Forest elephant. Photo by: Carlton Ward Junior.

An interview with Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz and Stephen Blake.

Warning: graphic images below.

It seems difficult to imagine elephants delicately tending a garden, but these pachyderms may well be the world’s weightiest horticulturalist. Elephants both in Asia and Africa eat abundant amounts of fruit when available; seeds pass through their guts, and after expelled—sometimes tens of miles down the trail—sprouts a new plant if conditions are right. This process is known by ecologists as ‘seed dispersal’, and scientists have long studied the ‘gardening’ capacities of monkeys, birds, bats, and rodents. Recently, however, researchers have begun to document the seed dispersal capacity of the world’s largest land animal, the elephant, proving that this species may be among the world’s most important tropical gardeners.

“In our paper we show that African forest elephants are the ultimate seed dispersers—they disperse vast numbers of seeds of a high diversity of plants in a very effective way […] Asian and African savanna elephants also disperse many seeds […] but seem to be less frugivorous [i.e. fruit-eating],” Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, co-author of a recent paper on African and Asian elephant seed dispersal in Acta Oecologica, told mongabay.com in an interview.

Stephen Blake, the study’s other co-author, says that the behavior of different elephant species, in this context, has more to do with habitat than species’ preference.

These Myrianthus arboreus are typical fruits targeted by large mammals and elephants in the Congo. Photo by: J.P. Vandeweghe. |

“African savannah elephants don’t disperse many seeds usually, but stick them in the Kibale forest in Uganda where fruit is accessible, and they become formidable seed dispersers,” Blake explains, “no large-bodied generalist feeding mammal is going to refuse a good fruit feed if it is available.”

Blake and Campos-Arceiz highlight in their study some plant species likely depend entirely on elephants for their dispersal, much as some orchids depend wholly on a single insect pollinator for propagation.

“The best documented case is the relationship of Balanites wilsoniana and savanna elephants in Uganda. Several studies have found that elephants consume and disperse lots of Balanites seeds, that no other animal disperses these seeds,” explains Campos-Arceiz.

However, Blake adds that the “cumulative impact of elephant dispersal” is more important than their connection to one species: “a few trees declining because elephant disappear is of course detrimental, but Balanites going extinct will be unlikely to have massive impact on the forest ecosystem. However, elephants going extinct means that the competitive balance of many many species, arguably over 100 in central Africa will be tipped in favor of species poor abiotically [i.e. non-biologically, such as wind] dispersed species. That is the key point from an ecological perspective.”

The seed of Borassus flabelifer, retrieved from elephant dung. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

One of the reasons elephants are so important to a forest ecosystem is, unlike many other species, elephants are capable of spreading seeds far from the parent tree. According to the researchers, Asian elephants spread seeds from 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) to 6 kilometers (3.7 miles), while in the Congo, forest elephants are capable of spreading seeds as far as 57 kilometers (35.4 miles).

“These are truly unprecedented dispersal distances for large forest seeds—most animal dispersers in tropical forests will drop seeds just a few tens or hundreds of meters from the source,” explains Campos-Arceiz.

Despite their ecological important, elephants in Asia and Africa are threatened. While some populations of savannah elephants in Africa are stable, Blake says Africa’s forest elephants—the world’s biggest frugivores—are in “steep decline due to poaching “.

Asian elephants face pressures from poaching in addition to human-elephant conflict and habitat loss.

“Asian elephants are rapidly declining and now they exist mainly in small and fragmented populations. Asian elephants have lost most—probably over 95%—of their range in historical ranges. […] Nowadays, one out of three Asian elephants is a captive animal,” explains Campos-Arceiz, who says that priority in Asian elephant conservation is dealing with rising human-elephant conflict.

In central Africa, Blake says the economic, education, and social situation has become so poor that if forest elephants are to survive drastic measures may be needed.

Asian elephant bull in the water, Bundala National Park, Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

“I am afraid a very un-politically correct fortress mentality needs to be imposed inside national parks until there is a new world order for valuation of natural resources…there simply isn’t the financial incentive or other benefits to get local communities interested in conserving elephants […] but how to do this with ever decreasing funds and ever increasing external threats getting closer to park borders every day is the challenge,” Blake says,adding that “land use planning that respects the needs of wide ranging species like elephants, strong law enforcement, and socio-economic, political and environmental stability are among potential solutions, but Central Africa (just like the rest of the world for that matter) is a long way from these things.”

