New monitoring system uses Google Earth to protect endangered archeological sites

A new alert system uses Google Earth and other satellite-based tools to protect cultural heritage sites from fire, looting, encroachment, destructive tourism, and other threats, says the Global Heritage Fund, the group that launched the initiative.

The platform, dubbed the Global Heritage Network (GHN – ghn.globalheritagefund.org), relies on high resolution satellite imagery and detailed maps of 500 key archeological and cultural heritage sites in developing countries around the world. Threats are reported by people in the field, including local communities, researchers, authorities, and volunteers.

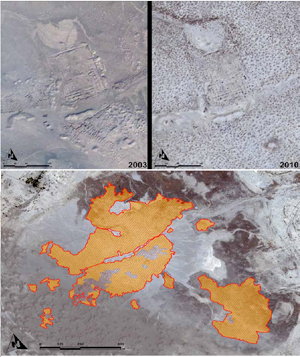

Umma, Iraq – Massive Looting of Sumerian Cities 2003-2010. Outlined and cross-hatched area is Total Area Looted as of 2010 since the Iraq war began in March, 2003. (DigitalGlobe and GHF) |

“GHN serves as an early warning system for our irreplaceable global heritage sites on the brink of being lost,” said Jeff Morgan, Executive Director of GHF, in a statement. “GHN expands our global network to engage a broader group of site conservation leaders, archaeologists, local communities, government officials, donors, and volunteers to save our global heritage for future generations.”

“With major threats such as the armed conflict endangering nearby Preah Vihear Temple on the contested Thai-Cambodian border, an early warning system for heritage sites is clearly needed to focus national and world attention and generate rapid responses to loss and destruction of global heritage.”

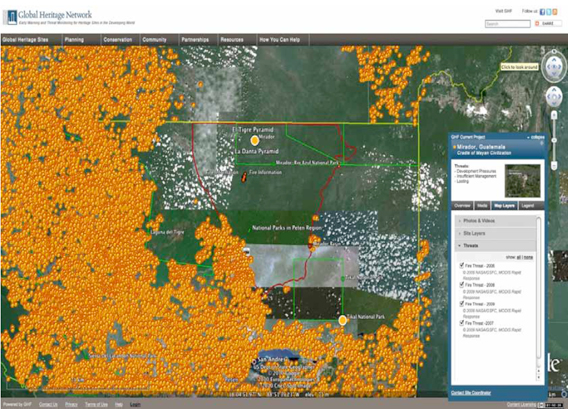

GHN uses scientific mapping from Esri and satellite imagery from DigitalGlobe to populate a geospatial database displayed on Google Earth. Information on threats is drawn from a variety of sources, including social networks, news reports, and, in the case of Mirador, Guatemala, where forest fires put ancient Mayan temples at risk, even NASA fire data. Threats are communicated via social media and other channels to authorities and the public.

Working with NASA and the University of Maryland, GHN has daily data feeds of fires threatening Mirador, a cultural and natural heritage site in Guatemala. Whenever a fire is detected near the basin, GHN receives an alert with the fire’s location, which can be sent to local authorities. By tracking

fires with daily MODIS images such as this one, GHN has mounted a campaign to preserve the forest. (Image: University of Maryland and GHF).

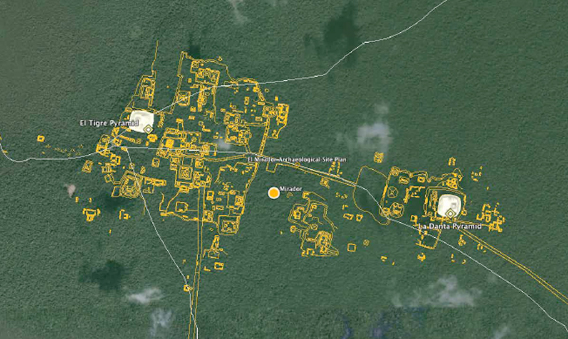

The site of El Mirador and the La Danta Pyramid, likely the largest man-made

pyramid in the world by volume. 3D models have been developed in GHN showing the

massive scale of these monuments. (DigitalGlobe and FARES)

But beyond providing threat monitoring capabilities, the Global Heritage Fund says GHN will help build local capacity and expertise in protecting cultural heritage sites in some of the world’s poorest countries.

“GHN enables our conservation team to work together with international experts and local community leaders to conserve sites like Banteay Chhmar, Cambodia’s leading nomination for UNESCO World Heritage designation,” said John Sanday, Director of the Banteay Chhmar project. “Our Khmer conservation team can now work closely with international experts around the world to monitor threats, propose innovative solutions and collaborate daily to save one of Southeast Asia’s most significant heritage sites.”

Global Heritage Fund says GHN will make it easier for developing countries to protect cultural heritage sites, which have potential to generate substantial revenue from tourism and other businesses — up to $100 billion a year by 2025 for the 500 sites in GHN, according to a 2010 Global Heritage Fund report.

Global Heritage Network.