Tigress photo captured at Nagarahole National park by camera trap. Copyright: K Ullas Karanth/WCS.

An interview with Krithi Karanth, a part of our Interviews with Young Scientists series.

Krithi Karanth grew up amid India’s great mammals—literally. Daughter of conservationist and scientist Dr. Ullas Karanth, she tells mongabay.com that she saw her first wild tigers and leopard at the age of two. Yet, the India Krithi Karanth grew up in may be gone in a century, according to a massive new study by Karanth which looked at the likelihood of extinction for 25 of India’s mammals, including well-known favorites like Bengal tigers and Asian elephants, along with lesser known mammals (at least outside of India) such as the nilgai and the gaur. The study found that given habitat loss over the past century, extinction stalked seven of India’s mammals especially: Asiatic lions, Bengal tigers, wild dogs (also known as dholes), swamp deer, wild buffalo, Nilgiri Tahr, and the gaur. However, increasing support of protected areas and innovative conservation programs outside of parks would be key to saving India’s wildlife in the 21st Century.

“The idea for this [study] came up as a result of discussions with my father Dr. Ullas Karanth. We were aware that many large mammals occurred very widely across India just 100 years ago. We were interested in comparing current and past distributions of species and factors that promote species persistence,” Karnath said.

In order to foretell the future, Karanth looked to the past to see how mammal ranges and populations have changed over the last century. Meticulous record-keeping by the British allowed Karanth to reconstruct the wild India of the past.

Krithi Karanth. |

“I was aware that the British had kept detailed records of their field visits and hunting expeditions particularly for large mammals. I began to compile these records from over 50 museums, hunting travelogues, taxidermy firms, journals [Journal of Bombay Natural History and Indian Forester…] I ended up a database with over 30,000 records for mammals alone,” she says.

A century of habitat loss and fragmentation, as well as poaching, hunting, and the wildlife trade have pushed India’s great mammals to the edge. Her results found that some species are facing almost inevitable extinction. The Asiatic lion and the swamp deer have disappeared from 90% of their historic range in the last 100 years. For others the future may not be so bleak.

“I am cautiously optimistic that tigers will continue to persist in the wild particularly in southern India where parks are well relatively protected. India has over 40% of the world’s tigers and is perhaps the most important tiger range country. There is a lot of political will to conserve this species and these efforts are being renewed once again,” she says.

Muntjac or Barking Deer. Nagarahole National Park. Copyright: Eleanor Briggs. |

Of course, the future is not yet decided and even India’s most threatened mammals could be saved. Karanth says that protected areas need to be strengthened, cultural tolerance for wildlife encouraged, and people impacted by human-wildlife conflict should be compensated.

Still, in a rapidly developing nation of “1.2 billion people using 97% of land area”, as Karanth says, India will never be as wild as it once was.

“The declines of species were so dramatic, widespread and so recent. I wish I could have seen what the country was like in 1800s with all this wildlife,” Karanth says.

In a February 2011 interview Krithi Karanth discussed the fate of 25 of India’s charismatic mammals, how her findings have been covered in India, and ways to save India’s wildlife for future generations.

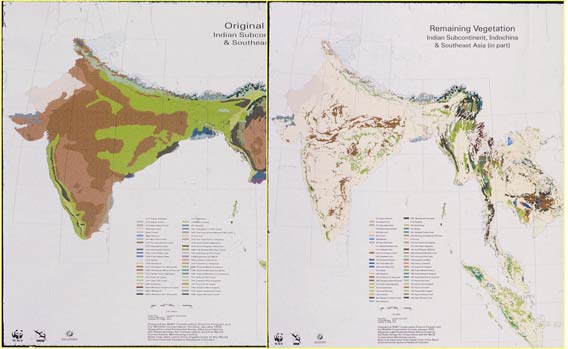

India’s original forest cover on the left. Today’s forest cover on the right. Click to enlarge.

INTERVIEW WITH KRITHI KARANTH

Mongabay: What is your background?

