Hawaii evokes images of a tropical paradise where fragrant flowers, vivid colors, exotic plants, birds, and

fish abound. Unfortunately, much of Hawaii’s original native flora and fauna has disappeared since the

arrival of Europeans in the 18th Century. Hawaii now has the dubious distinction as having become the

planet’s extinction capital, having lost more than 55 endemic species (mostly native forest birds) which

account for nearly one third of recorded of bird extinctions since the 1700s.

The following is an interview with Alan Lieberman and Richard Switzer of the San Diego Zoo Institute for

Conservation Research’s Hawaii Endangered Bird Conservation Program. Along with a multi-institutional

team, their group is racing to save some of the most critically endangered species on the planet; the

remaining native forest birds of Hawaii.

Former King of the Hawaiian Forests: The Hawaiian Crow or the ‘Alala is extinct in the wild. Photo courtesy of the San Diego Zoo. |

Mongabay: Tell our readers about the history of the Hawaii Endangered Bird Conservation Program.

Alan Lieberman: As the world’s most isolated island chain, the fragile native flora and fauna of Hawaii

have long been vulnerable to introduced species and the effects of man.

Environmental changes brought by modern man, though, accelerated the damage and by the 1970’s the

local extinctions were happening at an alarming rate. Nothing seemed to stop the downward spiral. The

State of Hawaii established a captive breeding facility for native Hawaiian birds, but they were not

succeeding in their efforts.

At that point in time, considerable interest centered around the Hawaiian Crow or “‘Alala,” viewed as a

keystone species of the native Hawaiian forests. However, there was great dispute among local

conservation interests on the best strategy for saving the remaining ‘Alala. The matter was eventually

settled by bringing in a “non-Hawaiian” party in to resolve the dispute and bring fresh expertise. The Fish

and Wildlife Service contracted The Peregrine Fund of Idaho to help with the ‘Alala. Though The Peregrine

Fund was a raptor conservation organization (hawk and eagles), they were able to reach out to other

groups, including the San Diego Zoo (which has expertise in working with passerine or “perching birds” like

crows and ravens) to assist with this project.

An Extinction Gallery: The Hawaii Mamo, last recorded in 1899; the O’u, last sighted in the 1980s; the Greater Akialoa, not seen since the end of the 19th Century; the Black Mamo, last sighted on Molokai in 1907; the Lesser Akialoa, last sighted in 1967; and the Oahu Akepa, last sighted on Oahu in 1980’s. For a complete list of extinct Hawaiian Birds: http://www.birdinghawaii.co.uk/extinctbirdarticle2.htm.

Mongabay: Please tell our readers about the species that you are working with at the Hawaiian Endangered

Bird Conservation Program:

Last sighted in 1860, the extinct Oahu O’O. All paintings are by F.W. Frohawk, a famous Hawai’i bird collector and artist from the 19th Century, unless otherwise stated.  Last sighted in the 1990’s the “Kamao,” or large Kauai thrush.  The critically endangered “Puaiohi” or small Kauai thrush. Photo courtesy of the San Diego Zoo.  The state bird of Hawaii, the Nene. Photo Courtesy of the Hawaiian Audubon Society |

Alan Lieberman: In addition to the ‘Alala which is extinct in the wild, our Hawaiian work also centers

around the captive breeding of three other critically endangered forest bird species: The Puaiohi or Small

Kauai Thrush, the Maui Parrotbill and the Palila. These species are considered to be at great risk and it is

thought that their best hope for survival may be through captive breeding and management. To save these

bird species, we have established two captive breeding centers, one on the Big Island of Hawaii and the

other on Maui.

In addition, we also continue to work with the Hawaiian Goose or “Nene,” Hawaii’s State Bird. Though the

Nene is still endangered, in many ways this bird species represents a great conservation success story: In

the 1950’s there were less then 30 Nene known to exist; now there are over 1,000 Nene in captivity and

nearly 2,000 birds in the wild.

Mongabay: As mentioned, there has been a lot of interest in the ‘Alala or Hawaiian Crow; please tell our readers a little more about this bird.

Richard Switzer of the Hawaii Endangered Bird Conservation Program: The ‘Alala is unique among the

Pacific Island crow species, in that it is more closely related to ravens and is much larger then other crow

species found in the region. The ‘Alala is more monogamous than most crows, more intelligent, and evolved

to fill the ecological role of “monkey” in the native Hawaiian forests. The Hawaiian Islands lacked typical

raven food, large animal carcasses to scavenge. Unique among the world’s ravens, the ‘Alala evolved into a

“fruit eating specialist.” And, in this role, the bird played a huge part in the Hawaiian forest ecosystem since

it was one of the primary agents for seed dispersal in the native Hawaiian forests. In a real sense, the other

Hawaiian bird species and the island’s forests depended on this bird.

But as Hawaii’s native forests shrank, so did the ‘Alala’s numbers. By the early 1990s the population was

down to 20 known birds, before intensive captive breeding efforts started to reverse the decline. The last

wild ‘Alala was seen in 2002, but thanks to captive breeding, a population of more than ninety birds is now

spread between our two conservation facilities in Hawaii.

Mongabay: Why have Hawaiian birds, like the ‘Alala, been so vulnerable to the effects of man?

