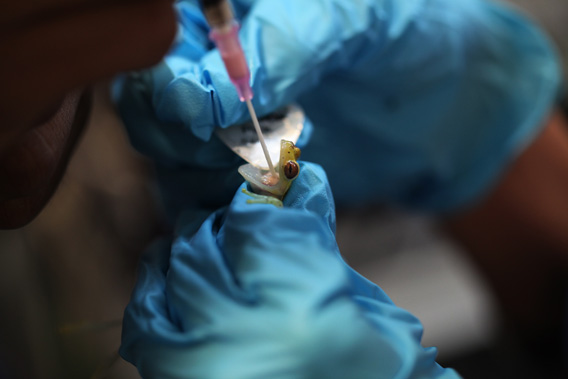

Hyloscirtus colymba tree frog being fed after being treated for Chytridiomycosis. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler at Summit Park.

In forests, ponds, swamps, and other ecosystems around the world, amphibians are dying at rates never before observed. The reasons are many: habitat destruction, pollution from pesticides, climate change, invasive species, and the emergence of a deadly and infectious fungal disease. More than 200 species have gone silent, while scientists estimate one third of the more than 6,500 known species are at risk of extinction. Species are disappearing even before they are described by scientists — a study published in Proceedings of the Nation Academy of Sciences last year found that 5 of the 30 species known to have gone extinct in Panama’s Omar Torrijos National Park since 1998 were unknown to science.

But the news gets worse. Chytridiomycosis — which is caused by a microscopic fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) that lives in water and soil — is spreading, metastasizing across Central and South America, Africa, and Australia. Amphibians are even experiencing rapid decline in habitats unmarred by the pathogen, pesticides, or direct human influence. Research in Costa Rica has recorded a 70 percent decline in amphibians over the past 35 years in pristine habitats, suggesting that climate shifts are taking a toll.

Atelopus certus. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler at Summit Park. |

Scientists now call the worldwide decline of amphibians one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group could follow.

In Panama, scientists are taking the threat to amphibians very seriously — chytrid recently “jumped” the Panama canal, moving West to East across the country toward Colombia. Conservationists have set up an an emergency conservation measure to capture wild frogs from infected areas and safeguard them in captivity until the disease is controlled or at least better understood. The frogs will be bred in captivity as an insurance policy against extinction.

Panamanian golden frog or (Atelopus zetecki) harlequin toad at the Bronx Zoo. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler  Unknown frog species being examined at the Summit Park facility of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. |

The initiative, known as the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, involves eight institutions: Africam Safari, ANAM (Panama’s environmental authority), Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Defenders of Wildlife, Houston Zoo, Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Summit Municipal Park in Panama, Zoo New England. The process is painstaking and expensive — once brought in from the wild each individual frog must be treated for chytrid, quarantined, and sometimes hand-fed for up to a month — but may be the only way to save some species from extinction. The project is also working to develop a cure for chytrid that could eventually allow extinct-in-the-wild amphibians to be reintroduced.

So far the project has established two facilities in Panama: one at the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center in western Panama and another at Summit Park near Gamboa in central Panama. Each has its own set of species targeted for rescue based on a prioritization system developed by the Amphibian Ark, a global initiative to reduce amphibian extinctions around the world.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is run by two biologists: Brian Gratwicke of Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Washington D.C. and Roberto Ibáñez of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. Both believe saving amphibians is important beyond protecting them for their own right: amphibians play an essential ecological role in food webs, help control pest populations, and even offer pharmacological benefits — several drugs have been derived from frog secretions.

Ahead of Save The Frogs Day on April 29, 2011, Gratwicke and Ibáñez highlighted the importance of amphibians and detailed their efforts to save them.

AN INTERVIEW WITH BRIAN GRATWICKE AND ROBERTO IBÁÑEZ

mongabay.com: What is your background and how did you get interested in amphibians?

