Collared puffbird (Bucco capensis) in Yasuni National Park in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

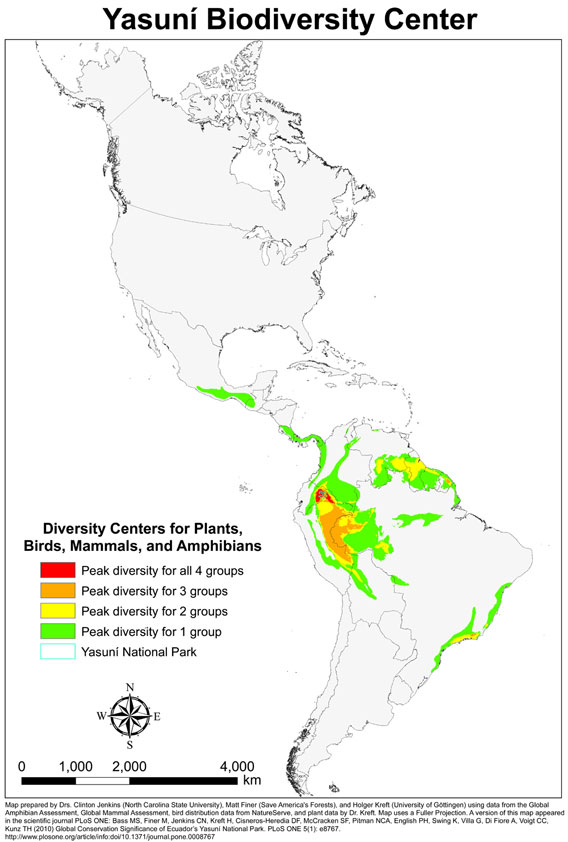

A new map highlights the importance of conserving Yasuni National Park as the most biodiverse ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere, and maybe even on Earth. Scientists released the map to coincide with the United National General Assembly in support of a first-of-its-kind initiative to save the park from oil exploration through international donations to offset revenue loss. Known as the Yasuni-ITT Initiative, the plan, if successful, would protect a 200,000 hectare bloc in Yasuni National Park from oil drilling in return for a trust fund of over $3 billion.

“The map indicates that Yasuni National Park is part of a small, unique zone with the maximum biological diversity in the Western Hemisphere,” explained Clinton Jenkins, lead designer of the map and Research Scholar at North Carolina State University, in a press release.

The map shows that eastern Ecuador (the location of Yasuni) and northeastern Peru have the highest number of species in the hemisphere based on data on birds, mammals, amphibians, and plants. To highlight this point, researchers have found more tree species (655 to be exact) in a single hectare in Yasuni than in all of the US and Canada combined. Yasuni also contains the highest biodiversity of reptiles and amphibians in the world with 271 species. But bugs may win the day yet: according to entomologist Terry Erwin, a single hectare of rainforest in Yasuni may contain as many as 100,000 unique insect species. This estimate, if proven true, is the highest per unit area in the world for any taxa, plant or animal.

“Yasuni is an international treasure—perhaps the biologically richest place on Earth. Its loss would be a tragedy for Ecuador and, indeed, peoples worldwide who celebrate the diversity of life,” says Hugo Mogollon, executive director of Finding Species, an NGO that works in Ecuador. “The Yasuni-ITT Initiative is pioneering. It is a serious effort to keep megadiverse forest intact, coming straight from the office of the President of Ecuador. Governments of the region and around the world should really want to support this.”

Launched in 2007, the Ecuadorian government has promised to leave vast oil reserves of an estimated 846 million barrels of oil untapped in bloc ITT of Yasuni National Park if international donors are willing to contribute $3.6 billion, or about half the market value of the oil lying underneath the area. The Yasuni fund would provide monies for renewable energy projects, as well as social programs, research initiatives, conservation, and reforestation projects. However despite support from many scientists and conservation organizations the initiative has had a difficult time raising funds, a situation not helped by the fact that the fund launched one year before the global recession.

