Papua New Guinea, as viewed from Google Earth, covers the eastern half of the island of New Guinea, as well as other Pacific Islands.

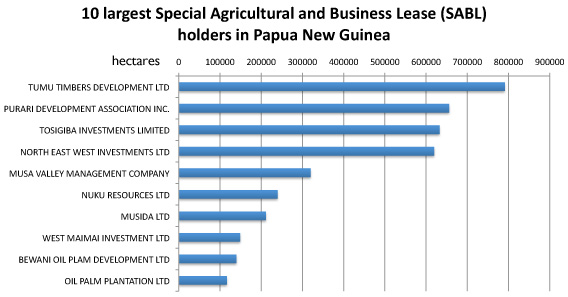

During a meeting in March 2011 twenty-six experts—from biologists to social scientists to NGO staff—crafted a statement calling on the Papua New Guinea government to stop granting Special Agricultural and Business Leases. According to the group, these leases, or SABLs as they are known, circumvent Papua New Guinea’s strong community land rights laws and imperil some of the world’s most intact rainforests. To date 5.6 million hectares (13.8 million acres) of forest have been leased under SABLs, an area larger than all of Costa Rica.

“Papua New Guinea is among the most biologically and culturally diverse nations on Earth. [The country’s] remarkable diversity of cultural groups rely intimately on their traditional lands and forests in order to meet their needs for farming plots, forest goods, wild game, traditional and religious sites, and many other goods and services,” reads the statement, dubbed the Cairns Declaration.

However, according to the declaration all of this is threatened by the Papua New Guinea government using SABLs to grant large sections of land without going through the proper channels. Already 2 million (nearly 5 million acres) hectares of the leased land has been slated for clearing by the government’s aptly named Forest Clearing Authorities.

Daniel Ase, Executive Director of the Papua New Guinea NGO, Center for Environmental Law and Community Rights (CELCOR), who participated in the meeting, told mongabay.com that this was “massive land grabbing […] basically for large scale industrial logging,” adding that “most of these areas are located in areas of high biodiversity in the country.”

Chart by mongabay.com.

The SABLs undercut indigenous communities by handing land over to largely foreign and multinational big corporations for leases that last 99 years, severing indigenous people from their land for generations. Last year alone, 2.6 million hectares (6.4 million acres) were granted under SABLs. Local communities have often not consented to the deals and in some cases weren’t even notified.

“Virtually all of Papua New Guinea is owned by one communal group or another, and at least in theory these groups have to approve any development on their land. This is one of the key reasons for the SABLs—it’s a way for the government to carve off large chunks of land for major logging and other developments, and to greatly diminish the role of local communities,” explains William Laurance, a leading conservation biologist with James Cook University, to mongabay.com.

According to Laurance, the revenue made from these deals is not aiding poverty alleviation efforts in Papua New Guinea, but instead the profits are “mostly ending up in the hands of foreign corporations and political elites in Papua New Guinea.”

Tribesman in Indonesian New Guinea. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

“For instance, local communities in Papua New Guinea are capturing only around $10 per cubic meter of kwila, one of their most valuable timbers, whereas the same raw timber fetches around $250 per cubic meter on delivery to China,” explains Laurance, adding that, “many of the major socioeconomic indicators for Papua New Guinea have fallen in the past decade, indicating a decline in living standards even as the country is experiencing a huge resource boom.”

While this may seem contrary to expectations, it is a pattern that has been repeated in many poor countries with great wealth in natural resources. Known to economists as the ‘resource curse’, such nations see their natural resources exploited while receiving little to no economic gain, instead promised funds are lost to bad business deals, corrupt politicians, or what have been described as ‘predatory’ foreign corporations.

The Cairns Declaration makes a similar point: “SABLs are a clear effort to circumvent prevailing efforts to reform the forestry industry in Papua New Guinea, which has long been plagued by allegations of mismanagement and corruption.”

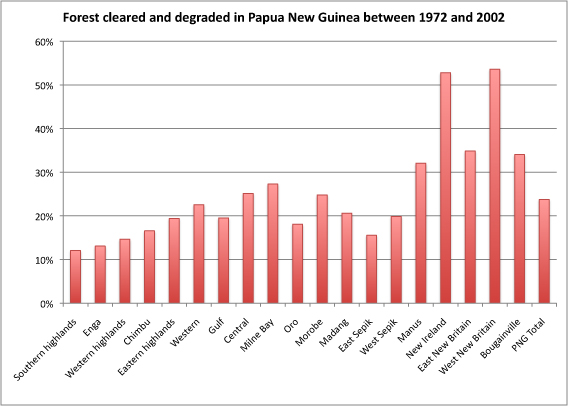

Unlike Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea had long been thought to have avoided massive deforestation, thereby retaining one of the last great rainforests outside of the Congo and the Amazon. However, a 2009 study found that between 1972-2002, nearly a quarter of the country’s forests were lost or degraded by logging.

“Forests in Papua New Guinea are being logged repeatedly and wastefully with little regard for the environmental consequences and with at least the passive complicity of government authorities,” Dr. Phil Shearman, director of the University of Papua New Guinea’s Remote Sensing Centre and lead author of the study, said at the time.

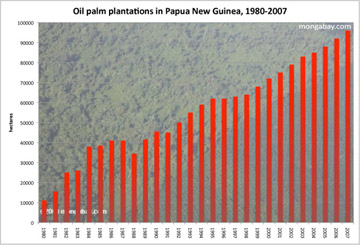

While logging for timber is the primary cause of forest loss in Papua New Guinea, the palm oil industry is on the rise. Palm oil has become targeted by environmentalists for being, at least in part, responsible for the environmental crises facing Malaysia and Indonesia.