Richard Switzer: The Hawaiian birds evolved with the absence of mammalian predators and were very

susceptible to the predation of introduced rats, cats, dogs, mongooses, etc. Man also brought feral pigs and

ungulates like goats, deer, sheep, which destroyed much of the native Hawaiian forest plant species upon

which birds like the ‘Alala depend.

And when modern man arrived from the West they brought barrels of fresh drinking water shipboard and in

the process introduced mosquito larvae to the formerly pristine islands of Hawaii. In turn, poultry carried

avian malaria to Hawaii, which the mosquitoes transmitted and to which the native forest birds of Hawaii had

no immunity or defense. The majority of native forest bird species cannot survive in the remaining lower

altitude forests (below 5000 feet above sea level) where the mosquitoes now proliferate.

Thanks to avian malaria, waves of new coming settlers to Hawaiian soon found the remnant forests

denuded of any wild birds. In their absence, these settlers brought new bird species to the islands, filling the

gap left by the demise of the native bird populations.

Birds species now common to Hawaii, but not native to the Islands: The Red Crested Cardinal of Brazil, the Common Mynah and the Zebra Dove of South East Asia. Photos courtesy of the Hawaiian Audubon Society.

Mongabay: Using the ‘Alala as an example, have conditions changed in Hawaii that will allow this bird

species to be returned to the wild? Or has time simply passed by the ‘Alala and the other native Hawaiian

forests birds?

Richard Switzer: That is a very hotly debated topic at the moment. The ‘Alala perished in the wild primarily

due to habitat destruction, disease, and the effects of introduced predators. Successful reintroduction of the

‘Alala will depend upon very intensive habitat management and we are in the process of reviewing potential

release sites. We must learn from the reintroduction efforts in the early 1990s, when captive raised birds

were released, without fully satisfying the bird’s environmental needs or ameliorating the full scope of their

threats. If we simply release ‘Alala into the “wild” without intensive management, we will once again watch

the reintroduced birds “fail one by one.” Evolving without ground-based predators, the ‘Alala suffer from a

condition of “ecological naivety”. For instance, when fledglings ‘Alala came out of the nest in pristine native

Hawaii, they had no reason to fear any ground-based predation. That has, of course, changed.

Compounding problems for the ‘Alala, feral cats not only prey on young ‘Alala, but also spread a disease to

which the birds are extremely vulnerable, toxoplasmosis. And with introduced ungulates like goats and pigs

actively destroying the native forest’s under-story, we now have evidence that another native (and

endangered) Hawaiian bird, the Hawaiian Hawk or “Io” was able to pick off young ‘Alala due to lack of

shelter from a native predator.

We will have to fence, monitor, and patrol the initial release sites from feral ungulates, cats, etc to give the

birds’ a fighting chance in the wild. Ecological restoration is workable, but it is a complex matter. Returning

the ‘Alala to the wild is not as easy as “simply releasing them from their cages.” This year we had are most

successful ‘Alala breeding season to date and we now feel that we have a sufficient captive population that

we can attempt to restore the ‘Alala, but only to managed forest habitat in Hawaii.

The Puaiohi, or small Kauai thrush, represents a similar restoration story. So far, we have released 200

Puaiohi into the native forests of Kauai, but these successful reintroductions came only after a similar

learning curve. And the same can be said for our ongoing work with the Palila and Maui Parrotbill.

Two other Hawaiian forest bird species under intensive management: the Palila and the Maui Parrotbill But help came too late for the Po’ouli, the last known bird passed in 2004 (third photo from left). Photos courtesy of the San Diego Zoo.

Richard Switzer: I would not say that the world for the ‘Alala or the other Hawaiian forest birds has come

and gone, but the survival of these birds in the wild will initially depend upon intensive human intervention

and management. Their world is not gone, but it has certainly changed.

Hope for future generations: some of the 2010 Alala. Photo courtesy of the San Diego Zoo |

Mongabay: Why do the Hawaiian forest bird species warrant all this effort and attention?

Alan Lieberman: Those of us in the developed world tend to look askance at the developing world’s

environmental challenges, but no other area on the planet has suffered the same rate extinction as those

that have befallen the Hawaiian forest birds, and these are our own American species. If we in the

developed world are going to ask the people of Brazil, Indonesia, India, China, Kenya, Madagascar, (etc) to

better manage their environmental issues, aren’t we obligated to walk our talk through example? Like the

rest of the planet’s biodiversity, the native forest birds of Hawaii represent a shared global-heritage; it is

critical that we do our part to save the world’s endangered species.

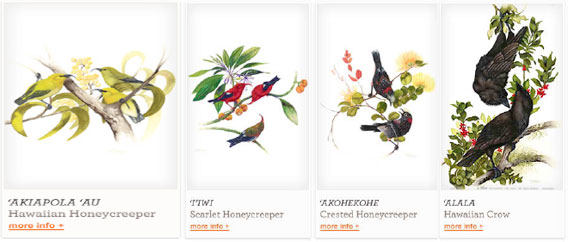

But it’s not to late to save these species. Help support Hawaiian Bird Conservation through Hawaiian Native Bird Conservation Prints: Available online at the San Diego Zoo.