumatra has lost half of its forest cover since 1985. Approximately half a million hectares (larger than Rhode Island) of forest have been cleared annually, mostly for industrial palm oil and wood-paper plantations.

Nothing’s perfect

African golden cat in Lopé National Park, Gabon . Photo courtesy of Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

Of course camera traps are not perfect: like any tool they have their advantages and drawbacks.

Arnaud Desbiez, who is studying the giant armadillo, puts it this way: “Cameras are not limited in time…a proper camera, appropriately positioned (avoiding direct sunlight), can remain active in the field for over two months. Camera traps are discrete and do not scare animals so you can really get excellent pictures of animal behavior that would be difficult to observe. [But] camera traps are limited in space. They can only gather information in the tiny area where their sensors are positioned…Therefore animals can easily go undetected and you need a lot of cameras (which are expensive) to properly survey an area.”

A silverback gorilla sits in front of a camera trap. Photo by: Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera. |

The initial cost of camera traps is an issue, especially in developing countries, where camera traps are needed the most. According to Bent Loken, who is surveying the Wehea forest, a single camera trap ranges from $150 to $600, and that’s before one has to purchase other equipment such as extra batteries, battery chargers, and SD cards.

Camera traps also break. Tigers, elephants, and other big mammals have been known to attack camera traps, sometimes doing permanent damage. In addition, in areas where poachers are a problem, scientists often lose camera traps to people who understandably don’t like their photo being taken. Depending on the environment, humidity, rain, and extreme cold can be other issues.

In addition camera traps are only useful in cataloguing certain species, i.e. big to medium-sized mammals and birds mostly (though small rodents are often caught too). Bats may be photographed but are difficult to identify, since they are usually in flight. Small reptiles, amphibians, and, of course, insects rarely show up well enough to identify.

There are many things a camera trap can’t do; and in the end nothing beats sustained human observation of wildlife. There’s no way a camera trap could have achieved what Jane Goodall or Diane Fossey did.

The future of camera traps: Antarctica and beyond?

.568.jpg)

Bornean orangutan in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions.

This year, camera trapping hit a new milestone: it started snapping life on its seventh continent, Antarctica.

Ben Collen with ZSL explains: “My colleague Tom Hart and I are developing a number of projects looking at the impact of changing climate, expanding fisheries and other threats such as the impact of pollutants, on penguin populations.”

Collen says camera traps became a logical choice of tool after encountering a dearth in broad analysis of penguin populations.

“Therefore, we started to think about ways in which we could get around this and try to expand the currently quite limited monitoring network, and came up with camera traps as a possible solution,” he says.

Unidentified bird, possibly a great argus pheasant in Wehea Forest. Camera traps to date are also key in capturing photos of large and medium sized birds in the rainforest. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions. |

To get the broader view of penguin populations over time, Collen and Hart have set up camera traps overlooking penguin colonies. However, instead of taking a snapshot whenever a penguin walks by, the camera takes timelapse photos to document important events in a penguin’s season, “including timing of first arrival, first breeding, departure and chick fledging, as well as population numbers,” Collen explains, adding that, “consistent measurements of these types of data over time will hopefully tell us how penguins are adapting (or otherwise) to the different threats that they face; principally a changing climate.”

Bringing camera traps into Antarctica—one of the most extreme environments on Earth—forced Collen and Hart to develop some creative solutions to several problems.

“Batteries don’t function well and lose charge quickly at low temperatures, and we can have issues with equipment freezing. We’re trialing some different battery types which work well at lower temperatures, and insulating the equipment. Our ideal way of overcoming this would be to link up a solar panel—this could freeze over in the dark winter when nothing much is going on, and wake the camera up in time for breeding season, which is when we want the data,” Collen says, who adds that they’re still looking for just the right set-up.

But it’s not just the extreme cold that’s posing a problem.

“The other main issue we face is getting cameras overlooking penguin colonies to withstand the strong katabatic winds that are common in Antarctica. We’ve tried to solve this by placing the cameras on tripods, tied to matting, with several hundred kilos of rocks on top to weigh them down,” Collen says. “We’re also prodigious consumers of electrical tape to keep things secure.”

Even if they conquer the Antarctic, there are still many places camera traps haven’t been utilized.

So, why not aim high? A canopy camera trap could possibly document birds, reptiles, and monkeys in the rainforest canopy. Or low? Underwater cameras could document marine wildlife, in addition to the fauna of lakes and rivers. Perhaps with further technological advances, it may even be possible to use macro cameras to document the world’s micro-species. The future of camera trapping may only be limited by our imagination.

Camera traps are just one of the many new tools—including GPS, satellite monitoring of deforestation, genetic studies—used by researchers and conservationists in a rushed bid to catalogue life on Earth in an age of widespread environmental degradation. However, those setting up the traps hope the tool will do more than just leave photos of animals behind. They hope the camera trap will be one new armament in the battle to save the world’s species.

CITATION: Thomas E. Kucera and Reginald H. Barrett. A history of camera trapping. Pp. 9-26 in A. F. O’Connell, J. D. Nichols, and U. K. Karanth (eds.). Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses. Tokyo: Springer Inc. 2011.

The blue duiker (seen here with a calf). Photo courtesy of Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

.360.jpg)

A male Bornean orangutan on the ground in Wehea Forest. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions.

A giant pangolin caught on camera trap. Photo by: Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

A forest hog in Sapo National Park, Liberia. © Ben Collen/ZSL/FFI/FDA.

A chimpanzee checks out a camera trap. Photo by: Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

.568.jpg)

A muntjac in Wehea Forest. Photo by: Brent Loken/Ethical Expeditions.

