Illegal logging on the edge of Gunung Palung National Park in West Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. This timber is being used to construct structures to attract swiftlets for the production of bird-nest soup, a delicacy in China. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011.

Over the past twenty years Indonesia lost more than 24 million hectares of forest, an area larger than the U.K. Much of the deforestation was driven by logging for overseas markets. According to the World Bank, a substantial proportion of this logging was illegal.

While deforestation rates have dipped since the late 1990s, illegal logging remains a problem in Indonesia. In fact it is seen as one of the biggest challenges for Indonesia in meeting the greenhouse gas reductions targets pledged by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono: in 2009 the Indonesian President pledged to unilaterally cut the country’s emissions 26 percent from a projected 2020 baseline.

Deforestation outside West Kalimantan’s Gunung Palung National Park. This forest was logged for timber, then burned. It will be planted with rubber. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011. |

Curtailing illegal logging may seem relatively simple: hire more forestry police to conduct more patrols, strengthen fines, prosecute cases, and implement better tracking systems for legitimate timber. But at the root of the problem of illegal logging is something bigger: Indonesia’s land policy. The bulk of Indonesia’s forest is owned by the state, which historically has doled out large concessions — often tens of thousands of hectares in extent — to logging companies. Local communities mostly lose out, leaving some to seek opportunities from illicit timber harvesting. Without clear ownership rights to land, communities have little incentive to reject illegal logging or manage forests for the long-term. The model — which has contributed to the abandonment of traditional land stewardship in many areas — has driven large-scale devastation of Indonesia’s rich forest ecosystems.

Can the tide be turned? There are signs it can. Indonesia is beginning to see a shift back toward traditional models of forest management in some areas. Where it is happening, forests are recovering. For example “people’s forests” in Java are, for the first time in generations, regrowing. Given a stake in forest ownership, communities in Java have an interest in reforestation for timber production and other benefits afforded by forests.

Telapak, a membership organization with offices on several Indonesian islands, understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the “new” forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

Telapak’s Ambrosius “Ruwi” Ruwindrijarto. Photo courtesy of Telapak/the Skoll Foundation |

Telapak’s interest in community logging emerged out of its advocacy and campaigning work against illegal logging. After a series of high profile campaigns — including one which resulted in co-founder Ambrosius Ruwindrijarto (“Ruwi”) being kidnapped and tortured by thugs hired by a local timber baron — Telapak decided it need to not just highlight environmental problems, but promote solutions.

Telapak has since expanded its goals to include securing and protecting local community ownership and management rights of forests. The broader scope is inherently more complex than advocacy work. Telapak must now work to build technical capacity on the ground, push legal reform, delve into politics, and build business models that sustain and nurture community forest management. The path promises to be a challenging one, but Telapak is growing: its members now manage more than 200,000 hectares of forest land across Java, Lombok, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua. It is also working in areas outside the forest sector, including fisheries, the ornamental fish trade, and mass media. All the while, Telapak continues its campaigning efforts, including a recent exposé on illegal logging and palm oil plantation development in Indonesian New Guinea: Papua and West Papua.

In a series of conversations with mongabay.com’s Rhett Butler, Ruwi discussed the evolution of Telapak and what is needed to protect and sustainably steward Indonesia’s natural resources.

AN INTERVIEW WITH TELAPAK PRESIDENT AMBROSIUS RUWINDRIJARTO

mongabay.com: What is your background and what led you to start Telapak?

Telapak’s Ambrosius “Ruwi” Ruwindrijarto. Photo courtesy of the Samdhana Institute |

Ruwi: I was active in the student nature club of Bogor Agricultural University, IPB. This is probably the biggest motivation for me, together with five other friends, to start Telapak in 1996. Telapak arose out of our collective hobby of enjoying nature and our desire to keep our friendship after graduation from the university.

mongabay.com: Did Telapak begin as an investigative activist group?

Ruwi: Telapak started as a foundation, co-founded by 6 friends from the same student nature club, Lawalata-IPB. It was supposed to be an activist group focused on nature study and outdoor activity — a place where friends could live off activities they enjoyed as students nature club, like mountaineering, climbing, jungle trekking, wildlife observation. On the second year of its inception, Telapak started to work specifically on forest investigation and campaigns. One of its first projects was creating a network and campaigning on logging concessions (HPH) in Indonesia, supported by USAID-funded BSP Kemala. Telapak’s network of forest investigators was then focused on investigating illegal logging, working with London-based Environmental Investigation Agency.

mongabay.com: Your commitment to forests was really put to the test in a 1999 incident near Tanjung Puting. Can you tell us about what happened?

Oil palm plantations in and around Tanjung Puting National Park in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, satellite image courtesy of Google Earth. |

Ruwi: I and my EIA colleague, Faith Doherty, confronted Tanjung Lingga Group, which was the master of illegal logging in Tanjung Puting National Park and many other areas in Kalimantan. The company hired thugs to take us from the hotel to the company office where we were then assaulted and held for many hours. The company controlled the whole town so they then turned us to the police, in this case the Criminal Investigation Division, thinking that that special division within the local police will follow whatever the company wants them to do to us. But this criminal investigation division turned out to be protecting us.

