This article was originally posted as Indonesia’s Ambitious Forest Moratorium Moves Forward on the World Resources Institute’s web site. It has been reposted here with the permission of WRI.

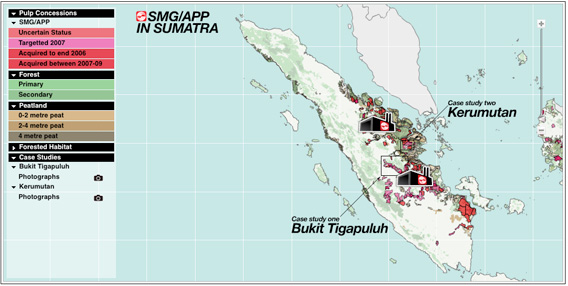

Click image to enlarge

On May 20, 2011, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono signed a Presidential Instruction (“decree”) putting into effect a two-year moratorium on issuing new permits for use of primary natural forest and peatland.

The highly anticipated moratorium is part of a broader $1 billion Indonesia-Norway partnership to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (known as REDD+).

According to government statements, the decree applies to between 64 and 72 million hectares of primary forest and peatland, shown in a map attached to the decree. The decree highlights governance as a key area for improvement, critical in addressing the underlying causes of forest loss. The President calls on ministries and agencies to work together nationally and locally to implement the moratorium.

It is difficult to assess the likely effectiveness of the moratorium in achieving its goal of reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, since the decree includes a number of exemptions (such as cases in which licenses are pending) without providing details on the exempted areas’ location or size.

No logging sign in West Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett Butler |

In order for the public to fully assess the impact of the decree, the government would need to make all exemptions public in such a way that a quantitative spatial analysis can be independently prepared and published. Only with this information can the various partners in Indonesia’s efforts to reduce GHG emissions see whether the spirit of the decree is being met.

In the meantime, this article provides a summary of how key elements are addressed, identifies unanswered questions to be further explored once the digital maps and additional information are publicly available, and suggests priority actions for the two-year moratorium period that can produce lasting benefits to Indonesia’s forests and the people and businesses that depend on them.

The moratorium makes progress in some key areas…

- Despite stiff opposition from advocates of business as usual, a moratorium has been signed and issued.

- It highlights the importance of improved governance.

- It recognizes the importance of ministries and agencies working together to make implementation of the decree successful.

- It includes a map of areas that should not be deforested. The representation of this decree in map form makes it easier for stakeholders to carry out monitoring and support law enforcement.

…but some important issues remain:

- Areas of secondary forest are not covered. These are widespread and valuable for carbon, biodiversity and livelihoods.

- There is no mention of the Minister of Mines and Energy in the decree, and it is not clear how permits for non-exempted mining activities (i.e. coal and minerals) will be addressed. The Ministry of Agriculture is also not mentioned in the decree.

- Community-based forest management and other sustainable activities that do not result in forest conversion are not included in the exemptions.

- No information is provided on the extent and location of existing permits that are exempted from the moratorium.

- It is unclear what will happen with the many permits that may have been issued illegally.

What is addressed in the Presidential Decree?

The Presidential Decree gives instructions to specific government agencies regarding a two-year suspension of new permits on areas of primary natural forest and peatland shown in an attached “Indicative Map of New License Suspension” (Indicative Map).

Click image to view map.

The Presidential Decree addresses key elements in the following ways:

Objectives: Does the preamble clarify the objectives of a temporary suspension of new permits to achieve long term improvements in land use planning and permitting processes

The decree itself states that the objective is to balance economic, social, and cultural development and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. The explicit inclusion of governance is notable and should be applauded, as this starts to get to the root causes of Indonesia’s high rates of forest loss. It will be especially important in the coming months to reach agreement on what specific improvements in governance are needed most and how these improvements can be achieved.

