Everyone knows the tiger, the panda, the blue whale, but what about the other five to thirty million species estimated to inhabit our Earth? Many of these marvelous, stunning, and rare species have received little attention from the media, conservation groups, and the public. This series is an attempt to give these ‘forgotten species‘ some well-deserved attention.

Banteng bull caught on camera trap in Malua BioBank. Photo by: Sabah Wildlife Department (SWD).

The word “cattle,” for most of us, is the antithesis of exotic; it’s familiar like a family member one’s happy enough to ignore, but doesn’t really mind having around. Think for a moment of the names: cattle, cow, bovine…likely they make many of us think more of the animals’ byproducts than the creatures themselves—i.e. milk, butter, ice cream or steak—as if they were an automated food factory and not living beings. But if we expand our minds a bit further, “cattle” may bring up thoughts of cowboys, Texas, herds pounding the dust, or merely grazing dully in the pasture. But none of these titles, no matter how far we pursue them, conjure up images of steamy tropical rainforest or gravely imperiled species. A cow may be beautiful in its own domesticated sort-of-way, but there is nothing wild in it, nothing enchanting. However like most generalizations, this idea of cattle falls to pieces when one encounters, whether in literature or life, the banteng.

The banteng is everything domestic cattle are not: rainforest-dwelling, wild, elusive, obscure, almost mystical. Yet for all that, the banteng are cattle. They just happen to be cattle of the tropical forests of Southeast Asia, sharing their dark verdured habitat with tigers, elephants, and rhinos. Although co-existing with such exotic animals, the banteng, in appearance, could almost be mistaken for domestic cattle; they are similar in both size and general impression, but a bit different in color and pattering: males sport a black coat with white stockings and rump, while females are tan to dark brown with similar stockings and rump.

Footprints of the rarely sighted banteng in Tabin Wildlife Reserve. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

“Banteng are one of the few remaining species of totally wild bovids in the world,” Penny Gardner, who is studying banteng in Borneo, says. “The behavior of the banteng is unique because they spend the majority of their time in dense remote forest, emerging at night and early morning to forage on grasses growing at the edge of the forest or in glades. They are incredibly elusive and rarely sighted.”

A PhD student at Cardiff University, Penny Gardner is currently tracking banteng in two protected areas—Tabin Wildlife Reserve and Malua BioBank—in the Malaysian state of Sabah through the Danau Girang Field Center and Sabah Wildlife Department. Although wild banteng are found in several countries, including Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, Borneo’s banteng are considered by many to be a distinct subspecies.

“They are the last large mammal of Borneo to be researched and very few people worldwide have heard of them. The threat of extinction is imminent; they are extinct from Brunei and Sarawak (Malaysia Borneo), and only occasional sightings of tracks are reported in Kalimantan (Indonesia Borneo). Sabah is the last stronghold, however the remaining forest habitat is fragmented and populations are isolated,” she says. While the banteng is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List, Gardner says that listing comes from a “crude population estimate conducted in the 1980s.” Today, the species may be on the verge of disappearing.

“In reality, [the banteng] is the second most endangered large mammal in Borneo, after the Sumatran Rhino,” explains Gardner. The species, across its range, is being pummeled by deforestation and poaching. Forests across Southeast Asia are being converted into palm oil, rubber, paper and pulp plantations at record rates. Although a protected species in all of its range states, the banteng is still illegally hunted with law enforcement lacking due to a dearth of funds. Given low populations and fragmentation of habitat, Gardner says the banteng is also facing “a reduction of gene flow between populations, (probable) inbreeding, hybridization with domestic cattle and disease transmission with domestic livestock.” With the number of threats extinction may appear inevitable, but the situation is not yet hopeless.

Employing camera traps, Gardner has secured photos of a healthy herd in Malua BioBank, which was granted protection in 2008 largely due to its substantial population of orangutans. Given the banteng’s well-known elusive personality, Gardner has depended heavily on camera traps to document the species. Camera traps, which take photos remotely of wildlife when an animal “trips” an infrared sensor, have become incredibly important to recent studies of rare tropical animals. Researchers are able to sift an incredible amount of information from photos.

