How does one estimate the number of tiny, cryptic “galling” insects without finding and describing every one (a task that could take centuries of taxonomic work)? According to a new paper in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science, you count the plants. Galling insects use plant tissue for development creating a “gall,” or abnormal growth on the plant. Such little-known insects include gall wasps, gall midges, aphids, and jumping plant lice. The groups are known to be highly diverse, with over 2,000 species described from the US alone; scientists have previously estimated that there may be as many as 132,000 different species.

“[Galling insects] are capable of manipulating plant tissues to form complex structures that are efficient both for nutrition and for defense against the natural enemies of these insects. All of these characteristics make this group one of the most diverse guilds of herbivorous insects,” writes the paper’s author, Walter Santos de Araújo.

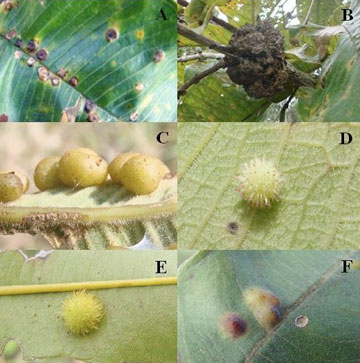

Insect galls on plants in Brazil’s cerrado. Photo by: © Walter Santos de Araújo. |

By counting unique insect galls on plant species in 15 sites in Brazil’s cerrado, Araújo makes the case that one can use plant species as a surrogate for total galling insect diversity, since these tiny insects depend on plants for survival. The researchers counted 112 galling insect species on 64 different plants.

“Our results show that the local richness of [galling insects] is positively influenced by host plant richness, suggesting that this is a good predictor of galling insect diversity,” Araújo writes. “Most galling species have a species-specific relationship with their host, supporting the hypothesis of a relationship with plant richness.”

The paper concludes that plant diversity provides a “good tool” for determining the overall richness of galling insects.

CITATION: Santos de Araújo, W. 2011. Can host plant richness be used as a surrogate for galling insect diversity? Tropical Conservation Science. Vol. 4(4):420-427.

Related articles

Monarch butterflies decline at wintering grounds in Mexico, Texas drought adds to stress to migration

(11/10/2011) Every fall, millions of monarch butterflies travel south to Mexico and take refuge in twelve mountain sanctuaries of oyamel fir forests. Now, declining numbers of the overwintering butterflies expose the migration’s vulnerability and raise questions about threats throughout the monarch’s lifecycle. A study published online last spring in Insect Conservation and Diversity shows a decrease in Mexico’s overwintering monarch butterflies between 1994 and 2011. The butterflies face loss of wintering habitat in Mexico and breeding habitat in the United States. Extreme weather, like winter storms in Mexico and the ongoing drought in Texas, adds yet another challenge.

Beetle bonanza: 84 new species prove richness of Indo-Australian islands

(11/08/2011) Re-examining beetle specimens from 19 museums has led to the discovery of 84 new beetle species in the Macratria genus. The new species span the islands of Indonesia, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, tripling the number of known Macratria beetles in the region. “Species of the genus Macratria are cosmopolitan, with the highest species diversity in the tropical rainforests. Only 28 species of this genus were previously known from the territory of the Indo-Australian transition,” Dr. Dmitry Telnov with the Entomological Society of Latvia, who discovered the new species, told mongabay.com.

Meet the just discovered ‘Komodo dragon’ of wasps

(08/28/2011) A new species of warrior wasp has been discovered on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi that is so large and, frankly, terrifying-looking that it has been dubbed the ‘Komodo dragon’ of the wasp family. Bizarrely, the male of the species has jaws that outstretch its limbs. “I don’t know how it can walk,” said the wasp’s discoverer, entomologist Lynn Kimsey of the University of California, Davis and director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology, in a press release. “Its jaws are so large that they wrap up either side of the head when closed.”