Blake believes that the plight of the seed-dispersing elephant is in some ways emblematic of the globe’s wider conservation, environmental, consumption and even philosophical problems.

“We need to generate some higher ideal in the general public beyond the next car and big house life goal…we need to make people think of the connection between their buying a cheap product and the reasons why it is cheap,” says Blake. “Elephants are simply one more natural resource that is being caught up in human greed on the one hand and human need on the other. We somehow need people to become reacquainted with nature, or they can have no clue as the interrelatedness of cause and effect. This philosophical change will be way too late for elephants if it ever comes, and with 9 billion people estimated to be here soon, the tsunami is just going to sweep over the last great wilderness areas and take their natural resources with it, elephants and all.”

And if Blake is right and elephants disappear for good from the forests they once dominated?

Over 250 elephant carcasses were found in the Mouadje Bai rainforest in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the late 1990s, killed as entire families for the ivory of the adults. Photo by: J.M. Fay. |

“Overall, we can expect a loss of biodiversity and a simplification of forest structure and function,” Campos-Arceiz explains succinctly.

And so, the gardener has abandoned their plot leaving it to an expanding monoculture of weeds.

In an April 2011 interview Stephen Blake and Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz discussed the importance of Asian and Africa elephants to tropical seed dispersal, the varied threats facing elephants, and ways to save the world’s greatest horticulturalists.

INTERVIEW WITH AHIMSA CAMPOS-ARCEIZ AND STEPHEN BLAKE

Mongabay: What are your backgrounds?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: I’m from Spain but moved to Asia almost one decade ago. I have been since then studying large Asian herbivores, mainly elephants in Sri Lanka but also Mongolian gazelles, Japanese sika deer, and Malayan tapirs. After many years based at the University of Tokyo, and a short period at the national University of Singapore, I’m now in Kuala Lumpur, working at the Malaysian campus of the University of Nottingham.

Stephen Blake: I am British. Began working in the Congo Basin in 1990 at a gorilla orphanage, then started with the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1993. Did a Masters (1993) and PhD (2002) at the University of Edinburgh: Phd on forest elephant ecology. Am now a researcher with the Mac Planck Institute for Ornithology, working on Galapagos tortoises.

ELEPHANTS: THE MEGAGARDENERS

Mongabay: Why are elephants important to the forests they inhabit?

Fruit of Dillenia indica, an elephant delicacy. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Elephants are important because they play unique functional roles in the forest they inhabit. All animals are involved to some extent in ecosystem processes but elephants, as the largest animals in the forest, do it in unique ways. Elephants alter the physical structure of vegetation when they feed, they mobilize large amounts of nutrients with their feces, they provide food and create habitats for a large number of vertebrates and invertebrates, and of course, disperse the seeds of many of the plants they consume, therefore, promoting forest maintenance and regeneration.

Stephen Blake: Remember too that at natural density elephants can make up the great majority of mammalian biomass in tropical forests. So elephants are using a large fraction of the energy flow through animals. Their body size means that they do things that other animals just don’t do—move seeds over larger distances than other dispersers, etc.

Mongabay: Which of the elephant species are the greatest seed dispersers?

Legume seedlings sprouting from elephant dung, Bago Yoma, Myanmar. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: In our review paper we show that African forest elephants are the ultimate seed dispersers—they disperse vast numbers of seeds of a high diversity of plants in a very effective way (e.g. over long distances and improving their germination capacity). Asian and African savanna elephants also disperse many seeds and can be extremely important, but seem to be less frugivorous (we also know less about of their role in seed dispersal).

Mongabay: Why do you think Asian elephants disperse less seeds?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: That somehow puzzles me. I think the main difference lies in Asian forests, rather than in the elephants. In Southeast Asia, forests are dominated by dipterocarps—wind-dispersed trees with complex supra-annual cycles of mast fruiting. Non-dipterocarp trees often follow these mast-fruiting cycles as well. For frugivores, this means that fruit is a less abundant and reliable food resource than in other tropical moist forests. This is probably one of the reasons why Asian elephants seem to be less frugivorous than their African forest relatives, in spite of otherwise many parallelisms in their ecology. In any case, Asian elephants are very fond of large fleshy fruits and it would be very interesting to study their importance as seed dispersers during mast-fruiting episodes.