Brian Gratwicke at Summit Municipal Park, in the Panama Amphibian Rescue And Conservation Project’s Amphibian Rescue Pod. Photo courtesy of Brian Gratwicke |

Brian Gratwicke: I am from Harare, Zimbabwe and first got interested in amphibians when as a child I tried going on expeditions to find giant African bullfrogs, so big they could eat rats! I never found any bullfrogs, despite assurances from herpetology professors and historical pioneer accounts of early settlers around Harare being kept awake at night by the incessant whooping of bullfrogs! I guess my first experience with amphibians was with a declining population.

Dr. Ibanez swabbing Atelopus limosus for Bd at Sierra Llorona. Photo courtesy of Brian Gratwicke |

Roberto Ibáñez: I am a Panamanian biologist, did my undergraduate studies at the Universidad de Panama. Obtained MS and PhD at the University of Connecticut, under the advice of the amphibian behavioral ecologist Kentwood Wells, and graduating with a PhD in Zoology. I got interested in amphibians while I was an undergraduate student in Panama. At that time, I was part of a student association that conducted field expeditions, and I my interest focused in knowing more about the diversity of amphibians. In those days, it was not easy to identify them, since there few identification keys and the literature about them was not easy to compile.

mongabay.com: What is your primary focus today?

Roberto Ibáñez: I am still interested in describing the diversity of Panamanian amphibians. However, I am also focused in the study of the effects of Bd on amphibian populations in Panama, and possible dispersal vectors and monitoring the spread of the Bd. In addition, I am taking actions for the conservation of the amphibians of Panama, being involved in the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project.

mongabay.com: Could you briefly describe the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project?

Red-eyed tree frogs seem to be less affected by the disease. Photo taken in Panama by Rhett A. Butler |

Brian Gratwicke: A deadly amphibian disease called chytridiomycosis or Bd has swept through much of central and south America, wiping out tropical mountain-dwelling frogs everywhere except for Eastern Panama. The project’s aim is to establish assurance populations of frogs that we think are likely to go extinct when this disease does hit them. Our primary aim is to build capacity, like facilities to house frogs and jobs for well-trained Panamanians to run the conservation program. We were fortunate to have willing partners Africam Safari, Panama’s Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Defenders of Wildlife, El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, Houston Zoo, Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Summit Municipal Park and Zoo New England who provided the resources to get this project off the ground. We are also working on developing a probiotics cure for chytridiomycosis so that one day we may be able to return frogs to the wild.

mongabay.com: Is Bd the most immediate threat to amphibians in Panama?

Roberto Ibáñez: Panama has a system of protected areas, where habitats are being preserved. In general terms, this system of parks and protected provides adequate habitat for many species of amphibians. The Bd does not recognize park boundaries, infecting and wiping out populations of a wide range of amphibian species. Therefore, I will consider the Bd to be the most immediate threat to amphibians in Panama.

mongabay.com: What are some of the other threats in Panama?

Roberto Ibáñez: Habitat destruction and stream pollution outside and, sometimes, inside protected areas.

mongabay.com: When you visit the field, how do you determine which species and individuals to collect?

Angie Estrada and Jorge Guerrel at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project  Blue form of the Dart Frog (Oophaga pumilio). Photos taken in Panama by Rhett A. Butler |

Brian Gratwicke: Unfortunately this is based on experience. For example in Panama the Western-most harlequin frogs (Atelopus chiriquiensis, varius and zeteki) have been wiped out by the disease. Right now Atelopus limosus from Central Panama is being wiped out and based on our observations, we don’t think there will be large populations of these frogs surviving in the wild beyond the end of this year. We think that more than 30 species of harlequin frogs are now extinct as a result of Bd so saving all the extant Atelopus species in Panama is our number 1 priority. Other species like cane toads and red-eye tree frogs seem to weather the epidemic without going extinct, so there is no need to create insurance populations of those species. Using this approach we assembled a group of experts and systematically evaluated every species in Panama prioritizing them according to methodology developed by Amphibian Ark, an organization dedicated to building global capacity to mitigate amphibian extinctions.

mongabay.com: If you are in a Bd-infected site do you collect all the amphibians or just the ones that meet your criteria?