_Laila.568.jpg)

Leopard mother with two cubs (barely visible in the back). Photo by: Laila Bahaa-el-din/Panthera.

Related articles

Forgotten species: the wild jungle cattle called banteng

(01/31/2012) The word “cattle,” for most of us, is the antithesis of exotic; it’s familiar like a family member one’s happy enough to ignore, but doesn’t really mind having around. Think for a moment of the names: cattle, cow, bovine…likely they make many of us think more of the animals’ byproducts than the creatures themselves—i.e. milk, butter, ice cream or steak—as if they were an automated food factory and not living beings. But if we expand our minds a bit further, “cattle” may bring up thoughts of cowboys, Texas, herds pounding the dust, or merely grazing dully in the pasture. But none of these titles, no matter how far we pursue them, conjure up images of steamy tropical rainforest or gravely imperiled species. A cow may be beautiful in its own domesticated sort-of-way, but there is nothing wild in it, nothing enchanting. However like most generalizations, this idea of cattle falls to pieces when one encounters, whether in literature or life, the banteng.

Feared extinct, obscure monkey rediscovered in Borneo

(01/20/2012) A significant population of the rarely seen, little-known Miller’s grizzled langurs (Presbytis hosei canicrus) has been discovered in Indonesian Borneo according to a new paper published in the American Journal of Primatology. Feared extinct by some and dubbed one of the world’s 25 most threatened primates in 2005 by Conservation International (CI), the langur surprised researchers by showing up on camera trap in a region of Borneo it was never supposed to be. The discovery provides new hope for the elusive monkey and expands its known range, but conservationists warn the species is not out of the woods yet.

Borneo’s most elusive feline photographed at unexpected elevation

(01/11/2012) Although known to science for 138 years, almost nothing is actually known about the bay cat (Pardofelis badia). This reddish-brown wild feline, endemic to the island of Borneo, has entirely eluded researchers and conservationists. The first photo of the cat wasn’t taken until 1998 and the first video was shot just two years ago, but basic information remains lacking. A new camera trap study, however, in the Kelabit Highlands of the Malaysian state of Sarawak has added to the little knowledge we have by photographing a bay cat at never before seen altitudes.

Camera traps snap 35 Javan rhinos, including calves

(01/04/2012) Camera traps have successfully taken photos of 35 Javan rhinos (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Ujung Kulon National Park. The small population, with an estimated 45 or so individuals, is the species’ last stand against extinction. Late last year, a subspecies of the Javan rhino, the Vietnamese rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus), was declared extinct.

Camera trap videos capture stunning wildlife in Thailand

.150.jpg)

(12/20/2011) A year’s worth of camera trap videos (see photos and video below) are proving that scaled-up anti-poaching efforts in Thailand’s Western Forest Complex are working. Capturing rare glimpses of endangered, elusive animals—from clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa) to banteng (Bos javanicus), a rarely seen wild cattle—the videos highlight the conservation importance of the Western Forest Complex, which includes 17 protected areas in Thailand and Myanmar.

Mysterious pygmy hippo filmed in Liberia

(12/19/2011) Conservationists have captured the first ever footage (see video below) of the elusive pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis) in Liberia. The forest-dwelling, nocturnal species—weighing only a quarter of the size of the well-known common hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius)—has proven incredibly difficult to study. But the use of camera traps in Liberia’s Sapo National Park has allowed researchers a glimpse into its cryptic life.

On the edge of extinction, giant ibis discovered in new region of Cambodia

(12/06/2011) The world’s largest ibis, and one of the world’s most endangered birds, has received some good news. A giant ibis (Thaumatibis giganteawas) has been photographed in the Kampong Som Valley in Koh Kong Province in Cambodia, the first record from this province in nearly a hundred years. Adults can grow to reach nearly 3.5 feet (106 centimeters) long.

Photos: biologists surprised by world’s biggest leopard in Afghanistan

(12/05/2011) When biologists with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) reviewed recent photos from camera traps in the Hindu Kush region of Afghanistan they were shocked to find a snarling image of the world’s largest leopard: the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor). Listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List, the subspecies was thought long-vanished from the Hindu Kush. Photos from the camera traps—automated cameras that use an infrared trigger to catch wildlife—also showed lynx (Lynx lynx), wild cat (Felis silvestris), Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), and stone marten (Martes foina).

Photos: camera traps reveal oil’s unexpected impact on Arctic birds

(10/26/2011) A study in the Alaskan Arctic, employing camera traps, has shown that oil drilling impacts migrating birds in an unexpected way. The study found that populations of opportunistic predators, which prey on bird eggs or fledglings, may increase in oil drilling areas, putting extra pressure on nesting birds. Predators like fox, ravens, and gulls take advantage of industry infrastructure for nests and dens, moving into areas that may otherwise be inhospitable. In addition, garbage provides sustenance for larger populations of the opportunists.

Illuminating Africa’s most obscure cat

.150.jpg)

(10/18/2011) Africa is known as the continent of big cats: cheetahs, leopards, and of course, the king of them all, lions. Even servals and caracals are relatively well-known by the public. Still, few people realize that Africa is home to a number of smaller wild cat species, such as the black-footed cat and the African wild cat. But the least known feline on the continent is actually a cryptic predator that inhabits the rainforest of the Congo and West Africa. “The African golden cat has dominated my thoughts and energy for over a year and a half now. When carrying out a study like this one, you find yourself trying to think like your study animal,” Laila Bahaa-el-din, University of Kwazulu Natal graduate student, told mongabay.com in a recent interview.