Deforestation worsens famine in Africa, but drylands restoration could help.

Millions of people across the Horn of Africa are suffering under a crippling regional drought and tens of thousands have died during the accompanying famine. Refuge camps in Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia are swelling with the hungry.

The best hope in the short-term is food aid and logistical support, but in the longer term, dryland reforestation efforts may help improve food security, argues a new report from the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which links human-caused land degradation, including deforestation, to intensified drought.

“There is a mistaken view that because these are dry areas, they are destined to provide little in the way of food and are simply destined to endure frequent famines, but dryland can and do support significant crop and livestock production. In fact, the famine we are seeing today is mainly a product of neglect, not nature,” states Dennis Garrity, director general of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).

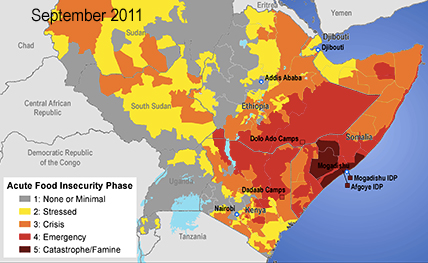

Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) alert for September on the Horn of Africa region |

Recent research by CGIAR’s Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in 25 countries found forests are critical defenses against poverty, providing a quarter of household income for those living in or around them. In particular, agroforestry efforts offer improvements in farm productivity and food security in Africa’s drylands.

Forest resources provide fodder and fertilizer for small farms, which benefit by planting trees on site. When planted as windbreaks, trees fortify the soil against erosion while retaining moisture and nutrients, preventing soil degradation. CGAIR notes “fertilizer trees” that release nitrogen into the soil are restoring farmland in Malawi, Zambia, Kenya, Tanzania, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Some native trees also may serve as livestock fodder when grass is unavailable. Reforestation projects in Ethiopia known as Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) and implemented by the World Bank and World Vision are restoring 2,700 hectares of land to provide timber and improve pasture by reducing soil erosion.

“Forests and trees frequently form the basis of livelihood diversification, risk-minimization and coping strategies, especially for the most vulnerable households such as those led by women. However, deforestation and land degradation have hindered capacities to cope with disasters and adapt to climate variability and change in the long-term,” explains Frances Seymour, director general of the CGIAR’s Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Earlier reforestation programs offer evidence that access to forests increases food security during droughts. In 1983, a program in Niger began transforming 5 million hectares of barren land into agroforests. Experts from ICRAF noted that during Niger’s 2005 drought, farmers who had adopted agroforestry supplemented their diets with fruits and edible leaves from drought-resistant trees, then furthered their defense against hunger by selling timber to purchase other food staples.

“It’s ironic that dryland forests are not front and center in the climate change debate, because climate change is likely to bring more frequent and more severe droughts to dryland areas, and the adaptation challenge for affected communities will be great,” says Seymour. While CGAIR is confident agroforestry can heal degraded landscapes while providing increased food security, the need for reforestation is substantial.

Related articles