Stephen Blake: Agreed: it is the composition and structure of the forest, not some intrinsic choice by the elephants. African savannah elephants don’t disperse many seeds usually, but stick them in the Kibale forest in Uganda where fruit is accessible, and they become formidable seed dispersers…no large-bodied generalist feeding mammal is going to refuse a good fruit feed if it is available.

Mongabay: Is there evidence of elephants as the sole seed dispersers for some species?

Old piles of elephant dung become fertile grounds for seed germination. Photo by: Stephen Blake. |

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Yes, there are quite a few examples of plants whose seeds are solely dispersed by elephants. The best documented case is the relationship of Balanites wilsoniana and savanna elephants in Uganda. Several studies have found that elephants consume and disperse lots of Balanites seeds, that no other animal disperses these seeds, that being consumed by elephants greatly enhances the capacity of Balanites seeds to germinate, and in places without elephants there is no recruitment of juvenile Balanites trees away from adult trees.

Steve Blake has also documented as many as 13 species that largely rely on forest elephants to disperse their seeds in Ndoki forest, Congo.

In Asia we have no well-documented case. I’m currently preparing studies in Sri Lanka and Malaysia looking at potentially obligate dispersal by Asian elephants. We definitely need more people studying the relationship between elephants and the so-called megafaunal-syndrome fruits (those supposedly adapted to dispersal by megafauna). And yes, this is a call to Asian students interested in the topic!

Stephen Blake: Humans have considerable overlap with the big seeded stuff; our estimate of 13 in Congo was probably too high, and definitely if humans are included which they need to be. The central point for me is not how many species elephants are sole dispersers of, but the cumulative impact of elephant dispersal…a few trees declining because elephant disappear is of course detrimental, but Balanites going extinct will be unlikely to have massive impact on the forest ecosystem. However, elephants going extinct means that the competitive balance of many many species, arguably over 100 in central Africa will be tipped in favor of species poor abiotically dispersed species. That is the key point from an ecological perspective.

Mongabay: How does elephant’s intelligence aid them in finding food and in turn dispersing seeds?

Seedling of Sandoricum koetjape, Taman Negara, Malaysia Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

Stephen Blake: How important intelligence is hard to say without specific studies, but it is likely to be high.

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: It must play an important role. Finding fruit in the forest is quite challenging because fruit is a very clumped resource—both in space and time—and the plants with large fruits dispersed by elephants often occur at very low densities. In our paper we speculate that elephants probably have cognitive maps that allow them to remember where and when fruits are likely to be available, very much in the same fashion as savanna elephants know where to find water during dry spells. Chimpanzees are known to use these cognitive maps in their search for fruit.

Besides individual memories, elephants have a ‘societal spatial memory’ in the form of permanent trails, carved in the forest by generations of elephants moving to and from dependable resources. As Steve described in a previous paper, these trails trap-line fruiting trees and other important resources. Of course, by moving along these trails elephants also disperse a higher number of seeds in their surroundings, in a self-reinforcing process of habitat ‘improvement’.

Mongabay: How far do elephants disperse seeds? Why does this matter?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Elephants regularly disperse large seeds over several kilometers. In my study with Asian elephants I found that in Sri Lanka and Myanmar they dispersed 57% of seeds more than 1 kilometers (0.62 miles) away from the mother plant, with maximum distances of up to approximately 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) (playing with unpublished data from a different Burmese population I found dispersal distances of over 20 kilometers (12.4 miles)!). But these distances look short compared with what Steve describes in Congo, where African forest elephants dispersed 82% of seeds farther than 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) and some seeds as far as 57 kilometers (35.4 miles)!! These are truly unprecedented distances for large forest seeds—most animal dispersers in tropical forests will drop seeds just a few tens or hundreds of meters from the source.

Dispersal distance is one of the main determinants of the spatial distribution of seeds, which has an important influence on tree distribution patterns and therefore forest structure. Trees dispersed over long distances by elephants have wide geographic distributions, low degree of spatial aggregation, and occur at low densities. Long-distance seed dispersal events also play a key role in process like plant migration (e.g. in response to climate change), connectivity of isolated populations (e.g. in forest fragmentation scenarios), and re-colonization of degraded habitats (e.g. after abandonment of agricultural fields).

Mongabay: If elephants are gone do other species make up for their absence in terms of seed dispersing?

