Aerial view over Latvian forests—please note almost all cutting patches are fresh, not yet regenerated. Photo by: R.Matrozis, 2007.

The economic crisis has pushed many nations to scramble for revenue and jobs in tight times, and the small Eastern European nation of Latvia is no different. Facing tough circumstances, the country turned to its most important and abundant natural resource: forests. The Latvian government accepted a new plan for the nation’s forests, which has resulted in logging at rates many scientists say are clearly unsustainable. In addition, researchers contend that the on-the-ground practices of state-owned timber giant, Latvijas Valsts meži (LVM), are hurting wildlife and destroying rare ecosystems.

The issue hit a head in 2010 when the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) abandoned LVM due to concerns with some of its practices. However, LVM is now pursuing re-establishing its FSC credentials, which certifies forests around the world as sustainably managed. To date, the FSC has re-certified four of LVM’s forest management districts according to the company. Yet deep concerns linger among local scientists about the sustainability of logging and the damage to ecosystems and wildlife in Latvia—and for many environmentalists the FSC is no guarantee of changed practices. The organization has faced harsh criticism for certifying companies that practice clearcutting, logging in old-growth forests, and establishing monoculture plantations.

Even as LVM regains bit-by-bit certification by the FSC, concerned researchers warn that Latvia is in danger of its losing protected species and habitats, as well as its precious natural heritage, in a single generation.

Forests: Latvia’s heritage

The hermit beetle (Osmoderma eremita) considered the most “protected” species of insects as it’s covered by several international and national law acts. This species is closely connected with old, hollow trees where its larvae develop. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2006.

Lying at the intersection of western Russia, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe, Latvia’s great forests represent as much a collision of diverse wildlife communities as its geographical placement is a collision of European cultures.

“The unique situation of Latvia is in being the crossroads for several faunas, like Euro-Siberian, Mediterranean-Central European, and North European,” explains Dmitry Telnov with the Entomological Society of Latvia. “This combination is a key to understanding the high species diversity in Latvia.”

Although a small country, Latvia’s rich forests provide homes to a remarkable abundance of wildlife. The nation has the highest population densities of lynx (Lynx lynx) and beaver (Castor fiber) in the European Union, and not long ago the highest density of black storks (Ciconia nigra). The country is also home to wild boar (Sus scrofa), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), white-backed woodpecker (Dendrocopos leucotos), and moose (Alces alces), and a few resident bears (Ursus arctos). In fact, unlike much of Europe, Latvia still retains self-sustaining populations of historic top predators, including between 500-1,000 Eurasian wolves (Canis lupus lupus). The Baltic nation is also home to about 20 percent of the world’s population of lesser spotted eagles (Aquila pomarina), just one of 344 bird species documented in the country. In addition, its forests and wetlands also harbor over 100 species of molluscs as well as many rare and vanishing plants.

The western capercaillie, male in flight. Photo by M. Strazds, 2010. |

Besides providing habitat for some of Europe’s most stunning and rare wildlife, Latvian forests protect the headwaters of the nation’s rivers, prevent erosion, sequester carbon, and provide food, income, and fuel for rural Latvians.

“Forests are also very important for country-side people as a source of berries and mushrooms […] and in villages where [unemployment is high] it is an important source of income,” says Sandra Ikauniece, a Latvian ecologist.

In fact, the boreal pine forest is not only the dominant ecosystem of Latvia, but has also imprinted itself in the Latvian way-of-life.

“It is Latvia’s landscape, having a very solid footprint in our language: the word ‘forest’ is used mostly in singular wile all other landscape types—like fields, meadows, etc. are in plural—reflecting the past reality of one big forest […] and such as essential part of Latvia’s cultural and natural heritage,” explains Dr. Māris Strazds, with the Latvian Ornithological Society.

Unfortunately, only about 0.4 percent of Latvia’s forests are today considered primary, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Still, many of the forests are old and biodiverse. As Ikauniece says, compared to other forests in Europe, Latvia’s are “untouched.” Currently the FAO estimates that just over 50 percent of Latvia is under forest cover, a remarkable number compared to many other EU nations. However, even this statistic is misleading: as an area can still be considered forested if it was only recently clearcut and has only been replanted with tiny saplings, resembling more an urban garden than a forest. Around 15 percent of Latvia’s forest are re-planted saplings rather than true forest. In the end, no one in Latvia is saying publicly just how much standing, intact forest is left and how much has been lost.