Krithi Karanth: I was born and raised in India. As a child I spent a lot of time with my father Dr. Ullas Karanth visiting several parks and watching wildlife with him. I saw my first wild tiger and leopard when I was 2 years old. I got to see him track tigers that he had collared in Nagarahole National Park in the 1990s. I moved to the US in 1997 for my Bachelors at University of Florida (UF), followed by masters at Yale, PhD at Duke and post doc at Columbia. I was very fortunate to have been mentored by several wonderful professors at all of these places.

Mongabay: Having studied geography as an undergraduate, what led you to pursue your studies in environmental science both at Yale and Duke?

Sloth Bear. Photo taken at Tadoba-Andheri Tiger reserve. Copyright: Harshawardhan |

Krithi Karanth: At UF I discovered my passion for Environmental Science and particularly designing inter-disciplinary projects. I pursued research as an undergrad under Dr. Mike Binford. Our research examined correlations between economic and environmental variables responsible for land-cover and land-use change in Thailand. This project allowed me to delve into research as an undergraduate. Although I learnt valuable remote sensing and GIS skills, I realized that for my graduate education I wanted to be based more in conservation and pursue field based research.

In 2001, I started my Masters at Yale. My research examined villages’ ecological footprint, livelihood activities and human-wildlife conflicts in Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary, a south Indian park. Fieldwork in 2002 began with a bang. A car accident on the second day resulted in a cracked kneecap and a cast on my leg. After 6 weeks, I was able to go back to the field. For this project I walked line transects (in pouring rain, rugged terrain, and getting bitten by leeches) to collect my ecological data and interviewed households about their activities and resettlement experience. This was my first opportunity to conduct independent research and experiences from being in this amazing park were unbeatable. I realized I wanted to be a conservation field scientist.

Mongabay: Estimating the extinction likelihood for some Indian mammals is a hugely ambitious project. How did this project come up?

Encroachment of forest at Nasehalla in Kudremukh National Park, Copyright: Niren Jain. |

Krithi Karanth: The idea for this came up as a result of discussions with my father Dr. Ullas Karanth. We were aware that many large mammals occurred very widely across India just 100 years ago. We were interested in comparing current and past distributions of species and factors that promote species persistence.

India has a very rich history, particularly natural history, taxidermy and hunting records. I was aware that the British had kept meticulous records of their field visits and hunting expeditions particularly for large mammals. I began to compile these records from over 50 museums, taxidermy firms, journals (Bombay Natural History and Indian Forester) which are more than 100 years old, gazetteers etc. I ended up a database with over 30,000 records for mammals alone.

This led to developing a survey to assess current presence/absence of species across India. Development of cutting edge occupancy modeling techniques at USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center spearheaded by Dr. Jim Nichols and others and collaborations with them led to adoption of these methods in my research.

EXTINCTIONS IN INDIA

Mongabay: What are the major threats to India’s mammals?

Krithi Karanth: The major threats are habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, poaching and local hunting, wildlife trade. Recent threats include massive infrastructure projects such as construction of highways, mines, dams and explosion of tourism (Karanth and DeFries 2011 in Conservation Letters is a new forthcoming paper on nature-based tourism in Indian parks).

Mongabay: Of the 25 mammals you examined which are in the most secure? Which are in the most trouble?

Wild Pig. Copyright: N. Samba Kumar. |

Krithi Karanth: I would not really classify any of them as secure. However some species such as lions, tigers, wild dogs or dholes, wild buffalo, gaur, mouse deer appear to be more threatened than others. Less vulnerable species appear to be jackal, wild pig, and black buck.

Mongabay: You found that the Asiatic lion and the swamp deer had both lost over 90% of their habitat. Is there any hope for these mammals?

Krithi Karanth: Both species appeared to have suffered declines prior to the 1900s and exist in very small populations. There is some effort to protect these species and so there is hope that they will persist. But their original ranges in India were never as widespread compared to tigers and leopards or even nilghai and chinkara.