Secondary roads, tertiary roads, and skidder trails (like the one above) open up every corner of the forest in the Congo, threatening elephants and over species. Photo by: D. Wilkie. |

Stephen Blake: The loss of elephants is the herald of mass crashes in populations of other large mammals usually to the bushmeat trade, so the species that could jump into fulfill some of the elephant role on competitive release—gorillas chimps, large duikers, etc, wont be there either. In the Congo basin, this is compounded by Ebola, for example, which is wiping out gorillas from vast areas of forest. So we should not see elephants disappearing as an isolated event, but as a more obvious signal of wider ecological collapse.

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Plants rarely put ‘all the eggs of their dispersal in a single basket’—they generally have multiple and complementary mechanisms to disperse. Most fleshy fruits are dispersed by a variety of animals, which continue to disperse seeds in the absence of elephants. Generally there is some level of functional redundancy.

In the case of elephants, however, because of their unique functional characteristics there is less redundancy and mechanisms to compensate their loss. Some plants with very large seeds might not find any other animal disperser (e.g. Balanites wilsoniana in Africa or Borassus flabelifer in Asia). And even if there are animals that still disperse the seeds (e.g. scatter-hoarding rodents), the spatial patterns of dispersal change drastically, resulting in a very different ecological trajectory for the plant—e.g. species distribution range constrain, the spatial distribution of adults becomes more clumped, genetic structure increases locally, and ultimately many populations disappear.

Mongabay: How do you believe forests will change if elephant populations plunge or even go extinct locally?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Elephants have already disappeared over large areas of Africa and Asia, and from the Americas, so forest must have changed already. The main changes that we can expect are: plants with very large fruits and seeds (specialized in dispersal by megafauna) will fail to recruit and will become increasingly rare, until they eventually disappear; plants that are dispersed by elephants and other animals will see their patterns of dispersal modified, which will result in range reductions, increased spatial aggregation and genetic structure of populations, and higher risk of local disappearance; and plants that are not dispersed by large animals (especially those dispersed by abiotic [i.e. non-biologic, such as wind] factors) will gain a competitive advantage and become more dominant.

Overall, we can expect a loss of biodiversity and a simplification of forest structure and function.

CONSERVATION OF ELEPHANTS

Bull Asian elephant crossing a road close to Bundala National Park, Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz.

Mongabay: What is the difference between African forest elephants and savannah elephants? A recent study found that the African forest elephant was a distinct species. Do you believe this?

Stephen Blake: It is all still up in the air. A new paper just came out in PLOS Biology talking about “deep speciation among African elephants”, but it is all still a matter of opinion. Right now the African elephant specialist group still has 2 subspecies for African elephants.

Mongabay: If they are separate species what are the conservation implications?

Stephen Blake: As far as conservation implications, I am not sure it will make much difference in practical terms to have two separate species defined, though in the short to medium term it might make things even more difficult for forest elephants. CITES would immediately open the trade in the savannah species, which would increase the price of ivory in the world market and demand would rise. Rising demand and rising prices will make it even more profitable for black marketers to operate, which they will be able to do in the absence of effective law enforcement. The key is law enforcement, and because law enforcement in exporting and importing countries is often weak due to corruption and lack of funding and expertise, illegal ivory from the Congo Basin would be easier to shift into the world market. Now the traders say this is not the case, and that the legal market would be well controlled, but their evidence for this is scant.

Mongabay: What is the status of the African forest elephant populations?

This elephant in the Gamba oil field in Gabon has a snare biting into its left front leg. Snaring elephants is an effective means of killing in parts of central Africa. Photo by: Stephen Blake. |

Stephen Blake: The status of African elephant populations is highly varied between regions and taxa. Southern African elephants are stable or increasing generally, eastern African elephants ditto, central African forest and savannah elephants are in steep decline due to poaching and habitat loss. West African elephants seem to be relatively stable, but they are highly fragmented and found mostly in tiny populations, so the outlook for them is pretty poor. I think the southern African nations are complacent in their outlook of stability for their elephants. As middle class Chinese get richer and as Asia buys up Africa, we are going to see dramatic rises in ivory demand and price on the black market whatever happens to the legal trade. Couple this to political influence and corruption, and we are set to see elephants being hit hard in what are currently secure areas.