|

Recent related articles Indonesia’s anti-mafia unit seeks to reopen $115 billion illegal logging case (06/08/2011) Indonesia’s Anti-Mafia Law Task Force asked authorities Tuesday to reopen an investigation into illegal logging that may have cost the Indonesian state $115 billion. Indonesian president urges other countries not to buy illegally logged wood from Indonesia (06/08/2011) Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono asked consuming countries to join the fight against illegal logging in Indonesia, reports the Jakarta Globe. Indonesia’s moratorium map has errors, says government (06/03/2011) The map underpinning Indonesia’s moratorium on new concessions in primary forests and peatlands is “inaccurate”, an Indonesian forestry official told The Jakarta Post. Interview with Indonesian climate official on rainforest logging moratorium (06/03/2011) In May, Indonesia President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono issued a presidential instruction laying out the specifications for a two-year moratorium on new concessions in primary forests and peatlands. The moratorium aims to create a window for Indonesia to enact reforms needed to slow deforestation and forest degradation under its Letter of Intent with Norway, which would pay the Southeast Asian nation up to a billion dollars for protecting forests. Lack of clarity complicates Indonesia’s logging moratorium (05/27/2011) Lack of clarity makes it difficult to assess whether Indonesia’s moratorium on new logging concessions in primary forest areas and peatlands will actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation, according to a new comprehensive assessment of the instruction issued last week by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The analysis, conducted by Philip Wells and Gary Paoli of Indonesia-based Daemeter Consulting, concludes that while the moratorium is “potentially a powerful instrument” for achieving the Indonesian president’s goals of 7 percent annual growth and a 26 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from a projected 2020 baseline, the language of the moratorium leaves significant areas open for interpretation, potentially offering loopholes for developers. Indonesia’s moratorium allows mining in protected forests (05/23/2011) Indonesia’s mining industry expects the just implemented moratorium on new forestry concessions in primary forests and peatlands to open up protected areas to underground coal and gold mining, reports the Jakarta Globe. Indonesia’s moratorium disappoints environmentalists (05/20/2011) The moratorium on permits for new concessions in primary rainforests and peatlands will have a limited impact in reducing deforestation in Indonesia, say environmentalists who have reviewed the instruction released today by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The moratorium, which took effect January 1, 2011, but had yet to be defined until today’s presidential decree, aims to slow Indonesia’s deforestation rate, which is among the highest in the world. Indonesia agreed to establish the moratorium as part of its reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) agreement with Norway. Under the pact, Norway will provide up to a billion dollars in funds contingent on Indonesia’s success in curtailing destruction of carbon-dense forests and peatlands. Indonesia signs moratorium on new permits for logging, palm oil concessions (05/19/2011) After five-and-a-half months of delay due to political infighting, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono finally signed a two-year moratorium on the granting of new permits to clear rainforests and peatlands, reports Reuters.

Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work? (12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources. |

Definitions: Are terms clear and consistent with achieving the stated objectives

The decree does not include definitions of terms. The decree refers to primary natural forest and peatland, but not secondary forest. Large areas of secondary forest, with high carbon content and important biodiversity, will therefore likely not be covered by the decree.

The terms primary natural forest and peatland have not been defined in Indonesian law. In this context they have been interpreted as descriptions of vegetative cover and soil characteristics, as distinct from legal designations. The decree also refers to legal designations such as conservation forest, protected forest, and production forest, which have been previously defined in Indonesia’s 1999 Forestry Law. Media reports suggest there is ongoing confusion regarding whether or not primary natural forest refers to a legal designation.

Data: Are the data and maps that will be used or created to determine the areas impacted by the moratorium accurate and adequate

There is insufficient information on the data and methods used to develop the Indicative Map, and indeed, on who produced it. This map shows peatland and primary forests, yet there are no definitions of these terms. It is also not clear which areas are under which forms of protection, and whether any information on existing or already exempted permits was used to generate the map. Crucially, no information is provided on the extent, location, and status of existing and exempted permits.

A more detailed analysis can be conducted only once the digital maps, source data layers, associated methods, and accurate information on the extent, location, and status of existing and already exempted permits, are made publicly available.

Permits: Which permits are included and excluded from the moratorium?

The moratorium applies to “new permits” (e.g. for the clearing of land to start oil palm, timber or other large estate crops) in the areas specified by the Indicative Map, with a considerable number of notable exemptions, including those for:

- forest area release and use permits that have been approved in principle by the Ministry of Forestry;

- geothermal, oil and gas, electricity, rice and sugar cane development;

- extension of existing and valid forest use permits (e.g. logging permits); and

- ecosystem restoration concessions.

No exemptions are provided for the multiple types of use or management rights that can be issued to communities, even though community based forest management and monitoring has been recognized as an effective strategy for achieving sustainable forest management and balancing economic, social, and environmental development goals.

The types of permits which will not be exempted include loan use and business permit use for timber in natural forests issued by Ministry of Forestry, lease rights and use rights issued by the National Land Agency, and recommendations for and location permits issued by Governors and Regents/Mayors. There is no mention of exemptions or inclusion of forest use for mineral or coal mining.

The process for determining the validity of existing forest use permits is unclear. It is also not clear what the implications are for companies that have existing location permits (which are exempted) but not business use permits (called HGU permits). These existing permits may cover millions of hectares (an estimate from Daemeter Consulting is at least three million hectares).

Agencies: Which government agency is responsible for producing the relevant maps associated with the moratorium

Instructions to suspend issuing permits apply to all areas in the Indicative Map. This applies to the Ministry of Forestry, National Land Agency, as well as to all Governors, Regents and Mayors. The Minister of Interior is instructed to coach and supervise Governors and Regents in implementation.