Fuzzy math

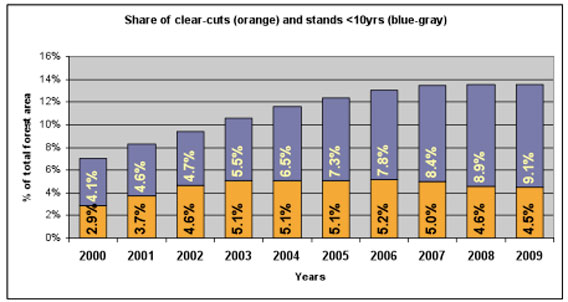

Estimated percentage of Latvian forest that is comprised of clearcuts and young stands (less than 10 years old).

Following the economic crisis, Latvia sacrificed its forests through dubious math. According to Dmitry Telnov, the government, represented by the Ministry of Agriculture, and industry recalculated forest regeneration rates quite optimistically and then compared this to a recent decline in private (non-LVM) harvesting.

Currently, just over half of Latvia’s forest land are under state, i.e. LVM, control while the rest is owned by private companies and individuals. On paper the ensuing calculation suddenly allowed LVM to chop 2 million cubic meters additionally every year. Argued as “sustainable,” the new harvesting rates were pushed through the Latvian government without scientific input [LVM did not respond to repeated queries related to this article].

But Dr. Māris Strazds told mongabay.com that the changes in forestry has resulted in a situation that is clearly unsustainable in the long-term with an ultimate collapse of the industry if changes aren’t made.

Latvian timber for customers overseas. Photo by: R. Matrozis, 2009. |

“Current practices can be continued circa 50 years (with nothing being left by then) while the average rotation period of all tree species present (considering share and cutting age of each species) is around 71 year. There is no other way of keeping any forestry ongoing than by changing legislation—either by reducing or removing cutting age as a operational threshold at all.”

Part of the problem stems from the close connection between LVM and local scientists. According to Telnov, the forest research institute “Silava” is to a large extent dependent on LVM for grants, implying that researchers must go along with the company’s mantra or risk a loss of funds. This has endangered the forestry sector not just in the future but today. Strazds goes on to say that given the realities of Latvian forestry, “There are many indications of a shortage in logging volumes already.”

Even as the Latvian economy picked up some steam in 2010, cutting rates were not changed. During the same year LVM lost its Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. Interestingly at the time LVM released a press statement stating it “supported” its termination from the FSC. The company argued that “the transparency of certification procedures and quality of the auditing process” was deeply flawed while the cost of certification was not worth it. Despite these statements, LVM has been pushing for FSC re-certification ever since.

Roberts Strīpnieks, chairman of the board at LVM, said in statement that “the new FSC certificates are good news to our cooperation partners, as they allow [us] to increase the supply volumes of timber certified this way.”

In the end, economic woes “served as an excuse to increase the total amount of harvesting state forests (most important part of forests in terms of biodiversity conservation) without any safeguards for biodiversity while at the same time weakening the system of nature conservation and State Forest Service (the authority following the implementation of laws and regulations, including nature protection, in forests),” explains Viesturs Kerus with the Latvian Ornithological Society.

Ecosystems and wildlife

Over 55,000 pairs of beaver are found in Latvia. Photo by: V.Skuja.

It’s not just the massive scale of logging that has scientists concerned, it’s also the forestry practices themselves. In fact, according to Sandra Ikauniece, LVM lost its FSC certification not because of sustainability problems, but due to the company not identifying protected ecosystems before cutting—in some cases destroying habitats meant to be protected under European law [the FSC also did not respond to repeated queries on the story].

Aside from simply not identifying protected ecosystems, and thereby clearcutting everything in a particular area, the company also found ways to cut such forests legally by claiming sanitation cuts to control insects or disease.

“If a ‘pest invasion’ is ‘registered’, it is interpreted as a threat to state forests (both inside and outside the protected areas) and such areas can be logged out,” explains Telnov.

Moist forests or wetlands (this is a black alder mixed forest) are rich in dead wood and very important habitats for internationally protected animals like black stork, crane and beaver. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2007. |

According to its website, LVM, which controls half of Latvia’s forests, must manage “at least 20 percent of [its] forest […] with the goal of preserving and expanding biological diversity and at protecting the environment. Elsewhere the main goal is to extract as much valuable timber as is possible.”