Mongabay: And what is the status of the Asian elephant populations?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: The situation of elephant populations in Asia is complex. Something easy to understand is that Asian elephants are rapidly declining and now they exist mainly in small and fragmented populations. Asian elephants have lost most—probably over 95%—of their range in historical times. This decline is still going on, with an estimated loss of around 80% of the range during the 20th century alone (!!). Nowadays, one out of three Asian elephants is a captive animal. And countries like Myanmar and Thailand might currently have more captive than wild elephants. So things don’t look good for Asian elephants.

Moreover, Asian elephants inhabit some the most populous countries in the world. Current local densities of Asian elephants in areas of Sri Lanka, India, and others are actually unsustainably high, because elephants living close to people inevitably resort to crop raiding and other forms of human-elephant conflict (HEC), which leads to retaliatory killing of elephants and the eventual elimination of these populations. In many areas Asian elephants are perceived as ‘overabundant agricultural pests’. Since elephants are long-living animals, we need to keep in mind that demographic effects appear long after environmental changes. Many Asian elephant populations that are now under intense HEC can be considered living-dead populations, with little long-term hope.

Mongabay: What conservation measures would you suggest for the Asian elephant?

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz checks a dead elephant, victim of human-elephant conflict in Southeast Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. |

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: In my opinion, the priority in Asia is learning to deal with human-elephant conflict. Up to now, HEC has always led to the local extirpation of elephants. As human populations expand there are less and less elephants that can live without interacting with people. We need to learn how to minimize the damage caused by elephants to local communities (through the understanding of the ecological and behavioral factors that lead to crop raiding) and how to increase the level of tolerance in people (living with elephants involves risks and consequences that cannot be ignored altogether). It is not going to be easy, but understanding the real impact of HEC on people’s livelihood and the sociocultural factors behind their perceptions and attitudes will be very important.

Mongabay: And what conservation measures would you suggest for the African forest elephant?

Stephen Blake: It is always about the same old thing…protection, wildlife management, education and outreach, work with community leaders to generate local buy in, and good natural resource management. Unfortunately the same old thing has failed and is failing because the resources just are not there. You know, central Africa is getting deeper into environmental and social problems every day: in the Congo we are seeing a generation coming to maturity who have had little education, and who have poor employment prospects. The big economic drivers, the Chinese, for example, are bringing in their own workers for logging and mining operations, at a time when the world’s desire for both international aid and philanthropy is rapidly diminishing.

So, working with the private sector is critical for developing a conservation landscape. Conservation investment needs to be linked to market forces for the sale of timber and minerals and oil. Bad environmental companies need to be penalized and “good” ones rewarded, but as we see every day, this is tough in practice. Have you seen the latest from BP?—their growth strategy is to remain unchanged following a bad spell after the Gulf disaster…there is always a market out there whether the operator is “good” or “bad” , and as global demand for resources escalates, particularly in Asian markets, it will be the price of the raw materials in the mass market not high-end green luxury-end market that counts…and low prices cannot be maintained if companies have to invest in good road planning, anti-poaching, and other environmentally and socially friendly practices.

Monyaka is a typical pygmy elephant poacher. Monyaka has killed well over 100 elephants, worth thousands of dollars in ivory. Mostly he was paid in either alcohol or cigarettes for his ivory. Photo by: Stephen Blake. |

I am afraid a very un-politically correct fortress mentality needs to be imposed inside national parks until there is a new world order for valuation of natural resources…there simply isn’t the financial incentive or other benefits to get local communities interested in conserving elephants except in a few highly subsidized areas, like villages whose populations are employed by the parks, but how to do this with ever decreasing funds and ever increasing external threats getting closer to park borders every day is the challenge. Land use planning that respects the needs of wide ranging species like elephants, strong law enforcement, and socio-economic, political and environmental stability are among potential solutions, but Central Africa (just like the rest of the world for that matter) is a long way from these things.

Mongabay: Where would you like to see research of elephants as megagardeners go next?

Stephen Blake: I think research must get very applied at this point. We need to look at things like carbon benefits of elephant dispersal…what is the net carbon gain for having elephants plant hard wood tree species of high wood density compared to wild dispersed species of low wood density? There is some interesting work beginning in this regard. Keeping a mammal-rich forest intact may provide very tangible carbon benefits, and since the only currency the world currently understands is money based on an oil based economy, we have to jump on the bandwagon, imperfect though it is.