Extent of oil palm plantations in Papua New Guinea from 1980-2007. Data courtesy of FAO. Click to enlarge. |

It doesn’t have to continue this way, says Laurance. Papua New Guinea could make in-roads against poverty while sustainably managing its forests.

“First, the country needs to develop a much greater domestic wood-processing industry. That way they can capture much more profit and employment from the exploitation of their forests. Right now Papua New Guinea has one of the lowest rates of wood processing of any country in the world. Second, the forests of Papua New Guinea are being seriously overharvested. They’ll soon exhaust their timber supplies if things keep going as they are now. So, they need to curtail harvests sharply and focus on developing a timber industry that’s oriented toward more value-adding, rather than letting somebody else make the profit.”

The Cairns Declaration urges the government to place a moratorium on granting new SABLs and handing out approvals to clear forests. An independent review should then be conducted on the legality of the leases.

Laurance says people can “write to Papua New Guinea’s National Executive Council (nec_secretary@pmnec.gov.pg), which includes the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, and express your serious concerns about the rampant increase in SABLs and their social and environmental costs. You could also send a brief letter to the editor of the Post-Courier Newspaper (postcourier@spp.com.pg),” adding that “these things unquestionably help.”

Related articles

Stopping export logging, oil palm expansion in PNG in 2012 would cost $1.8b, says economist

(03/07/2011) Stopping logging for timber export and conversion of forest for oil palm plantations would cost Papua New Guinea roughly $2.8 billion dollars from 2012 to 2025, but would significantly reduce the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to a new analysis published by an economist from the University of Queensland.

Biodiversity and slash-and-burn agriculture in Papua New Guinea

(12/20/2010) As pressures increase on the rich forests of Papua New Guinea, how will biodiversity fare? A new study in mongabay.com’s Tropical Conservation Science attempts to answer this question by looking at how bird species are impacted by slash-and-burn agriculture. While locals have been practicing such agriculture for 5,000 years, rising populations and societal changes are expected to increase the pressure of slash-and-burn agriculture on forests and the species that live there.

Foreign corporations devastating Papua New Guinea rainforests

(10/21/2010) A letter in Nature from seven top scientists warns that Papua New Guinea’s accessible forest will be lost or heavily logged in just ten to twenty years if swift action isn’t taken. A potent mix of poor governance, corruption, and corporate disregard is leading to the rapid loss of Papua New Guinea’s much-heralded rainforests, home to a vast array of species found no-where else in the world. “Papua New Guinea has some of the world’s most biologically and culturally rich forests, and they’re vanishing before our eyes,” author William Laurance of James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, said in a statement.

Papua New Guinea strips communal land rights protections, opening door to big business

(06/30/2010) On May 28th the parliament in Papua New Guinea passed a sweeping amendment that protects resource corporations from any litigation related to environmental destruction, labor laws, and landowner abuse. All issues related to the environment would now be decided by the government with no possibility of later lawsuits. Uniquely in the world, over 90 percent of land in Papua New Guinea is owned by clan or communally, not be the government. However this new amendment drastically undercuts Papua New Guinea’s landowners from taking legislative action before or after environmental damage is done. Essentially it places all environmental safeguards with the Environment and Conservation Minister.

(06/02/2010) Radical, controversial, ahead-of-his-time, brilliant, or extremist: call Dr. Glen Barry, the head of Ecological Internet, what you will, but there is no question that his environmental advocacy group has achieved major successes in the past years, even if many of these are below the radar of big conservation groups and mainstream media. “We tend to be a little different than many organizations in that we do take a deep ecology, or biocentric approach,” Barry says of the organization he heads. “[Ecological Internet] is very, very concerned about the state of the planet. It is my analysis that we have passed the carrying capacity of the Earth, that in several matters we have crossed different ecosystem tipping points or are near doing so. And we really act with more urgency, and more ecological science, than I think the average campaign organization.”

Cargill sells palm oil business in Papua New Guinea

(02/26/2010) Cargill will sell off its palm oil holdings in Papua New Guinea (PNG) to focus on operations in Indonesia, reports the Star Tribune. The $175 million sale involves 62,000 ha of oil palm across three plantations and several mills.

Asia’s biggest logging company accused of bribery, violence in Papua New Guinea

(02/08/2010) A local organization in Papua New Guinea, known as Asples Madang, is fighting against one of the region’s biggest industrial loggers, Rimbunan Hijau (RH) chaired by billionare Tiong Hiew King. Aspeles Madang has accused Malaysian company, RH, of acquiring land illegally and of using brute force and bribery in its dealing with locals.

Palm oil developers in Papua New Guinea accused of deception in dealing with communities

(09/25/2009) Papua New Guinea, the independent eastern half of the world’s second largest island (New Guinea), houses one of the planet’s last frontier forests. These forests support a wealth of plants and animals as well as the Earth’s most diverse assemblage of cultures—some 830 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea (PNG), representing more than 12 percent of the world’s 6,900. But PNG’s forests are fast-changing. Between 1972 and 2002 PNG lost more than 5 million hectares of forest, trailing only Brazil and Indonesia among tropical countries. Forest loss has been primarily a consequence of industrial logging and subsistence agriculture, but large-scale agroindustry—especially development of oil palm plantations—has emerged as an important new driver of land use change. Dozens of international companies have set up operations in the country over the past decade, including Cargill, an agribusiness giant based in Minneapolis. While Cargill says it is committed to sustainable and responsible palm oil production across its three plantations in PNG, the firm has been targeted by local and international NGOs, which claim it has polluted rivers and deceived local communities into signing agreements they do not understand. Some landowners say they are receiving few of the benefits oil palm promised to deliver, while losing their independence—they are now reliant on an export-oriented crop they can’t eat. Opposition to further oil palm expansion is now growing, especially in Oro Provice, where Cargill’s plantations are based.