However, researchers say in reality only about 4 percent of Latvia’s forests are under strict protection—i.e. no cutting allowed. But differing definitions of “protection” has created confusion.

“[There is a] permanent discrepancy among various interest groups [regarding] how much protected forests we have—from just a few percent (around 4 percent) if only strictly protected forests are considered where no forestry measures are allowed […] up to ‘about one half’ of all forests considering any restriction,” explains Māris Strazds.

One of the key habitats of concern is wetland forest. Dmitry Telnov told mongabay.com that he had evidence of the “loss of several patches of old-growth aspen wetlands.” He adds that “[that] these areas [were] inhabited by several internationally and locally protected (also EU level) species of insects and plants. These species are well-known also by the ‘environment experts’ of LVM, but have been ignored when planning their deforestation.”

LVM is also imperiling forest wetlands through re-establishing decades-old drainage systems and building new roads, says Māris Strazds. However, none of the researchers know just how much wetland forest has been impacted in recent years, as that information has not been provided publicly.

The black stork is one of Latvia’s key protected species in forest habitats. Photo by M. Strazds, 2010. |

“Several research projects proposed on this subject have been blocked by lobby from the Ministry of Agriculture,” says Strazds.

Even National Parks are not immune to commercial logging. National Parks in Latvia “are forced to cut some of their forests in order to ‘complete’ their budgets,” says Māris Strazds.

On the books Latvia has a number of progressive laws protecting particular species, some of which also fall under EU laws, but many of these species are unprotected in reality because no one knows where they are.

“Distribution of protected species of flora and fauna in Latvia is incompletely known: in Soviet times it wasn’t priority, nowadays there isn’t enough funding for this kind of research. So LVM only avoids cutting around known populations of protected species, especially true for invertebrates” explains Telnov.

Bird nests, especially for lesser spotted eagles and black storks, have also become a contentious issue. These nests are meant to remain undisturbed, but Strazds says there is “little doubt” that some foresters quickly remove the nests and go ahead with clear-cutting.

Viesturs Kerus adds that “indirect evidence shows that most of the nests that are known to the staff of LVM are never revealed to nature conservation institutions.”

In addition, the ornithologists say birds are disturbed during sensitive breeding times, a situation that may be causing declines in some species.

“Cutting forests in spring not only destroys tens of thousands of bird nests every year but also causes significant disturbance for several forest birds and [is] responsible for the abandonment of a significant portion of black stork nests,” says Kerus. Spring disturbance has been cited as one of the major reasons behind the loss of black storks.

A European elk (or moose as its known in North America). Elk are still abundant in Latvian forests, including these very close to the Latvian capital of Riga. Photo by: R. Matrozis, 2011. |

Finally, there is the fact that LVM doesn’t practice selective logging, but clearcutting. As its name suggest, clearcutting simply means felling every tree in a specific area leaving only a few so-called “ecological” trees standing per hectare. Not only does this destroy the targeted area, but it also opens up adjacent forest lands to “edge effects” which includes battering by winds, as well as non-optimal conditions of light, temperature and humidity. These unsheltered and fragmented forests become particularly vulnerable to degradation with negative effects spreading far past the cut line.

“So ‘old’ stands adjacent to clearcuts cannot be considered forest interior anymore,” explains Strazds. Fragmenting forests also changes the populations of animals.

“Habitat fragmentation is a ‘new chance’ for one group of species and a natural disaster for other species. For typical forest species (lynx, black stork) clearcuts are like ‘wounds’ on the body of their natural habitat,” says Telnov. “Natural regeneration of the forest habitat to the old-growth condition takes more than 80 years in Latvia (depending on the type of the habitat), so longer than one average human generation.”

Clearcuts may even impact predator presence. Forest species like lynx may be replaced by the more adaptable crows and fox, which could hurt some bird populations, such as the majestic capercaillie.

The road ahead

It may not be long till the great forests of Latvia start to look like those of Western Europe: fragmented and fractured. Some forest species—like the lynx, the bear, the capercaillie, the moose, beaver, black storks, and the wolf—could vanish for good, while others may hang-on in a pathetic state. In which case Latvia would have lost not only its splendid wildlife and ecosystems, but also its deep historical and cultural identity.