For the next three days there was a tug of war between this division and other police officers there, the military, and the company thugs. We were held in the division office because the office was surrounded by the mob, which was paid by the company. Eventually we were able to leave the office and flew back to Jakarta. This was after many negotiations by, and much pressure from, many people in Jakarta, as high as the Minister for Environment and the British Ambassador. Even the President Gus Dur was notified and made public remarks about the kidnap and torture.

mongabay.com: Were the perpetrators ever punished?

Ruwi: Sugianto who was the point man in the company, which owned by Abdul Rasjid, was sentenced very lightly by the local court. He got a few months’ probation sentence. Abdul Rasjid was never judicially processed. Sugianto is currently the elected Chief of District of Kotawaringin Barat. His victory in the election was disputed by a competitor due to “money politics” and the national Judicial Court cancelled Sugianto’s election. But Sugianto fought back and now the case is not yet settled. It is very likely he will get the position anyway.

mongabay.com: But the incident didn’t stop Telapak from doing investigations.

Ruwi: Yes. Telapak used the incident as a momentum to bring the campaign to even wider audience. The incident also provided an opportunity for Telapak to expose forest crimes in its whole range of complexity, including weak governance, corruption, and violence.

mongabay.com: What are some of your most recent investigative findings?

Ruwi: Recently Telapak is focusing its investigation into forest crimes in Papua. This includes illegal conversion of forests into oil palm plantations, smuggling of timber logs directly out of Papua to other countries, and bad governance in regards to forestry and land use planning.

Community forestry

mongabay.com: Why did you establish the community forestry arm of Telapak?

Illegal logging in West Kalimantan’s Gunung Palung National Park. Hardwoods are being trafficked by a timber barons in the town of Ketapang. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011. |

Ruwi: By 2006 we concluded that we needed to contribute to solving the other side of the problem: forestry and deforestation. While we have always been very strong in investigation, campaigning, and advocacy we felt that we need to also promote counter-argument or solution, which in this case is a new forestry paradigm of community-based and sustainable forestry. We call it community logging as this directly confronts the current approach which consists of the state claiming ownership of forest and handing it over to industrial logging concessions or turning it into plantation or mining areas. That year we launched Telapak campaign: “from illegal logging to community logging”. We want to argue that to address illegal and destructive logging in a level playing field we need to create and support sustainable community-based logging in which timber, whether you like it or not, is the main product of the forest. After all, it is timber that created all the problems in the first place. It is the product sought by those logging concessionaires, illegal loggers, and even plantation developers. It is common knowledge in Indonesia that oil palm plantation projects are often just a cover to get the license needed to clear cut a forest and harvest timber.

In pushing through with the new campaign Telapak relied on both practical experience from a successful community forestry of the Cooperative Hutan Jaya Lestari in Southeast Sulawesi and a few others, and a growing body of knowledge and discourse on community forestry that has long been practiced in Indonesia. Social forestry or community-based forestry has been supported for many decades in Indonesia by NGOs, donor communities, and even government agencies.

mongabay.com: How does the model work?

Ruwi: As we want to mainstream community logging as the new forest management regime in Indonesia, we are trying to simplify the model into the following phases:

Image courtesy of Telapak |

1. Securing and or protecting local community or indigenous people’s ownership or management rights of forest.

2. Social investment to organize the people into cooperative or other institutions that will own and or manage the forest, based on strong awareness and local capacity.

3. Technical investment in the form of participatory mapping and forest inventory, developing forest management plan, and other legal and capacity building needs of the community.

4. Business investment, which is based on a concept of local community as the owner of the capital asset, forest and its ecological-social-cultural features.

mongabay.com: Are communities pleased with the opportunity to earn legitimate income instead of relying on illegal logging?

Ruwi: Yes. And it’s not just better and legal income, but the non-monetary benefit too, like better social standing, self-esteem, good citizenship, and of course environmental benefits like ecosystem services: protection of watersheds, storage of carbon, preservation of biodiversity, and more.

mongabay.com: Do big logging companies see Telapak as a competitive threat yet?

Ruwi: Not yet. We are still struggling with the scale of our forestry and business turn over which is still very small compared to the big logging companies in Indonesia. But they do watch out right now and some have even started to follow the initiative.

mongabay.com: Have you found success in winning a premium for your wood products?

Ruwi: Yes. Although the volume is very limited right now.

mongabay.com: What are some of Telapak’s other activities?