Mongabay: The tiger has been receiving a lot of attention recently. India is considered probably the best stronghold for the tiger. According to the research what does the fate of the Bengal tiger look like?

Tiger Skin Seized at Nagarahole. May 2009. Copyright: Sharath Babu. |

Krithi Karanth: Tigers have received a lot of attention both within in India and globally. The financial investments that have gone to protect this species are tremendous. However, I feel there is a need to critical need to evaluate if the these vast sums of money are really needed, perhaps better management of existing funds is more necessary.

I am cautiously optimistic that tigers will continue to persist in the wild particularly in southern India where parks are well relatively protected. India has over 40% of the world’s tigers and is one of the most important tiger range countries. There is a lot of political will to conserve this species and these efforts are being renewed once again. Tigers continue to capture the imagination of people and are a great umbrella species that can be used to protect landscapes and other species. We have a new study examining tourist fascination with tigers and how they influence people’s willingness to visit parks in India. We find that tigers are really important for engaging public support for conservation.

Mongabay: What was one of the biggest surprises of your study?

Krithi Karanth: The declines of species are so dramatic, widespread and so recent. I wish I could have seen what the country was like in 1800s with all this wildlife. In many parts of India there is human tolerance for some species and this is why they still persist despite rapid changes in land use and high densities of people. This “cultural” tolerance must be harnessed.

Mongabay: What does the extinction probabilities of certain species tell you about the likelihood of a mass extinction?

Krithi Karanth: We examined local extinction of species and these cumulatively can indicate larger scale trends for extinction in both time and space.

Mongabay: How has the study been responded to in India?

Krithi Karanth: The study was covered by major newspapers The Hindu, Times of India and more than 50 science blogs and outlets. I am hoping that the Indian policy makers widen their conservation efforts to multiple species and larger landscapes.

CONSERVATION IMPLICATIONS

Mongabay: Given your findings what conservation measures would you recommend to save India’s mammals?

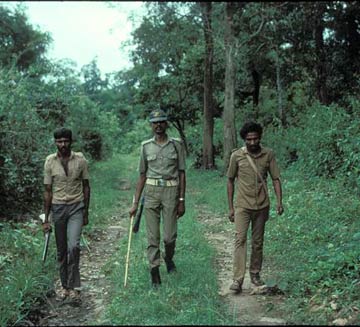

Field monitoring by forest department staff. Copyright:CWS/WCS-India. |

Krithi Karanth: Strengthening existing protected areas—perhaps establishing new protected areas in under represented habitats and focusing on species that are at most risk.

Cultural tolerance for wildlife has to be supported with provided effective compensation for local people affected by human-wildlife conflicts such as crop depredation and livestock predation. These people often bear the brunt of costs of living close to protected areas and rarely derive benefits from tourism.

The park staff also require our support, particularly guards-watchers who are tasked with the day to day monitoring of these parks but often lack the right equipment, clothing or basic living amenities inside the parks.

We also find that some species such as leopards, wolves, nilghai, blackbuck are found in large areas outside parks. Therefore, evolving conservation strategies outside parks for human-dominated landscapes will be very important to facilitate connectivity and movement of these species

Mongabay: Which species require new protected areas in order to thrive?

Nilgiri Thar. Copyright: Sanjay Gubbi. |

Krithi Karanth: A country with 1.2 billion people using 97% of land area leaves very little room to really establish new protected areas unless they are in remote or inaccessible places. As I said earlier improving existing parks along with better management of outside landscapes is a more realistic scenario. In a few critical habitat areas relocation of people might be useful if done in a responsible and equitable manner because for species such as wild dogs and tigers they have very few habitats remaining.

Mongabay: How positive are you that India will pursue a path that ensures the survival of its unique and high biodiversity?