“Boreal forests are not less important both for nature conservation and climate stabilization than tropical rainforests. Society should remember and realize this fact,” Telnov says.

Telnov says he expected changes to occur, or at least more media coverage, when Latvia lost its FSC rating, however, he says, “almost not a single company in Western Europe or the U.S, stopped purchasing Latvian timber or timber products (for example, Britain, Germany, France and other continued to be customers of LVM and their subcontractors). It was a shock for me. Everybody in the West is aware of tropical forest destruction, but almost nobody within the EU reacted against LVM.”

The abundance of dead wood in Latvia’s forests is partly enforced by masses of snow during long the Latvian winter, when weaker trees topple from the snow’s weight. This dead wood is usually of small dimension and mostly useful for invertebrates only. Photo by: D.Telnov, 2010. |

Many fingers point to ambivalence in Britain, where over a third of Latvian timber ends up.

The scientists agree that one of the first changes needed in Latvia is funding for independent research—with no ties to LVM or the Latvian government. Currently, says Strazds, “alternative research or complaints against forest industry often results in a funding ban (in real terms) for those researchers involved in such projects.” According to Strazds and the others international donors need to support local researchers working to answer questions such as what sustainable forestry in Latvia would look like or where and how are species really faring in Latvia’s boreal? In addition it wouldn’t hurt if more people far-and-wide were aware of what was occurring in the country.

“International support (at least—interest by large mass media or groups of scientists) is needed in order to raise the problem to international level. We need to be seen from outside our state borders!” Telnov says.

Next, forestry laws need to change, but this time conservationists and scientists need to be allowed to participate in the legislative process.

The Latvian public—which Telnov says is bombarded by a “massive” LVM campaign—could also use more education and information on the issue. Kerus says people outside Latvia must make sure the wood they are purchasing is “really sustainably harvested” and should also consider visiting Latvia to enjoy its unique forests and prove to the government “there are other (economic) values to the forests, not only timber production.”

However, Ikauniece adds that it may take a new generation of leadership to make a true turnabout on the issue. If so the question then becomes: how much forest will be left by then?

For these scientists the question isn’t ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to any logging, but how much logging is too much? In addition, what practices should be followed, and enforced, to make certain the forests Latvians currently enjoy and rely on will still stand tall for their children, and their children’s children?

“Latvian forests are crucial for the economy of the country and should be maintained in an interest of the whole nation and not of single state company owing most of the forested land,” Telnov says.

A lynx in Latvia. Photo by: V. Skuja.

Marchantia sp. mosses are not uncommon in various types of forested and non-forested habitats over the country. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2007.

The European peacock (Inachis io) is very abundant in Latvia. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2008.

The slow worm (Anguis fragilis) is typical species for dry Scots pine forests but often killed by road traffic. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2008.

The Bulin snail (Ena montana) only occurs in old-growth deciduous to mixed forests with a high amount of decaying wood and high soil humidity. Photo by: D. Telnov, 2006.

Despite urbanization, about 1/3 of Latvian population lives in the countryside. Traditionally, forests provided Latvians with building material and most of the houses are built from wood. Photo by: R.Matrozis, 2010.

Related articles

Is the Russian Forest Code a warning for Brazil?

(12/19/2011) Brazil, which last week moved to reform its Forest Code, may find lessons in Russia’s revision of its forest law in 2007, say a pair of Russian scientists. The Brazilian Senate last week passed a bill that would relax some of forest provisions imposed on landowners. Environmentalists blasted the move, arguing that the new Forest Code — provided it is not vetoed by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff next year — could undermine the country’s progress in reducing deforestation.

Global forest cover lower than previously estimated, says UN

(11/30/2011) Global forest cover, as well as forest loss, is lower than previously estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), according to a new satellite-based assessment that replaces the self-reporting system previously used by the U.N. agency.

Deforestation could be stopped by 2020

(11/28/2011) If governments commit to an international program to save forests known as REDD+, deforestation could be nearly zero in less than a decade, argues the Living Forests Report from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). REDD+, which stands for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, is a program that would pay developing nations to preserve forests for their ability to sequester carbon. Government officials begin meeting tomorrow in Durban, South Africa for the 17th UN climate summit, and REDD+ will be among many topics discussed.