The Bornean Banteng Program team in Malua BioBank. Photo by: Penny Gardner. |

“We use camera traps for confirming the presence of banteng, recording the times, dates and duration of their presence, identifying the number of individuals in a herd, and for monitoring breeding activity. The photographs also provide an indication of overall body condition, as well as capture unique scars and markings which allow us to recognize individuals. We create ID profiles for recognizable banteng and are able to monitor their growth, body condition, movement and herd association,” explains Gardner adding that, “Collaborations with researchers studying other mammals using camera traps has provided additional photographs of banteng and, in some instances, I have been able to recognize banteng from photographs dating back years!”

The photos are becoming the foundation for the first-ever study of the Bornean banteng, including population, behavior, breeding, health, and range. Gardner and her team also examine tracks and dung. Meanwhile, a new and extremely ambitious part of the project is upcoming.

“This year we aim to fit GPS-Satellite tracking devices to some individuals so we can estimate home range size, dispersal distances and use of the forest habitat; this will require thorough planning and preparation and, if successful, it will be a huge accomplishment and the turning point in our understanding of banteng’s behavior in the surrounding environment landscape,” says Gardner.

Once the masses of data is gathered and analyzed then comes the next step: conservation. The information from Gardner’s work will eventually be used to come up with an action plan as to how best conserve the banteng in Sabah. Hopefully, the data will aid other banteng-range countries in developing additional plan to save the rainforest cattle.

“In the meantime,” says Gardner, “we need to ensure the perpetuity of all banteng herds, and other endangered fauna, by conserving and protecting their habitat, and by creating wildlife corridors between isolated forests. Additional steps include stemming the supply of illegal banteng meat by identifying hunting locations and supply chains, and tightening the penalties for those caught conducting this illegal activity, and increasing the awareness of this species through education and media both locally and globally.”

Although Gardner is focusing on the Bornean banteng, little more is known about the other subspecies on the Asian mainland and Indonesian islands. No one knows how many banteng survive in total, but it’s likely not more than a few thousand. A few hundred banteng are thought to still survive in Cambodia’s Mondulkiri Province; the Indonesian island of Java has four or five populations of over fifty animals each; populations in Thailand and Laos are likely very small; and no one knows about Myanmar. Almost all of these populations are declining due to similar problems: poaching and habitat loss.

In a bizarre twist, the largest wild banteng population in the world is in Australia. Some 6,000 animals roam today on Australia’s Cobourg Peninsula, all descended from around 20 individuals abandoned there in the late 19th Century. Technically an invasive species, Australia has had to ponder how to deal with the large endangered mammal. To date they have largely let it be given that the fish-out-of-water population is a possible safeguard against complete extinction: if little is done in Asia, Australia may be the banteng’s last refuge.

Despite the animal’s scarcity and legendary shyness, Gardner has been fortunate enough during her long days of field work to run into the species—once. She says that her team was “incredibly lucky” to see a herd during July of last year, noting that “there are some people who have worked in the forest for decades and have never ever seen a banteng.”

Photo from Gardner’s chance encounter with banteng herd. Photo by: Penny Gardner. |

“We were walking along the edge of the forest searching for Banteng tracks when we spotted the herd of approximately 15, which included young calves, juveniles, cows and one large bull,” she says. “We were keen to take a closer look to see if we could identify any of the herd from the profile catalogue I’ve created […] We approached the herd cautiously as we did not want to startle or disturb them so we kept partially hidden by the roadside shrubbery. We were positioned downwind from the herd so they could not pick up our scent however they still noticed us but […] to my surprise they did not appear to be alarmed. The banteng were actually very curious about our presence and slowly moved towards us, stopping every few steps. Unfortunately the wind direction changed and they quickly picked up our scent and headed back into the forest. As they trotted back into the forest, we had a spectacular view of their characteristic white rump and stockings.”

The sighting actually convinced one of her field assistants that the banteng was in fact real and not a myth. Unlike orangutans, elephants, clouded leopards, and even Sumatran rhinos, the banteng is almost wholly unknown to the public.

