Lesser flamingo (Phoenicopterus minor) with egg. Photo © Anup Shah.

Lesser flamingo (Phoenicopterus minor) with egg. Photo © Anup Shah.

It’s not easy to find a single word to describe witnessing hundreds of thousands of flamingos filling up a shallow lake in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa. ‘Spectacle’ comes to mind, but even this is not wholly accurate for the surreal pink crowd. However one describes it, this biological wonder may be under threat as Tanzania plans to mine in a flamingo breeding ground that is not only regionally important, but globally. Astoundingly, over half of the world’s lesser flamingos (between 65-75%) are born in a single lake in northern Tanzania: Lake Natron. This shallow salt lake provides optimal habitat for flamingos and their chicks as the caustic environment keeps mammal predators at bay. But conservationists worry that plans to mine soda ash—also known as sodium carbonate, which is used in making glass, chemicals, and detergents—would disrupt the sensitive birds’ breeding grounds, threatening the species and putting a damper on East Africa’s tourism industry.

Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete recently resurrected the plan to mine in Lake Natron after it was abandoned in 2008 due to concerns from Tanzania’s National Environmental Management Council (NEMC) that mining would impact the birds’ breeding success.

“There is no need for further delay,” Kikwete said, “because experience shows that the excavation can continue without any disturbance to the ecosystem there, environmental activists want people to believe that the move will wipe out the flamingo population, which is not true.”

But Tanzanian isn’t planning on simply re-considering the $450 million mine—which would be constructed by Indian company, Tata Chemicals—they want its approval ‘fast-tracked’. In fact, the East African reports that Tanzania’s Minister for Industry and Trade, Cyril Chami, has recently stated that even if a current Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) finds against construction of a soda ash factory, the government will build it anyway.

Mass breeding at Natronl

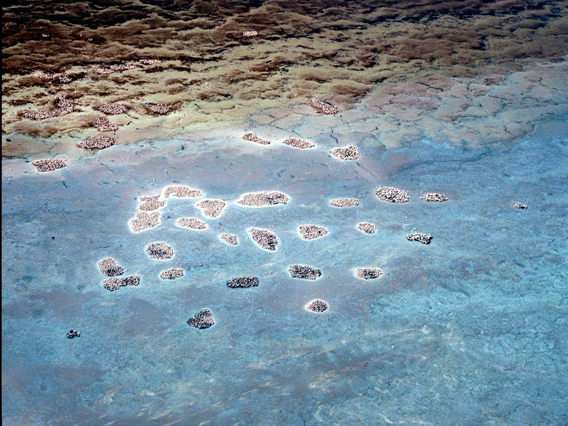

Aerial view of Lake Natron with flamingos (seen as tiny dots) nesting on islands. Photo courtesy of Neil Baker.

To protect the flamingos, Kikwete has promised the factory will not be built on the lake itself, but 70 kilometers away. Soda ash would then be moved from the lake to the factory via pipelines, which the president assures would save flamingos from disturbance. However, conservationists are skeptical.

“The disruption on the surface of the lake by workers and pipes will prevent most of the breeding and reduce the success rate,” Neil Baker told mongabay.com. Having lived in Tanzanian for 30 years, Baker is the author of Important Bird Areas in Tanzania.

According to Baker, the sensitive lesser flamingo “depends on successful large-scale breeding events at Lake Natron to augment the population,” making the lake the “only significant” breeding site for these birds in East Africa and the most important in the world. On average good breeding events happen every five years or so.

Matt Aeberhard, director of Disney Nature’s film The Crimson Wing: Mystery of the Flamingos which is set at Lake Natron, told mongabay.com that even when a year goes by without a big breeding event, Lake Natron still provides important habitat for “significant” small breeding events.

Although numbering around two million, the lesser flamingo has been classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List, because it has seen ‘moderately rapid reductions’ in its population.

“It is most probably already in decline due to large-scale die offs and a series of poor breeding seasons,” says Baker. “But, and this is important, we do not know as no one counts these birds on a regular basis. ”

And this is the crux of the problem for conservationists: researchers suspect mining activities would critically disrupt breeding, but lack the research necessary to know for certain. While the forthcoming Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) may shed some light on the issue, the government has already signaled the mine will go ahead no matter the study’s findings.

Water

What really keeps ornithologists up at night regarding mining at Lake Natron is water. Aeberhard says flamingos will not breed at Lake Natron if the natural water cycle is upset. The birds breed either in shallow waters during the dry season or following a heavy rain in the wet season. The level of water has to be balanced: too much and the mud flats on which the flamingos nest are flooded, too little and the surface become desiccated. Once fledged, chicks will perish if they don’t have quick access to water.

Lake Natron as viewed from satellites. Image by: NASA. |

“Any large scale mining at Natron that might disturb the natural hydrological balance at the lake is likely to cause issues, particularly if it involves extraction of large amounts of water from the lake,” explains Aeberhar, adding that “it could also be argued that mining might actually increase breeding opportunities too, because it is possible that mining could create greater amounts of wet soda area than what might occur naturally in any given year.”

Given the dearth of studies on Lake Nation, scientists simply don’t know how the birds will react.

“Clearly there can be no ‘wise use’ of a ‘resource’ without knowledge, and we still have no knowledge of Lake Natron and the flamingos from serious time based studies conducted by professional ornithologists and scientists at the lake over a number of years,” says Aeberhard.

One thing that is clear is that soda ash mining is incredibly water intensive. If the water needed to process the minerals is taken from the lake’s wetlands—and not shipped in—it could devastate the ecosystem.

However, President Kikwete, who has set a goal of nearly doubling Tanzania’s industrial sector by 2025, says it’s in the country’s best interests to mine the lake.