Rainforest in West Kalimantan’s Gunung Palung National Park. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011. |

Ruwi: Telapak’s other activities include: developing community fishery models that are just and sustainable. The prototype is a environmentally-friendly ornamental fishery in Bali (which is the first of its kind in Indonesia) and fisher-based coral cultivation. This community fishery tries to mix conservation and economic improvement: the conservation effort in the area is financed by sustainable fishery Telapak developed together with fishermen organizations to export ornamental fish and cultured corals.

Another activity is water management, where Telapak works with NGO partners in several provinces to develop and implement negotiated approaches to mater resource management, including reconciling upstream and downstream interest, better understanding river issues, and public awareness on water issues. This sector for Telapak is still in development and Telapak has not yet created a model that can be used further for replication and scale-up.

Telapak also works through its business arms, including investment in media companies, organic commodities, herbs production, and several retail businesses.

Illegal logging in Gunung Palung National Park in West Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. This timber is being used to construct structures to attract swiftlets for the production of bird-nest soup, a delicacy in China, while precious hardwoods like meranti are being harvested for export to China. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011.

Indonesia

mongabay.com: Is the Norway-Indonesia partnership having any impact in Indonesia yet? Are companies realizing that this is now real since money is on the table?

Tree nursery for reforestation. Image courtesy of Telapak |

Ruwi: I don’t know about this. If any, the impact of the Norway-Indonesia has not felt in everyday life.

mongabay.com: In your opinion, what is most needed to make REDD a success in Indonesia? (e.g. what are the biggest challenges and best approaches?)

Ruwi: In my opinion what is most needed is just like the steps I mentioned above on community logging:

1. Secure and protected land/forest tenure

2. Strong community organization, social investment

3. Technical investment at various level related to REDD, starting with on the ground forest management practices.

4. Sound and just financial and market mechanism that follows the 1,2,3 above, and good governance of forest and everything else.

mongabay.com: Can a properly-designed REDD still appease the traditional power brokers like the bupati?

Ruwi: I don’t think so without addressing the whole historical and governance problems.

mongabay.com: If the U.S. were to decide to support REDD in Indonesia, what strategies would you suggest it take? Where should it invest?

Ruwi and Silverius Oscar Unggul (“Onte”) were presented with a Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship at the Skoll World Forum in 2010 for their work with Telapak. Left to right: Paul Hawken, Skoll Foundation CEO Sally Osberg, Onte, Ruwi, and Jeff Skoll.

|

Ruwi: I’ll stick to the steps I described above. The U.S. and others should invest on the underlying causes of deforestation and creating a new regime of forest management, like a community-based and sustainable forestry for example.

mongabay.com: Telapak is a bit unusual in Indonesia in that it is active across most of the archipelago. What does you see as the best way to strengthen civil society within Indonesia?

Ruwi: I think civil society needs to find strength, significance, and sustainability by becoming part of communities. In Telapak we say: living off the same forests and seas of indigenous peoples, farmers, and fishermen.

mongabay.com: Do you believe Indonesians are becoming more or less interested in environmental issues?

Ruwi: I believe that Indonesians are becoming more interested in environmental issues.

mongabay.com: What can people abroad do to help your efforts?

Ruwi: In general, what people abroad can do to help our effort is by thinking, doing, and consuming differently. Just like we are introducing and creating new ways of managing forest, producing and distributing commodities people abroad needs to contribute too by changing their mode of living and investing.

Ruwi’s presentation, in Indonesian, begins at 20:20.

Related articles

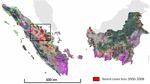

Indonesian Borneo and Sumatra lose 9% of forest cover in 8 years

(02/25/2011) Kalimantan and Sumatra lost 5.4 million hectares, or 9.2 percent, of their forest cover between 2000/2001 and 2007/2008, reveals a new satellite-based assessment of Indonesian forest cover. The research, led by Mark Broich of South Dakota State University, found that more than 20 percent of forest clearing occurred in areas where conversion was either restricted or prohibited, indicating that during the period, the Indonesian government failed to enforce its forestry laws.

Does chopping down rainforests for pulp and paper help alleviate poverty in Indonesia?

(01/13/2011) Over the past several years, Asia Pulp & Paper has engaged in a marketing campaign to represent its operations in Sumatra as socially and environmentally sustainable. APP and its agents maintain that industrial pulp and paper production — as practiced in Sumatra — does not result in deforestation, is carbon neutral, helps protect wildlife, and alleviates poverty. While a series of analyses and reports have shown most of these assertions to be false, the final claim has largely not been contested. But is conversion of lowland rainforests for pulp and paper really in Indonesia’s best economic interest?

Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work?

(12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources.

Violence a part of the illegal timber trade, says kidnapped activist

(07/07/2010) The European parliament made a historical move today when it voted overwhelmingly to ban illegal timber from its markets. For activists worldwide the ban on illegal timber in the EU is a reason to celebrate, but for one activist, Faith Doherty of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), the move has special resonance. In early 2000, Doherty and an Indonesian colleague were kidnapped, beaten, and threatened with a gun by illegal loggers in Indonesian Borneo.