“I would say the vast majority of people within Sabah do not know about the banteng. Those people that have heard of them are either involved in wildlife research or protection, nature related tourism, or live near to the forest,” says Gardner, adding that knowledge is likely even less abroad. “Globally speaking, the Banteng is probably only known to wild cattle specialists […] Of the people I have spoken to, many have difficultly in believing there are wild cows (Bovidae) in the tropical jungles of Borneo and others are resolute the Banteng are not wild at all but are in fact feral cattle.”

But wild cattle species like the banteng, living their lives hidden among the dense, but vanishing, forests of Asia, are actually surprisingly numerous. On the Indonesian island of Sulawesi dwell two tiny wild cattle called anoas (lowland anoa: Bubalus depressicornis, and the mountain anoa: Bubalus quarlesi); likewise on the Philippine island of Mindoro roams a small, and Critically Endangered, buffalo-like animal known as the tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis). Wild water buffalos (Bubalus arnee) still survive in India and wild yaks (Bos mutus) in Tibet. The large bovine, the gaur (Bos gaurus), makes its home across much of Central and Southeast Asia and is probably the least endangered of Asia’s wild cattle species. The kouprey (Bos sauveli) was once found in a small region of Southeast Asia, but may now be extinct: an individual hasn’t been seen since the 1980s. But not all wild cattle news is depressing: in 1992, scientists made the remarkable discovery of a new large mammal: the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in Vietnam. Although it looks like an antelope, the incredibly cryptic animal is actually most closely related to bovines.

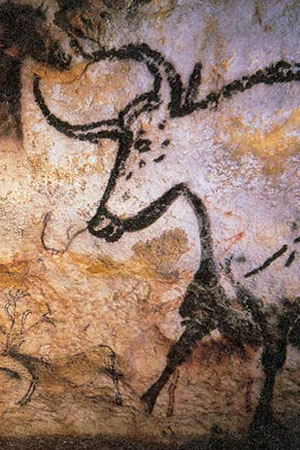

Auroch painted on the cave walls of Lascaux. Photo by: Prof Saxx. |

With so many beloved, and endangered, species in Southeast Asia—tigers, elephants, orangutans, rhinos—the banteng, and many of its relatives, have been largely overlooked. But Gardner says there is definitely still time to save these wild cattle. She says people can help by supporting conservation projects working with banteng and signing petitions against deforestation in the region. In addition, Gardner says: “put up a poster at your workplace in support of a scientific research project, and talk about the species to anyone and everyone. […] Refuse to buy timber products such as hardwood laminate floors which are sold as uncertified or untraceable. If you go abroad don’t buy souvenirs made from animal parts, or products likely to have come from the jungle. Take your rubbish out of the forest and insist your hotel or lodge recycle their waste. Lastly, if you’re part of the social mania, add news feeds about banteng (Borneo Banteng Program) to your FaceBook page, twitter account or own webpage.”

In 1627, the last auroch (Bos primigenius) died in the forests of Poland. Once widespread throughout Europe, North Africa, and Asia, the auroch is the ancestors of today’s familiar domesticated cattle. Aurochs, however, like banteng were wild; they were bigger, denser, and fiercer than today’s domesticated version like comparing Superman with duller Clark Kent. They had to take on predators from wolves to leopard to lions. They even fought gladiators in the Roman games. These uber-cattle grace some of the world’s earliest cave paintings and were worshiped by some ancient cultures. But the auroch eventually met its end due to many of the same forces that today imperil the banteng: habitat loss, over-hunting, and breeding with domestic cattle. While the auroch is long gone (though some researchers hope to re-create the species through genetic research) the banteng is not. There is still time to save this wild, rainforest bovine; this cryptic, orange-colored cow; this animal who has the capacity to change our minds about the mundaneness of cattle.