Brian Gratwicke: We only collect the priority species. Out of 200 species in Panama 50 are considered priority species. Our project has come up with a strategic plan that aims to rescue the 20 most vulnerable species that we can still find in sufficient numbers to create an assurance colony. These 20 species will be looked after in our amphibian rescue center in Gamboa and at the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center that was started in 2005 by a team led by the Houston Zoo.

mongabay.com: What is the process for disinfecting a Bd-carrying frog?

Brian Gratwicke: Bd-infected frogs are treated in quarantine with an antifungal itraconazol bath for 10 minutes a day for 10 days.

mongabay.com: Where is the Bd-line currently in Panama?

Brian Gratwicke: It has spread beyond central Panama and is entering eastern Panama. We still believe that a few sites in the Darien region on the Colombian border are Bd-free, but the heavy rains this year have prevented several planned expeditions this year to verify this, so we can’t say for sure.

mongabay.com: Do scientists have any better idea of what is causing Bd to spread?

Atelopus certus babies.  Baby Atelopus certus. Photos taken in Panama by Rhett A. Butler |

Brian Gratwicke: We have a fairly good understanding of the Bd life-cycle. It is a fungus that infects frog skin and forms a flask-shaped sporangium that is filled with swimming spores. These spores are dispersed in water and may reinfect the host or swim off to find a new frog. Aquatic amphibians tend to be the most vulnerable to Bd. Anything that moves frogs around or moves their spores can potentially spread Bd. We have a clear idea of what the pathways might be but nobody has evaluated the direct effect of people spreading the pathogen in muddy boots or nets. Herpetologists now take special precautions to disinfect boots and equipment, but we are not the only people that like to hike up streams in muddy boots!

mongabay.com: Are there any efforts to educate tour operators and tourists about ways to reduce the risk of spreading Bd in forest areas?

Roberto Ibáñez: Most serious tour operators know about this amphibian crisis, as well as the Panamanian environmental authorities. Warnings have been posted in parks and private reserves. Some private reserve owners ask their visitors to disinfect their gear to reduce the risk of spreading the Bd. However, this is not a common practice.

mongabay.com: How many species are currently part of the project?

Craugastor species  Atelopus certus. Photos taken in Panama by Rhett A. Butler |

Brian Gratwicke: Our new facility in Gamboa currently has 4 priority species of frogs, 3 harlequin frogs and a treefrog. We also have 3 undescribed species that may become extinct in the wild before we even have a scientific name for them. The El Valle Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Center has over 60 species — some for educational purposes — but they have large holdings of at least 10 important conservation species.

mongabay.com: Has the project been able to breed all of the species collected to date?

Brian Gratwicke: We have managed to breed 2 harlequin frogs and the tree frog. This was no small feat because we knew virtually nothing about the basic life history of some of these species and we were only able to persuade them to breed through heroic efforts of our keepers who would spend countless hours observing animals, documenting their behavior and being attentive to their needs.

mongabay.com: Why is it important to save frogs?

Atelopus limosus.  Hyloscirtus colymba. Photos taken in Panama by Rhett A. Butler |

Brian Gratwicke: Frogs are the sound of the rainforest at night they are the bright colored living jewels that you find along mountain streams during the day. We should save frogs because they were here long before we were and their disappearance speaks volumes about how badly we have looked after our one and only planet. We must save frogs because it is our responsibility, and in doing so we may just save ourselves.