“What matters here is the application of sophisticated technology which is not harmful to flamingo’s breeding. At times I wonder whether those who are opposing this move are really patriotic, because it seems as if they are agents of some people we don’t know,” President Kikwete said, who commonly paints those who oppose his plans as unpatriotic or meddling foreigners.

Lake Magadi in Kenya

Kikwete argues that Tanzania may go ahead without fear at Lake Natron, because Kenya to the north is already mining soda ash at another shallow salt lake—Lake Magadi—that is still frequented by flamingos.

But there are significant differences between Magadi and Natron.

“There are no major rivers (so no mud) flowing in to Lake Magadi, the brine is of a higher quality than at Natron and easier to mine,” explains Baker. Sodium carbonate is also plentiful at Lake Magadi. “At current extraction rates there are still thousands of years of resource remaining.”

But, while flamingos can often be found feeding in Lake Magadi, they almost never breed there.

“Within human memory flamingoes have only bred once at Lake Magadi,” says Baker, “in early 1963 they were forced to abandon lake Natron due to flooding and in desperation moved north to Magadi. [The lake] is not isolated enough from mammalian predators and suffers from far too much human disturbance to be a suitable site for these flamingos.”

For flamingos Lake Natron is the breeding ground, while Magadi and a series of other lakes in the Great Rift Valley are used primarily for feeding. Disruptions at Magadi is not likely to decimate the flamingo population, whereas Lake Natron is another story.

At stake

Breeding group of lesser flamingos, known as a creche. Photo © Anup Shah.

“We cannot continue to mourn about our country being poor while our minerals are lying untapped,” Kikwete argues. The mine is seen as a way for Kikwete to make progress on promises of jobs and economic growth.

But conservationists argue that such mining should not be rushed and, if nothing else, more research is needed to shed light on concerns. Other economic development projects could also be explored.

“[It] surprises me that the Tanzanian government hasn’t acknowledged the potential for exploring bio-technology at the lake (unique salt loving bacteria etc.),” says Aeberhard. “Particularly when the potential for high-tech industry to eliminate poverty in a country might be considered greater than [mining].”

At stake here is more than just flamingos: tourism throughout East Africa would be injured if the bird vanishes; Tanzania’s international reputation threatens to take a hit, especially with Lake Natron being dubbed an International Ramsar Wetland; and mining could imperil a number of other bird populations that make the wetlands surrounding Lake Natron their home. In addition, there are the local people who have largely been left out of the debate.

“Obviously it is the Tanzanian government’s prerogative to decide on the fate of Lake Natron,” says Aeberhard, “[but] clearly a ‘fast track’ development of Lake Natron cannot be in the best interest of Tanzania, and it certainly cannot be in the best interest of the lake and the cultural traditions of its people (the Maasai of Natron) who will have this development forced upon them without having any say in its form or development.”

Mining at Lake Natron is only one issue that has both local and international conservationists concerned about recent Tanzanian policies. Retracting an application for UNESCO Heritage site status from the Eastern Arc Mountains and building a new port over a marine park at Mwambani Bay have also raised hackles. But the most controversial and most widely reported of them all is Tanzania’s plan to build a road through the northern Serengeti, which researchers say would in time cripple the world’s largest remaining land migration. The other concerns—including mining at Lake Natron—have largely gone under the radar due to the fight over the Serengeti.

Perhaps the Tanzanian government should be given the benefit of the doubt: maybe government officials are right in assuming that if all precautions are taken they can mine at Lake Natron without disturbing the flamingos. However, if they are wrong—and some say that scenario is more likely—then the surreal spectacle of hundreds of thousands of pink birds filling the lakes of the Great Rift Valley could for our great grand children seem as remote and lost as the idea of a million passenger pigeons blotting out the sun.

Trailer for The Crimson Wing: Mystery of the Flamingos

Related articles

(04/14/2011) What’s happening in Tanzania? This is a question making the rounds in conservation and environmental circles. Why is a nation that has so much invested in its wild lands and wild animals willing to pursue projects that appear destined not only to wreak havoc on the East African nation’s world-famous wildlife and ecosystems, but to cripple its economically-important tourism industry? The most well known example is the proposed road bisecting Serengeti National Park, which scientists, conservationists, the UN, and foreign governments alike have condemned. But there are other concerns among conservationists, including the fast-tracking of soda ash mining in East Africa’s most important breeding ground for millions of lesser flamingo, and the recent announcement to nullify an application for UNESCO Heritage Status for a portion of Tanzania’s Eastern Arc Mountains, a threatened forest rich in species found no-where else. According to President Jakaya Kikwete, Tanzania is simply trying to provide for its poorest citizens (such as communities near the Serengeti and the Eastern Arc Mountains) while pursuing western-style industrial development.

Conservation organizations ask Tanzania to reconsider UNESCO status for Eastern Arc Mountains

(05/02/2011) Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete has recently stated he would withdraw the application to list two Eastern Arc Mountains as UNESCO World Heritage sites:

Udzungwa and Uluguru Mountains. However, ten NGOS, both local and international, have asked the president to reconsider, according to The Citizen.

Serengeti road project opposed by ‘powerful’ tour company lobby

(03/16/2011) Government plans to build a road through Serengeti National Park came up against more opposition this week as the Tanzanian Association of Tour Operators (Tato) came out against the project, reports The Citizen. Tato, described as powerful local lobby group by the Tanzanian media, stated that the road would hurt tourism and urged the government to select a proposed alternative route that would by-pass the park. Tato’s opposition may signal a shift to more local criticism of the road as opposition against the project has come mostly from international environmentalists, scientists, and governments.