Burying your head in the sand is one approach to dealing with environmental complaints, but judging from the successes of Greenpeace’s recent campaigns, it probably isn’t a very effective one for Indonesian forestry firms, which are competing in an international marketplace where environmental issues are a real and growing concern.

Peatlands destruction in Indonesian Borneo. Photo by Rhett Butler.

Last week Indonesian immigration officials in Jakarta blocked Greenpeace director John Sauven from entering the country. Sauven, who two weeks earlier had obtained the proper business visa for his visit from the Indonesian embassy in London, was scheduled to convene with his team in Jakarta, travel to the island of Sumatra, and meet with officials and Indonesian businesses at a forestry conference. The following day, Greenpeace campaigner Andrew Tait was harassed by unknown individuals who attempted to serve him with a deportation warrant.

Besides creating confusion for travelers over whether immigration officials in Jakarta will honor business visas obtained at embassies abroad, Sauven’s deportation and Tait’s harassment raise a more interesting question: why is Indonesia afraid of Greenpeace?

Greenpeace is an environmental group. While it’s not small — Greenpeace’s budget is around $250 million a year across all of its member organizations — it certainly poses no security threat to Indonesia. Despite claims by some local politicians that it is a terrorist group, Greenpeace has never called for violence and in fact prides itself on non-violent confrontation. So why the fear?

Being the lowest cost producer of wood pulp doesn’t make a lot sense if it costs Indonesia its most valuable assets. (Forest in Indonesian New Guinea, where pulp and paper firms are eying expansion). Indonesia’s pulp and paper trade association (APKI) recently threatened legal action against CIFOR, a forestry research institution, when it reprinted text from a speech given by President SBY, which attributed deforestation in Sumatra to pulp and paper production. |

The answer lies in Greenpeace’s increasing effectiveness as a campaign organization. Companies and industries face severe pressure in the marketplace once they are targeted by Greenpeace. There’s plenty of evidence: in the past five years, Greenpeace campaigns have caused dramatic changes in how soy and cattle are produced in the Brazilian Amazon. Un Indonesia the group pushed PT SMART [owned by Golden-Agri Resources (GAR)], the country’s largest palm oil producer, to adopt a strict forest policy. Greenpeace is now focusing on Indonesia’s pulp and paper industry, which is blamed for large-scale destruction of rainforests and peatlands in Sumatra. Specifically, they are targeting Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), one of the country’s largest and most controversial fiber suppliers.

There are strong indications that Sauven’s deportation and Tait’s harassment were the result of influence from private sector interests, rather than a new official policy against environmental campaigners (Sauven intended to meet with government officials about supporting Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s pledge to dramatically reduce deforestation). As we’ve seen from recent efforts to undermine President Yudhoyono’s moratorium on new forest concessions and stepped-up rhetoric against environmental groups (curiously, Sauven’s deportation coincided — to the day — with the launch of an anti-Greenpeace web site by a group that advocates on behalf of the Indonesian pulp and paper industry), the business-as-usual approach to forestry in Indonesia is at risk. Reforms needed to enact President Yudhoyono’s vision of a low carbon economy are a direct threat to firms that rely on intimidation of local communities, corrupt and unaccountable institutions, public complacency, lack of transparency around land use, and large-scale forest destruction.

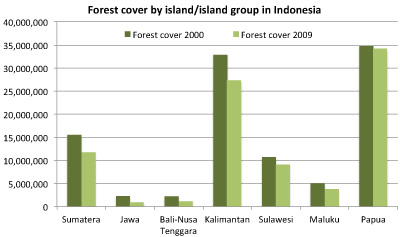

All figures in hectares |

Facing an uncertain future, the oligopolies are now fighting back. These firms seem to believe that their model—perfected under 30-plus years of dictatorial rule by General Suharto and designed to personally enrich at the expense of most Indonesians—is politically sustainable. But while they may find short-term success in silencing civil society in Indonesia, forestry companies are today competing in a global marketplace where issues like social and environmental stewardship actually matter. Yes, a developer may be able to maximize profits today by converting thousand-year-old rainforest into an oil palm plantation, but what is the long-term strategy? What happens if Brazil makes good on its plan to establish more than 5 million hectares of oil palm plantations on non-forest land? Will the most attractive markets discriminate against palm oil that is produced in ways that result in social conflict and environmental degradation?