For new permits that are exempted and may still be issued inside the Indicative Map areas, the Minister of Environment is instructed to reduce emissions of the business activities by issuing environmental licenses. It is assumed to mean that these licenses will restrict allowable GHG emissions.

The Ministry of Forestry is given primary responsibility for reviewing and updating the Indicative Map and reporting to the president at least once every six months, in cooperation with the Head of the National Spatial Planning Coordinating Agency, Head of the Coordinating Body for National Survey and Mapping, Governors, Regents, Mayors, and the Head of the REDD+ Task Force. The Head of the REDD+ Task Force is instructed to monitor implementation and submit a report to the president.

This updating process does not only have consequences on the physical delineation of primary forest and peatlands, it also moves the licensing authority on non-forested lands (other usage areas) to the Ministry of Forestry as stated in Section Four of the decree.

This decree does however involve many of the important ministries and agencies and specifies their role and the need to work together. This is an important step forward in managing lands and forests more efficiently and sustainably. This is also consistent with indicators of ‘good governance’.

Process: What processes will be put in place regarding reviewing permits, cooperation and coordination of government agencies, increasing transparency and participation, making maps and spatial data publicly available, and settling disputes

The decree includes some instructions to agencies regarding improving governance. For example:

The Minister of Forestry is instructed to: (1) improve policies on issuing permits on the use of timber in natural forest areas and (2) improve management of lahan kritis (“critical” or degraded forest) through ecosystem restoration concessions.

The Minister of the Environment is instructed to improve governance of business activities within the areas shown on the Indicative Map through environmental permits.

Multiple agencies are instructed to coordinate the map revision process and provide information to monitor and report to the President on a regular basis.

The Head of the National Spatial Planning Coordinating Agency is instructed to accelerate the consolidation of the Indicative Map into the spatial planning map revision as part of land use governance reform, in cooperation with other agencies. This could ensure that primary forest and peatland that is not already under some form of legal protection is appropriately zoned through the spatial planning process, with the status change lasting beyond the two-year moratorium period.

The decree does not make any specific provisions for reviewing or revoking permits, increasing transparency and participation, or making maps and spatial data publicly available.

The omission of an exemption for community forestry permits—when many exemptions were made including for industrial activities— is a major weakness in the decree.

Addressing Unanswered Questions

An effective moratorium would help to improve land use planning and permitting processes that contribute to Indonesia’s development goals and respect local rights, continuing beyond the two-year suspension period.

Important unanswered questions include:

- What specific areas are included in the moratorium and what data and methods were used to identify them? What are the extent, location, and status of existing and already exempted permits? How will this information be made publicly available?

- What instructions will be given to the Minister of Mines and Energy?

- How will provisions be made to allow legal community-based forest management during the two-year period, and to strengthen local management options in the future?

- How will government agencies interpret and by what process will they implement the instructions provided regarding ‘improving governance’?

- What additional actions will be taken regarding the governance of areas not identified on the Indicative Map?

The Indonesian government can begin to help answer some of these questions by ensuring that a digital version of the Indicative Map, source data layers, associated methods, and accurate information on the extent, location, and status of existing and already exempted permits, are made publicly available.

What are additional priorities for the two-year moratorium period?

In addition, as acknowledged by the government, achieving these goals will require taking many actions in the two-year moratorium period that are not addressed in the Presidential Decree. This includes putting in place REDD+ policies such as improved land use planning and permitting processes, reviewing or revoking illegal permits, encouraging expansion of agriculture and timber plantations onto degraded land instead of forested land (e.g. sustainable palm oil expansion on degraded land) and developing incentives for existing permits on forested lands to be swapped for permits on degraded lands (e.g. voluntary land swaps).

The main purpose of this decree, as identified in a previous article, is to create time for the government, business and civil society to develop and implement changes that will lead to more sustainable land management while stimulating economic growth, such as:

- Comprehensive, accurate, and regularly updated spatial data and maps on land cover and forest type, land use, land status, and land rights—including permits—made publicly available through easily accessible websites.

- Revised land use plans (zoning) such that appropriate natural forest and peatlands are classified for conservation or sustainable management and appropriate degraded lands are classified for agricultural or other uses, through a process that incorporates best practices in participatory spatial planning.

- Transparent and participatory processes for reviewing, revoking, reissuing, or relocating permits that are illegal or are in areas that are inappropriate for development, incorporating best practice stakeholder engagement and including the free prior and informed consent of relevant communities.

Whether this Presidential Decree contributes to achieving the goals of the Indonesia-Norway agreement on REDD+ is highly dependent on how remaining unanswered questions are addressed and what additional actions the Indonesian government takes—with the participation of industry and civil society—during the two-year period.