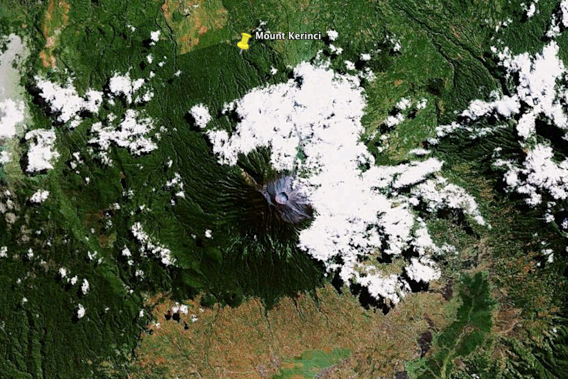

Mount Kerinci, Sumatra’s largest volcano, is a part of Kerinci Seblat National Park. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

We initially reported that Kerinci Seblat National Park has been closed to the public since 2004 due to volcanic activity. However, the park itself is not closed, but only the peak of the volcano, Mount Kerinci, which lies within the park, is.

The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) has drafted a resolution urging the Indonesian government to cancel plans to build four 40-foot wide roads through the countries oldest national park, Kerinci Seblat National Park. According to the ATBC, the world’s largest professional society devoted to studying and conserving tropical forests, the road-building would imperil the parks’ numerous species—many of which are already threatened with extinction—including Sumatra’s most significant population of tigers.

“Scientific studies have demonstrated that increased road access to isolated areas such as Kerinci Seblat National Park increases forest loss and degradation through illegal logging and smallholder encroachment and subsequent human-wildlife conflicts,” explains the resolution, which notes that the road-building would actual be illegal under Indonesian law.

Located in west-central Sumatra, the park’s famed biodiversity—surveys have found over 85 mammals and 370 birds species in the park alone—has led to its recognition as an Important Bird Area, an ASEAN Heritage Site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The 1.4 million hectare park is the largest in Sumatra.

“[The] major proposed development project, involving construction of three ‘disaster-evacuation roads’ and one economic road, would penetrate into core zones of the Kerinci Seblat National Park and dramatically increase human access to these isolated rainforest areas,” according to the ATBC.

Human access would take its toll on the park’s Sumatran tigers (Panthera tigris sumatrae). The subspecies is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN since poaching, decrease in prey, and widespread logging for palm oil and paper products has left only around 500 surviving in the wild. Kerinci Seblat National Park has been one of the bright spots for the Sumatran tiger: here, the population is on the rise. But the ATBC says that could soon change if the roads are built.

Sumatran tiger in captivity. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

“[The roads] will have negative impacts on tiger conservation at Kerinci Seblat, thereby increasing the likelihood of local extinction of its critical tiger population,” reads the resolution.

Furthermore the roads will undercut Indonesia’s commitment at the Global Tiger Recovery Program. Last year 13 tiger range nations, including Indonesia, agreed to double wild tiger populations worldwide by 2022. In May Mahendra Shrestha from Save the Tigers in the US told the AP that the road plans made a “mockery” of Indonesia’s tiger pledge.

The ATBC urges Indonesia to “immediately reject the proposed road network in the heart of Kerinci Seblat National Park”. In addition it says the government should work with local and international scientists to “to identify environmentally sound alternatives for road infrastructure that meet local development aspirations without irreparably damaging the integrity of Kerinci Seblat National Park.”

“There are existing roads through Kerinci Seblat National Park that are used by the public on a daily basis – including three routes from Kerinci District, which is proposing these new routes. […] The key point here is that there are viable alternatives to constructing new routes, that are better for biodiversity and better for people,” Zoe Cullen with Fauna & Flora International’s Indonesia Program told mongabay.com.

While the news of the road construction has focused on tigers in the park, the protected area is home to a number of other globally endangered species. The Critically Endangered Sumatran rhino and Sumatran ground cuckoo—whose populations are both half that of Sumatran tigers—still roam the park, as do Sumatran elephants, Malaysian tapirs, Sunda clouded leopards, sun bears, marbled cats, Sumatran serow (a bizarre ungulate), Sumatran rabbits, Schneider’s pittas, and Salvadori’s pheasants, all of which are threatened with extinction.

The park was also the location of the rediscovery of the Sumatran muntjac, a type of small deer, after having gone unrecorded by science for 78 years. Although researchers are unsure whether the animals is a unique species or subspecies, its rediscovery proved just how much remains hidden in Kerinci Seblat.

Related articles

Road building plan in Sumatran park threatens Critically Endangered tigers

(05/03/2011) A plan to build four wide roads through Kerinci Seblat National Park in the Indonesian island of Sumatra threatens one of the world’s most viable populations of the Critically Endangered Sumatran tiger subspecies (Panthera tigris sumatrae), reports the AP. Less than 500 Sumatran tigers remain in the wild with the population continuing to decline due to habitat loss from palm oil and paper plantations, poaching, and prey declines.

Camera traps capture tiger bonanza in Sumatra forest slated for logging

(05/09/2011) Camera traps set in an area of forest slated for logging for paper production captured photos of a dozen critically endangered Sumatran tigers, reports the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF).

Major paper company clear-cutting key tiger habitat

(04/19/2011) A pulp supplier for a major paper company is clearing natural forest in a wildlife corridor in central Sumatra, alleges a new investigation conducted by Eyes on the Forest, a coalition of environmental groups.