Less than 10% of tropical forests are ‘sustainably’ managed

More than 90 percent of tropical forests are managed poorly or not at all, says a new assessment by the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO).

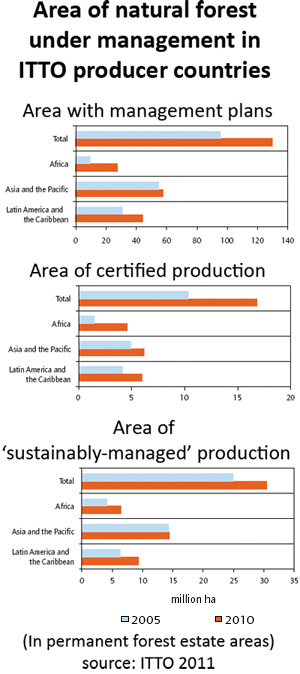

The report, Status of Tropical Forest Management 2011, finds that while forests continue to be degraded and destroyed at a rapid pace there are signs of hope. ITTO says the area of natural tropical forest under “sustainable management” in Africa, Asia-Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean increased by 47 percent from 36 million hectares (89 million acres) to 53 million hectares (134 million acres) between 2005 and 2010. Over the same time the extent of timber production under some form of management plan increased by about a third to 131 million hectares.

“We are of course happy to see the progress that has occurred in the last five years, but it still represents an incremental advance, and some countries are still lagging behind,” said Emmanuel Ze Meka, ITTO’s Executive Director, in a statement.

|

The report, which collected detailed country-by-country data on forest management in the world’s major tropical timber producing countries, finds the most rapid gains in Africa, where forest areas with management plans increased 180 percent from 10 million hectares to 28 million hectares between 2005 and 2010. Latin America and the Caribbean saw its forest area under management plans increase 43 percent, while Asia’s extent of forest management largely stagnated.

The report also reviews a number of the trends in forest management, including certification of timber products like that operated by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC); emerging payments for ecosystem services mechanisms like the much-hyped Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) program, which aims to pay tropical countries for protecting their forests; and new regulations for timber imports like the Lacey Act.

The report concludes that each of these trends on its own probably won’t be enough to ensure effective management of forests.

“We fully support the emergence of new markets for ‘green’ timber and the recent push to include forests in a climate change accord, but in many countries these developments alone may not be transformational,” Meka said. “Demand for certified wood is likely to affect only a small part of the tropical forest estate.”

Duncan Poore, an author of the report and former Director of the Nature Conservancy in the UK and former Director-General of the IUCN, said the REDD alone wouldn’t provide enough of a financial incentive to keep forests standing in some countries. Therefore, he says, the move to expand the program to include “sustainable forest management” was “essential.”

“With the economics of land-use in the tropics skewed away from maintaining forests for any purpose—either conservation or production—we need to ensure that we use all available tools that provide revenue for maintaining standing forests to compete with alternative land-uses such as agriculture and biofuels,” he said in a statement. “REDD has considerable promise but it’s essential that it evolves to recognize and support initiatives focusing on sustainable utilization of tropical forest resources, including sustainable timber production, as opposed to becoming primarily a fund to conserve forests.”

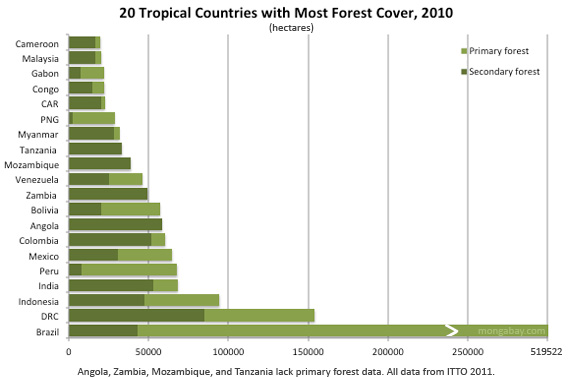

The inclusion of selective logging in REDD allows loggers to harvest virgin forests for timber. Accordingly, the report provides data on primary forest cover in many tropical countries. It also offers figures on deforestation rates since 2005, timber production, and allocation of forest lands as well as profiles for 33 tropical countries.

The report says resolving unclear land rights is critical to progress on forest management. Africa lags far behind other regions in sorting out land tenure; Latin America #8212; especially Brazil and Ecuador — has seen the most progress in addressing land title issues.

“Slowing or halting the loss or degradation of tropical forest will require disentangling the knot of tenure claims to many forested areas that is thwarting efforts to implement sustainable forestry,” said Meka. “Sustainable forest management is unlikely to succeed unless the forest has secure tenure that has been determined transparently on the basis of negotiation between claimants.”

The report notes that local communities need more resources to implement management programs, a position supported by Rights and Resources Initiative Coordinator Andy White, who was not involved in the publication.

“Today’s report shows that less than 10 percent of all forests are sustainably managed and that ITTO expects deforestation to continue,” said Andy White, Coordinator of the Rights and Resources Initiative, in a statement. “The report also shows that reforming tenure and supporting community forestry are needed to prevent the continued loss of tropical forests and the industrial clearing and logging that leads to deforestation, poverty, and human rights abuses.”

CITATION: Blaser, J., Sarre, A., Poore, D. & Johnson, S. (2011). Status of Tropical Forest Management 2011. ITTO Technical Series No 38. International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama, Japan.