Roberto Ibáñez: Amphibians are an key component of the food webs, they feed mainly on insects and other invertebrates, and the same time being prey for a suite of other animals such as insects, spiders, snakes, birds and mammals. Species that have a tadpole stage play an important role in aquatic ecosystems. In such cases, is considered that losing an amphibian species is ecological equivalent to losing two species, because of their ecological role in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

Related articles

Save the Frogs Day focuses on banning Atrazine in US

![]()

(04/26/2011) This year’s Save the Frogs Day (Friday, April 29th) is focusing on a campaign to ban the herbicide Atrazine in the US with a rally at the steps of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Kerry Kriger, executive director of frog-focused NGO Save the Frogs! and creator of Save the Frogs Day, says that Atrazine is an important target in the attempt to save amphibians worldwide, which are currently facing extinction rates that are estimated at 200 times the average. “Atrazine weakens amphibians’ immune systems, and can cause hermaphroditism and complete sex reversal in male frogs at concentrations as low as 2.5 parts per billion,” Kriger told mongabay.com.

Worldwide search for ‘lost frogs’ ends with 4% success, but some surprises

(02/16/2011) Last August, a group of conservation agencies launched the Search for Lost Frogs, which employed 126 researchers to scour 21 countries for 100 amphibian species, some of which have not been seen for decades. After five months, expeditions found 4 amphibians out of the 100 targets, highlighting the likelihood that most of the remaining species are in fact extinct; however the global expedition also uncovered some happy surprises. Amphibians have been devastated over the last few decades; highly sensitive to environmental impacts, species have been hard hit by deforestation, habitat loss, pollution, agricultural chemicals, overexploitation for food, climate change, and a devastating fungal disease, chytridiomycosis. Researchers say that in the past 30 years, its likely 120 amphibians have been lost forever.

30 frog species, including 5 unknown to science, killed off by amphibian plague in Panama

(07/19/2010) With advanced genetic techniques, researchers have drawn a picture of just how devastating the currently extinction crisis for the world’s amphibians has become in a new study published in the Proceedings of the Nation Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Studying frog populations using DNA barcoding in Panama’s Omar Torrijos National Park located in El Copé researchers found that 25 known species and 5 unknown species have vanished since 1998. None have returned.

Save the frogs, save ourselves

(09/04/2009) Amphibians are going extinct around the globe. As a scientist specializing in frogs, I have watched dozens of species of these creatures die out. The extinction of frogs and salamanders might seem unimportant, but the reality couldn’t be farther from the truth. Indeed, from regulating their local ecosystems, to consuming and controlling the population of mosquitoes and other insects that spread disease, to potentially pointing the way to new drugs for fighting diseases such as cancer or HIV-AIDS, the fate of these creatures is inexorably linked to our own.

Salamander populations collapse in Central America

(02/09/2009) Salamanders in Central America — like frogs, toads, and other amphibians at sites around the world — are rapidly and mysteriously declining, report researchers writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Disturbingly, salamanders are disappearing from protected areas and otherwise pristine habitats.

Armageddon for amphibians? Frog-killing disease jumps Panama Canal

(10/12/2008) Chytridiomycosis — a fungal disease that is wiping out amphibians around the world — has jumped across the Panama Canal, report scientists writing in the journal EcoHealth. The news is a worrying development for Panama’s rich biodiversity of amphibians east of the canal.

Photos: Top 100 most threatened amphibians named

(01/21/2008) Due to numerous factors–including habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and chytrid fungus–amphibians are probably the most threatened taxon of species in the world. Dr Jonathan Baillie, head of the EDGE organization which has just established an amphibian program, stated that “tragically, amphibians tend to be the overlooked members of the animal kingdom, even though one in every three amphibian species is currently threatened with extinction, a far higher proportion than that of bird or mammal species.” To help save these species on the brink, EDGE, apart of the Zoological Society of London, has compiled a list of the hundred most threatened and evolutionary distinct amphibians.

Bad news for frogs; amphibian decline worse than feared

(04/16/2007) Chilling new evidence suggests amphibians may be in worse shape than previously thought due to climate change. Further, the findings indicate that the 70 percent decline in amphibians over the past 35 years may have been exceeded by a sharp fall in reptile populations, even in otherwise pristine Costa Rican habitats. Ominously, the new research warns that protected areas strategies for biodiversity conservation will not be enough to stave off extinction. Frogs and their relatives are in big trouble.