The Borneo Banteng Program would like acknowledge its sponsors and collaborators: Sabah Wildlife Department (Dr. L. Ambu), Danau Girang Field Centre (Dr. B. Goossens), and the NGO HUTAN (Dr. M Ancrenaz), with funding from Houston Zoo, the Malaysian Palm Oil Council, the Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and Woodland Park Zoo. The project collaborates with several partners such as the Sabah Forestry Department, New Forests Asia Sdn Bhd and the Malua Biobank Project, Cardiff University, and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research whom kindly provided all camera traps.

Female banteng in Alas Purwo National Park, Java, Indonesia. Photo by: Rochmad Setyadi.

Female Bornean banteng caught on camera trap in Malua Forest Reserve. Photo by: Sabah Wildlife Department (SWD).

A camera trap photo catching a dominant bull and two bullocks simultaneously feeding from the artificial salt lick in Malua Forest Reserve. Photo by: Sabah Wildlife Department (SWD).

Camera trap photo: a large herd with young calves visiting the artificial salt lick in Malua Forest Reserve. Photo by: Sabah Wildlife Department (SWD).

Gardner teaching field assistant to collect banteng dung samples. Photo by: Penny Gardner.

On the road to Tabin Wildlife Reserve through 26 kilometers of oil palm plantations. Tabin is in the far distance. Photo by: Penny Gardner.

The oil palm plantations surrounding the west of Tabin Wildlife Reserve. Photo by: Penny Gardner.

To discover more of the world’s forgotten species: Click Here.

Related articles

Group releases photos of Borneo rainforest to be converted for palm plantations

(01/27/2012) The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) has released a set of photos from a visit to a contested area of forest set to be converted for oil palm plantations in Indonesian Borneo.

Feared extinct, obscure monkey rediscovered in Borneo

(01/20/2012) A significant population of the rarely seen, little-known Miller’s grizzled langurs (Presbytis hosei canicrus) has been discovered in Indonesian Borneo according to a new paper published in the American Journal of Primatology. Feared extinct by some and dubbed one of the world’s 25 most threatened primates in 2005 by Conservation International (CI), the langur surprised researchers by showing up on camera trap in a region of Borneo it was never supposed to be. The discovery provides new hope for the elusive monkey and expands its known range, but conservationists warn the species is not out of the woods yet.

Indonesia to set aside 45% of Kalimantan for conservation

(01/19/2012) Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) on Thursday announced a regulation that would protect 45 percent of Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo, according to a statement issued by his office.

Borneo’s most elusive feline photographed at unexpected elevation

(01/11/2012) Although known to science for 138 years, almost nothing is actually known about the bay cat (Pardofelis badia). This reddish-brown wild feline, endemic to the island of Borneo, has entirely eluded researchers and conservationists. The first photo of the cat wasn’t taken until 1998 and the first video was shot just two years ago, but basic information remains lacking. A new camera trap study, however, in the Kelabit Highlands of the Malaysian state of Sarawak has added to the little knowledge we have by photographing a bay cat at never before seen altitudes.

Wildlife official: palm oil plantations behind decline in proboscis monkeys

(12/05/2011) The practice of palm oil plantations planting along rivers is leading to a decline in proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus) in the Malaysian state of Sabah on Borneo, says the director of the Sabah Wildlife Department, Laurentius Ambu. Proboscis monkeys, known for their bulbous noses and remarkable agility, depend on riverine forests and mangroves for survival, but habitat destruction has pushed the species to be classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List.

Small mammals use Borneo pitcher plant as toilet in exchange for nectar

(11/08/2011) Tree shrews and nocturnal rats in the forests of Borneo have a unique relationship with carnivorous pitcher plants. The mammals defecate, and the pitchers are happy to receive. A study published on May 31 in the Journal of Tropical Ecology shows a species of giant mountain pitcher plants (Nepenthes rajah) supplements its diet with nitrogen from the feces of tree shrews (Tupaia montana) that forage in daylight and summit rats (Rattus baluensis) active at night. When the small mammals lick nectar from the underside of the pitcher’s lid, they stand directly over the jug-shaped pitcher organ.

Malaysia must take action to avoid extinction of its last rhinos

(11/05/2011) Malaysia must take immediate action to prevent the extinction of the handful of rhinos that survive on the island of Borneo, says a coalition of environmental groups.