The initiative took a severe blow earlier this year when Germany bowed out of supporting the program. A statement from German Federal Minister Dirk Niebel said the initiative was “interesting and innovative”, but there were too many unanswered questions regarding the program.

“What lacks are a uniform justification context, a clear goal structure, and concrete statements as to how a permanent renunciation on oil extraction could be guaranteed in the Yasuni area. Furthermore, no other donor has as yet agreed to support the initiative. It further appears doubtful whether this approach really offers comparative advantages over the numerous alternative solutions currently discussed (e.g. REDD). Moreover, the support of the ITT initiative might set precedence with regards to compensation claims by oil-producing countries in climate negotiations,” Niebel wrote.

Yet if the initiative is supported, the Ecuadorian government says it would preserve Yasuni in perpetuity from oil drilling and keep an estimated 410 million tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere at a time when many governments have proven lackluster in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But Ecuador’s President, Rafael Correa, has said that if the fund does not receive its first $100 million by this December, he will cancel the initiative and oil drilling will proceed.

Oil is currently Ecuador’s biggest exporter and the nation’s economy remains largely dependent on the fossil fuel. But oil has also brought the nation trouble with pollution, disease, forest destruction, and conflict with indigenous people.

Map by Matt Finer, Clinton Jenkins, and Holger Kreft. Click to enlarge.

Related articles

Germany backs out of Yasuni deal

(06/13/2011) Germany has backed out of a pledge to commit $50 million a year to Ecuador’s Yasuni ITT Initiative, reports Science Insider. The move by Germany potentially upsets an innovative program hailed by environmentalists and scientists alike. This one-of-a-kind initiative would protect a 200,000 hectare bloc in Yasuni National Park from oil drilling in return for a trust fund of $3.6 billion, or about half the market value of the nearly billion barrels of oil lying underneath the area. The plan is meant to mitigate climate change, protect biodiversity, and safeguard the rights of indigenous people.

Oil, indigenous people, and Ecuador’s big idea

(11/23/2010) Ecuador’s big idea—potentially Earth-rattling—goes something like this: the international community pays the small South American nation not to drill for nearly a billion barrels of oil in a massive block of Yasuni National Park. While Ecuador receives hundred of millions in an UN-backed fund, what does the international community receive? Arguably the world’s most biodiverse rainforest is saved from oil extraction, two indigenous tribes’ requests to be left uncontacted are respected, and some 400 million metric tons of CO2 is not emitted from burning the oil. In other words, the international community is being asked to put money where its mouth is on climate change, indigenous rights, and biodiversity loss. David Romo Vallejo, professor at the University of San Francisco Quito and co-director of Tiputini research station in Yasuni, recently told mongabay.com in an interview that this is “the best proposal so far made to ensure the protection of this incredible site.”

(10/28/2010) Although most Americans have likely seen photos and videos of the world’s largest rainforest, the Amazon, they will probably never see it face-to-face. For many, the Amazon seems incredibly remote: it is a dim, mysterious place, a jungle surfeit in adventure and beauty—but not a place to take a family vacation or spend a honeymoon. This means that the destruction of the Amazon, like the rainforest itself, also appears distant when seen from Oregon or North Carolina or Pennsylvania. Oil spills in Ecuador, cattle ranching in Brazil, hydroelectric dams in Peru: these issues are low, if not non-existent, for most Americans. But a visit to the Amazon changes all that. This was recently confirmed to me when I traveled with American college students during a trip to far-flung Yasuni National Park in Ecuador. As a part of a study abroad program with the University of San Francisco in Quito and the Galapagos Academic Institute for the Arts and Sciences (GAIAS), these students spend a semester studying ecology and environmental issues in Ecuador, including a first-time visit to the Amazon rainforest at Tiputini Biodiversity Station in Yasuni—and our trips just happened to overlap.