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: We need a lot of baseline data. We need Asian students to study frugivory and seed dispersal by elephants in different environments, especially in tropical moist forests of South and Southeast Asia. We need to identify the dispersal mechanisms of many megafaunal-syndrome plants. And we also need to identify the changes that are taking place in forest structure after the loss of elephants and other large herbivores (e.g. forest rhinos).

Mongabay: What can the general public do to help?

A victim of the illegal killing of elephants. This infant’s mother was killed while raiding crops in an oil concession. Photo by: S. Deem. |

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: This is a difficult one. I would really encourage people living within elephant ranges to understand that human-elephant conflict is part of the deal and that it can’t be solved unless all the elephants are removed.

For those that don’t live with elephants I would encourage them to make financial contributions to conservation and research organizations because funds are a serious limitation to conduct elephant conservation projects; become educated consumers and reduce the purchase of products that harm elephant habitats (e.g. products containing unsustainably-produced palm oil, or wood from illegal logging); and be aware that certain elephant shows and activities in Asia depend on the unsustainable supply of elephants from wild populations, and should not be encouraged.

Stephen Blake: Beyond all of the above we need to generate some higher ideal in the general public beyond the next car and big house life goal…we need to make people think of the connection between their buying a cheap product and the reasons why it is cheap. Why is “Wholefoods” food expensive? Because it comes from ecologically managed sources. All food should cost that much in the first world, and we should eat less and consume less as a society. But that is not economic reality. Why are US cars so huge? Because the price of fuel is so cheap. What are the consequences of cheap fuel and massive cars? How many Americans and Europeans jump in their big SUV from their big house and give one second of thought to the consequences of what they are doing, and whether it is a tad wasteful. Elephants are simply one more natural resource that is being caught up in human greed on the one hand and human need on the other. We somehow need people to become reacquainted with nature, or they can have no clue as the interrelatedness of cause and effect. This philosophical change will be way too late for elephants if it ever comes, and with 9 billion people estimated to be here soon, the tsunami is just going to sweep over the last great wilderness areas and take their natural resources with it, elephants and all.

CITATION: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz and Stephen Blake. Megagardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in seed dispersal. Acta Oecologica. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2011.01.014.

A captive Asian elephant cow, Millennium Elephant Foundation, Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz.

House attacked by elephant to consume stored rice, Southeast Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz.

Curious young male forest elephant re-establishing a presence in a successful conservation area, Nouabale-Ndoki, northern Congo. Photo by: Stephen Blake.

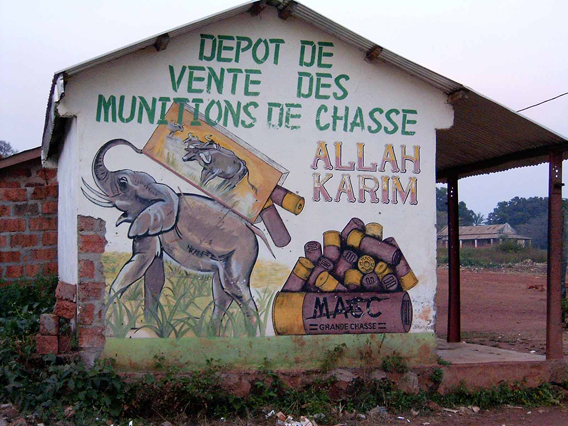

Shop in the main street in Bangassou in the Central Africa Republic advertising for elephant hunting. This shop is 200 yards from the wildlife protection office. Photo by: L. Williamson.

Almost non-existent law enforcement means that elephant meat is offered for sale openly in village and town markets in Central African Republic. Photo by: L. Williamson.

Ivory market at Lagos airport in Nigeria. Photo by: D. Stiles.

Ivory carving has a long history in Europe as well as in Asia. Photo by: D. Stiles.

Two Asian elephant bulls playing in Udawalawe National Park, Sri Lanka. Photo by: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz.

Related articles

Vanishing forest elephants are the Congo’s greatest cultivators

(04/09/2009) A new study finds that forest elephants may be responsible for planting more trees in the Congo than any other species or ghenus. Conducting a thorough survey of seed dispersal by forest elephants, Dr. Stephen Blake, formerly of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and now of the Mac Planck Institute for Ornithology, and his team found that forest elephants consume more than 96 species of plant seeds and can carry the seeds as far as 57 kilometers (35 miles) from their parent tree. Forest elephants are a subspecies of the more-widely known African elephant of the continent’s great savannas, differing in many ways from their savanna-relations, including in their diet.