Krithi Karanth: I am hopeful that we will have many of these species in India into the next century, but worry that multiple interests and lack of focus will undermine efforts. The rapid changes in land use due a growing economy and demands of its people places conservation interests at odds with infrastructural projects, commercial interests such as tourism and changing aspirations of people living in close proximity to wildlife are also serious challenges today.

Mongabay: What advice would you give a student interested in studying the relations between humans and biodiversity?

Black Buck. Copyright: Sanjay Gubbi |

Krithi Karanth: We need more people in the field with a passion for conservation and wildlife. There are so many ways to get involved beyond being a full time conservation practitioner or scientist, even as a volunteer. I was able to take 75 people as volunteers to ten Indian parks on my projects to assist in data collection in 2009. For me it was opportunity to engage with people from different fields and expose them to challenges of conservation in Indian parks. Among these people, 10 decided to pursue graduate education, many others took pictures, blogged about their experiences and many came away with new insights on wildlife tourism. It is wonderful that are so many interested and qualified young Indians who really care about nature and want to contribute meaningfully to conservation efforts in India.

So, I feel that conservation and wildlife are your passions pursue them.

Mongabay: What’s next for you?

Krithi Karanth: I am wrapping up a series of papers on different aspects of nature-based tourism and its implications in India.

I am pursuing new projects examining wildlife habitat use, human-wildlife conflicts, and evaluating status of Indian parks etc.

I currently work at the Centre for Wildlife Studies and National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore and with Columbia University in New York. I hope to use science to engage more with Indian conservation policy and management efforts, and broaden citizen science efforts in conservation.

CITATION: Krithi K. Karanth, James D. Nichols, K. Ullas Karanth, James E. Hines, and Norman L. Christensen Jr. The shrinking ark: patterns of large mammal

extinctions in India. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. March 2010. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0171.

Nilgai. Photo taken at Ranthambore. Copyright: Harshawardhan.

.

Dhole or Indian Wild Dog. Bandipur National Park. Copyright: Krishna Prasad.

.

Guar. Nagarahole. Copyright: Sanjay Gubbi

.

Asiatic Elephant. Nagarahole. Copyright: Sanjay Gubbi

.

Related articles

India pledges to protect cat-crazy rainforest

(02/14/2011) The Jeypore-Dehing lowland rainforest in Assam, India is home to a record seven wild cat species, more than any other ecosystem on Earth. While it took wildlife biologist Kashmira Kakati two years of camera-trapping to document the seven felines, the announcement put this forest on the map—and may very well save it. A year after the record was announced, officials are promising to pursue permanent preservation status for the forest, which is threatened by logging, poaching, oil and coal industries, and big hydroelectric projects.

Asia’s last lions lose conservation funds to tigers

(01/24/2011) The last lions of Asia and the final survivors of the Asiatic lion subspecies (Panthera leo persica) are losing their federal conservation funding to tiger programs, reports the Indian media agency Daily News & Analysis (DNA). While the Asiatic lion once roamed Central Asia, the Middle East, and even Eastern Europe, today the subspecies survives only in India’s Gir Forest National Park in the north-western state of Gujarat.

Hope remains for India’s wild tigers, says noted tiger expert

(09/30/2010) As 2010 marks ‘The Year of the Tiger’ in many Asian cultures, there has been global interest in the long-term viability of tiger populations in the wilds of Asia. Due to increasing pressures on remaining tiger habitats and a surge in demand for tiger parts from traditional medicine trades, many conservation experts consider the current outlook for wild tiger populations bleak. Dr Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) India does not share this view. He believes that a collaboration of global and local interests can secure a future for tigers in the wild.

(09/30/2010) As 2010 marks ‘The Year of the Tiger’ in many Asian cultures, there has been global interest in the long-term viability of tiger populations in the wilds of Asia. Due to increasing pressures on remaining tiger habitats and a surge in demand for tiger parts from traditional medicine trades, many conservation experts consider the current outlook for wild tiger populations bleak. Dr Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) India does not share this view. He believes that a collaboration of global and local interests can secure a future for tigers in the wild.