The moratorium on clearing Amazon rainforest for soy farms in Brazil appears to be maintaining its effectiveness for a fifth straight year, reports the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries (ABIOVE).

Forest monitoring undertaken by ABIOVE found soy on 11,698 hectares of forest land deforested after July 2006, the cut-off date for the moratorium. By comparison, some 4.2 million hectares of forest were cleared across the Amazon biome during the same period. Of that, nearly 370,000 hectares are located in soy-producing municipalities, indicating that soy cultivation has directly driven only a small fraction (3 percent) of deforestation since the moratorium was enacted.

The soybean moratorium was a direct product of a Greenpeace campaign launched in 2006. The campaign linked soy-based feed used to fatten chickens for fast-food chains to deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The main target—McDonald immediately demanded its suppliers provide deforestation-free soy, presenting the industry with a daunting dilemma: move towards environmental respectability or lose one of its biggest, and most influential, customers. The largest soy players—whose vast portfolio of commodities are sold globally—chose the former, agreeing to a moratorium on soy grown on newly deforested lands that has changed the way commodities are produced in the Amazon. The moratorium, which was established by ABIOVE and the National Association of Cereal Exporters (ANEC), has been extended every year since. Soy producers who fail to abide by the moratorium cannot sell their product to ABIOVE or ANEC, which account for more than 90 percent of Brazil’s domestic market.

|

|

However, despite the update from ABIOVE, Greenpeace warned that the moratorium may be endangered by proposed changes to Brazil’s forest code, which requires property owners maintain forest cover on their lands. Greenpeace noted that Brazil’s satellite monitoring system has detected a sharp increase in deforestation in soy-producing states over the past 12 months, which it says is a consequence of speculation that the forest code will be relaxed.

“[Forest Code] changes would allow an amnesty for past forest crimes, creating an incentive for illegal activity now and leading to an increase in deforestation before the law has even been changed. This can only get worse if the proposed amendments to the Forest Code go through,” wrote Sarah Shoraka in a post on Greenpeace’s blog. “That’s why we are not celebrating the moratorium’s fifth year. Instead we are using the anniversary as an opportunity to make the moratorium even stronger. The threat to the Forest Code means that the moratorium becomes even more important as a tool to drive the changes needed in Brazil to reach our zero deforestation goal.”

Greenpeace added that the private sector—especially export-oriented businesses—are worried that changes to the forest code could tarnish their image abroad if deforestation increases.

“Companies supporting the moratorium have also expressed their concerns about changes to the Forest Code publicly for the first time. Their voices have added to those of scientists, campaigning organizations and the majority of the Brazilian public, showing that concerned companies are capable of trading with Brazil while keeping their products free from deforestation.”

Paulo Adario, Director of Greenpeace-Brazil, added that the moratorium has proved that agricultural production can grow without deforestation.

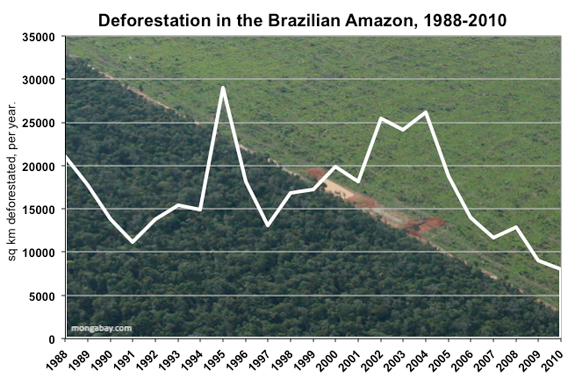

“Over the five years of the moratorium, deforestation of the Amazon has fallen and soybean exports have increased,” he said. “It is now necessary to strengthen the commitment and create permanent governance bases to provide the market with a guarantee that its demand for zero deforestation in the [supply] chain is met.”

Related articles

Despite moratorium, soy still contributes indirectly to Amazon deforestation

(07/15/2011) Soy expansion in areas neighboring the Amazon rainforest is contributing to loss of rainforest itself, reports a new study published in Environmental Research Letters.

Brazilian senator: Forest Code reform necessary to grow farm sector

(07/06/2011) Over the past twenty years Brazil has emerged as an agricultural superpower: today it is the largest exporter beef, sugar, coffee, and orange juice, and the second largest producer of soybeans. While much of this growth has been fueled by a sharp increase in productivity resulting from improved breeding stock and technological innovation, Brazil has benefited from large expanses of available land in the Amazon and the cerrado, a grassland ecosystem. But agricultural growth in Brazil has always been limited — at least on paper — by its environmental laws. Under the country’s Forest Code, landowners in the Amazon must keep 80 percent of their land forested.

Dutch buy first ‘responsible’ soy sourced from the Amazon

(06/08/2011) The Dutch food and feed industry has bought the first soy produced under the principles of the Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS), a body that aims to bring more socially and environmentally sustainable soy to market.

Moratorium on Amazon deforestation for soy production proving effective

(03/06/2011) The Brazilian soy industry’s moratorium is proving effective at slowing deforestation for soy production in the Amazon rainforest, reveals a new study published in the journal Remote Sensing.

Brazil’s largest national bank signs zero deforestation pact for Amazon soy

(12/03/2010) Banco do Brasil, Brazil’s largest state-owned bank, announced it has joined a zero deforestation pact for soy grown in the Amazon. The bank will now require farmers applying for credit to certify the origin of their soybeans.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

Amazon soy moratorium extended

(07/08/2010) Brazilian soy farmers have extended their moratorium on Amazon deforestation for another year, reports Greenpeace.

Ending deforestation could boost Brazilian agriculture

(06/26/2010) Ending Amazon deforestation could boost the fortunes of the Brazilian agricultural sector by $145-306 billion, estimates a new analysis issued by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a group pushing for U.S. climate legislation that includes a strong role for forest conservation. The analysis, which follows on the heels of a report that forecast large gains for U.S. farmers from progress in gradually stopping overseas deforestation by 2030, estimates that existing Brazilian farmers could see around $100 billion from higher commodity prices and improved access to markets. Meanwhile landholders in the Brazilian Amazon—including ranchers and farmers—could see $50-202 billion from carbon payments for forest protection.

Large-scale soy farming in Brazil pushes ranchers into the Amazon rainforest

(04/28/2010) Industrial soy expansion in the Brazilian Amazon has contributed to deforestation by pushing cattle ranchers further north into rainforest zones, reports a new study published the journal Environmental Research Letters.

Soy in the Brazilian Amazon

Soy in the Brazilian Amazon