(04/09/2009) A new study finds that forest elephants may be responsible for planting more trees in the Congo than any other species or ghenus. Conducting a thorough survey of seed dispersal by forest elephants, Dr. Stephen Blake, formerly of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and now of the Mac Planck Institute for Ornithology, and his team found that forest elephants consume more than 96 species of plant seeds and can carry the seeds as far as 57 kilometers (35 miles) from their parent tree. Forest elephants are a subspecies of the more-widely known African elephant of the continent’s great savannas, differing in many ways from their savanna-relations, including in their diet.

Frogs species discovered living in elephant dung

(06/10/2009) Three different species of frogs have been discovered living in the dung of the Asian elephant in southeastern Sri Lanka. The discovery—the first time anyone has recorded frogs living in elephant droppings—has widespread conservation implications both for frogs and Asian elephants, which are in decline. “I found the frogs fortuitously during a field study about seed dispersal by elephants,” Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, a research fellow from the University of Tokyo, told Monagaby.com.

(06/10/2009) Three different species of frogs have been discovered living in the dung of the Asian elephant in southeastern Sri Lanka. The discovery—the first time anyone has recorded frogs living in elephant droppings—has widespread conservation implications both for frogs and Asian elephants, which are in decline. “I found the frogs fortuitously during a field study about seed dispersal by elephants,” Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, a research fellow from the University of Tokyo, told Monagaby.com.

Africa gains new elephant species

(01/19/2011) DNA evidence has shown that the forest elephant-Africa’s smaller, shyer pachyderm-is indeed a separate species from the much more well-known savanna elephant. While scientists have long debated the status of the forest elephant (should it be considered a separate population, a subspecies, or a unique species?) a new study in the open-access journal PLoS Biology finds that genetically the forest elephant is unarguably a new species. If conservation authorities accept the new study, it will change elephant conservation efforts throughout Africa.

Bushmeat hunting alters forest structure in Africa

(11/04/2010) According to the first study of its kind in Africa, bushmeat hunting impacts African rainforests by wiping-out large mammals and birds—such as forest elephants, primates, and hornbills—that are critical for dispersing certain tree species. The study, published in Biotropica, found that heavy bushmeat hunting in the Central African Republic changes the structure of forest species by favoring small-seeded trees over large-seeded, leading to lower tree diversity of trees that have big seeds.

Elephant tromping benefits frogs and lizards

(10/25/2010) While elephants may appear destructive when they pull down trees, tear up grasses or stir up soils, their impacts actually make space for the little guys: frogs and reptiles. The BBC reports that a new study in African Journal of Ecology finds that African bush elephants (Loxodonta Africana), facilitate herpetofauna (i.e. amphibians and reptiles) biodiversity when they act as ecosystem engineers.

One man’s mission to save Cambodia’s elephants

(05/17/2010) Since winning the prestigious 2010 Goldman Environmental Prize in Asia, Tuy Sereivathana has visited the US and Britain, even shaking hands with US President Barack Obama, yet in his home country of Cambodia he remains simply ‘Uncle Elephant’. A lifelong advocate for elephants in the Southeast Asian country, Sereivathana’s work has allowed villagers and elephants to live side-by-side. Working with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) he has successfully brought elephant-killing in Cambodia to an end. As if this were not enough, Sereivathana has helped curb the destruction of forests in his native country and built four schools for children who didn’t previously have formal education opportunities.

A nation of tragedies: the unseen elephant wars of Chad

(05/12/2010) Stephanie Vergniault, head of SOS Elephants in Chad, says she has seen more beheaded corpses of elephants in her life than living animals. In the central African nation, against the backdrop of a vast human tragedy—poverty, hunger, violence, and hundreds of thousands of refugees—elephants are quietly vanishing at an astounding rate. One-by-one they fall to well-organized, well-funded, and heavily-armed poaching militias. Soon Stephanie Vergniault believes there may be no elephants left. A lawyer, screenwriter, and conservationist, Vergniault is a true Renaissance-woman. She first came to Chad to work with the government on electoral assistance, but in 2009 after seeing the dire situation of the nation’s elephants she created SOS Elephants, an organization determined to save these animals from local extinction.

Protected areas vital for saving elephants, chimps, and gorillas in the Congo

(05/10/2010) In a landscape-wide study in the Congo, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) found that core protected areas and strong anti-poaching efforts are necessary to maintain viable populations of forest elephants, western lowland gorillas, and chimpanzees—all of which are threatened with extinction.