Markets are already changing. It is increasingly clear that consumer-facing companies, especially in the West but also Brazil, do not want to be associated with social conflict and deforestation. These represent reputational risks to big companies. For example Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer, PT SMART, lost tens of millions of dollars in business after being dropped by Unilever, Kraft, and Nestle when linked to deforestation and conversion of peatlands. The company has since adopted a new forest policy that is among the strongest in Indonesia, prohibiting the conversion of peatlands and rainforests, and requiring free, prior, and informed consent from communities.

Is Indonesia losing its most valuable assets? (05/16/2011) Deep in the rainforests of Malaysian Borneo in the late 1980s, researchers made an incredible discovery: the bark of a species of peat swamp tree yielded an extract with potent anti-HIV activity. An anti-HIV drug made from the compound is now nearing clinical trials. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and help improve the lives of millions of people. This story is significant for Indonesia because its forests house a similar species. In fact, Indonesia’s forests probably contain many other potentially valuable species, although our understanding of these is poor. Given Indonesia’s biological richness — Indonesia has the highest number of plant and animal species of any country on the planet — shouldn’t policymakers and businesses be giving priority to protecting and understanding rainforests, peatlands, mountains, coral reefs, and mangrove ecosystems, rather than destroying them for commodities? |

These shifts are also happening outside of Indonesia. In Brazil, soy producers and cattle ranchers—who account for the vast majority of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon—have recently implemented safeguards after protests from some of their largest customers. Brazil’s cattle industry—the largest in the world—was brought to its knees virtually overnight when Walmart, Nike, and Adidas said they didn’t want their leather and beef tainted by deforestation and labor abuses. Maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Brazil has been able to grow its economy while cutting deforestation: since 2004 Brazil’s annual deforestation rate in the Amazon has fallen 80 percent while its per capita GDP has surged nearly 40 percent.

There’s no reason Indonesia can’t do the same. It won’t be easy, but a smart development model—like that pushed by Yudhoyono—is one that capitalizes on Indonesia’s unique and valuable assets rather than degrading and destroying them.

Related articles

Paper suppliers risk damaging Indonesia’s reputation, argues report

(10/07/2011) Indonesia needs to re-evaluate forest areas and peatlands granted for pulp and paper plantations to reduce the risk of damaging the international reputation of its forest products and undermining its commitment to greenhouse gas emissions reductions, argues a new report published by an Indonesian activist group.

Indonesian president vows to dedicate remainder of term to protecting rainforests

(09/27/2011) Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono on Tuesday vowed to dedicate the last three years of his presidency to ‘deliver enduring results that will sustain and enhance the environment and forests of Indonesia’, reports the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), which hosted his speech. President Yudhoyono emphasized the importance of forests in mitigating climate change, safeguarding biodiversity, and helping alleviate poverty. He said conserving and sustainably managing Indonesia’s forests is not necessarily at odds with growing the economy.

(07/27/2011) Indonesia’s forests were cleared at a rate of 1.5 million hectares per year between 2000 and 2009, reports a new satellite-based assessment by Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI), an NGO. Expansion of oil palm and wood-pulp plantations were the biggest drivers of deforestation, yet account for a declining share of the national economy. The study, which compared year 2000 data with 2009 Landsat images from NASA, found that Indonesia’s forest cover declined from 103.32 million hectares to 88.17 million hectares in ten years. Since 1950 Indonesia lost more than 46 percent of its forests.

(05/16/2011) Deep in the rainforests of Malaysian Borneo in the late 1980s, researchers made an incredible discovery: the bark of a species of peat swamp tree yielded an extract with potent anti-HIV activity. An anti-HIV drug made from the compound is now nearing clinical trials. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and help improve the lives of millions of people. This story is significant for Indonesia because its forests house a similar species. In fact, Indonesia’s forests probably contain many other potentially valuable species, although our understanding of these is poor. Given Indonesia’s biological richness — Indonesia has the highest number of plant and animal species of any country on the planet — shouldn’t policymakers and businesses be giving priority to protecting and understanding rainforests, peatlands, mountains, coral reefs, and mangrove ecosystems, rather than destroying them for commodities?

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.