CEO sentenced for smuggling elephant ivory into US

(03/14/2011) A judge sentenced Pascal Vieillard, CEO of A-440 Pianos Inc., to 3 years probation for illegally smuggling elephant ivory into the US, while the Georgia-based company has been fined $17,500. Vieillard had earlier pleaded guilty to importing pianos with ivory parts.

Chinese citizen caught smuggling ivory from the Republic of Congo

(01/24/2011) A Chinese national was caught attempting to smuggle 22 pounds (10 kilos) of ivory out of the Republic of Congo on Saturday, according to the AFP. Officials confiscated five elephant tusks, 80 ivory chopsticks, 3 ivory carvings, and a number of smaller ivory-made items.

95% of Liberia’s elephants killed by poachers

(01/24/2011) Since the 1980s, Liberia has lost 19,000 elephants to illegal poaching, according to Patrick Omondi of the Kenya Wildlife Service speaking in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. The poaching of Liberia’s elephants has cut the population by 95% leaving only 1,000 elephants remaining.

(03/07/2010) There are few areas of research in tropical biology more exciting and more important than seed dispersal. Seed dispersal—the process by which seeds are spread from parent trees to new sprouting ground—underpins the ecology of forests worldwide. In temperate forests, seeds are often spread by wind and water, though sometimes by animals such as squirrels and birds. But in the tropics the emphasis is far heavier on the latter, as Dr. Pierre-Michel Forget explains to mongabay.com. “[In rainforests] a majority of plants, trees, lianas, epiphytes, and herbs, are dispersed by fruit-eating animals. […] As seed size varies from tiny seeds less than one millimetres to several centimetres in length or diameter, then, a variety of animals is required to disperse such a continuum and variety of seed size, the smaller being transported by ants and dung beetles, the larger swallowed by cassowary, tapir and elephant, for instance.”

Hunting across Southeast Asia weakens forests’ survival, An interview with Richard Corlett

(11/08/2009) A large flying fox eats a fruit ingesting its seeds. Flying over the tropical forests it eventually deposits the seeds at the base of another tree far from the first. One of these seeds takes root, sprouts, and in thirty years time a new tree waits for another flying fox to spread its speed. In the Southeast Asian tropics an astounding 80 percent of seeds are spread not by wind, but by animals: birds, bats, rodents, even elephants. But in a region where animals of all shapes and sizes are being wiped out by uncontrolled hunting and poaching—what will the forests of the future look like? This is the question that has long occupied Richard Corlett, professor of biological science at the National University of Singapore.

Elephants on the rampage in India: 500 homes destroyed, seven people dead

(09/08/2009) A herd of 12-13 elephants has caused havoc in the Kandhamal district of India, reports the BBC. The elephants have completely destroyed 500 homes, left seven dead, and sent another 500 people to camps for shelter.

Elephants populations in the Congo drop 80 percent in fifty years

(03/11/2009) According to the conservation organization Wildlife Direct , Wildlife Direct a recent survey of elephants in the Democratic Republic of Congo reveals that populations have dropped 80 percent in fifty years. The survey was conducted by John Hart using forest inventories, aerial surveys, and interview with local peoples.

High ivory prices in Vietnam drive killing of elephants in Laos, Cambodia

(02/19/2009) Indochina’s remaining elephants are at risk from surging ivory prices in Vietnam, according to a new report from the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC.

Wildlife trade creating “empty forest syndrome” across the globe

(01/19/2009) For many endangered species it is not the lack of suitable habitat that has imperiled them, but hunting. In a talk at a Smithsonian Symposium on tropical forests, Elizabeth Bennett of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) outlined the perils for many species of the booming and illegal wildlife trade. She described pristine forests, which although providing perfect habitat for species, stood empty and quiet, drained by hunting for bushmeat, traditional medicine, the pet trade, and trophies.

Forest elephants learn to avoid roads, behavior may lead to population decline

(10/27/2008) Forest elephants in the Congo Basin have developed a new behavior: they are avoiding roads at all costs. A study published in PLoS One concludes that the behavior, which includes an unwillingness to cross roads, is further endangering the rare animals which are already threatened by poaching, development, and habitat loss. By avoiding roads, the elephants are increasingly confining themselves to smaller areas lacking enough habitat and resources.