An Interview with AJ Patel, founder of the Hasla Mara Wildlife Conservation Foundation

The Masai Mara. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

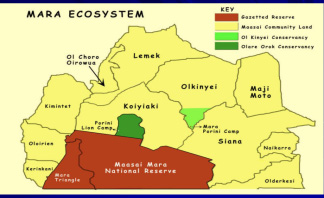

At the epicenter of East Africa’s Great Migration, the Masai Mara of Southern Kenya hosts one of the world’s great wildlife spectacles, as herds of over two million wildebeest, zebra, and gazelle congregate in search of fresh grazing brought by the annual rains. Yet, even here in one of the world’s great wild places, modern man casts a long shadow, and the Mara Ecosystem is degenerating under the pressures of uncontrolled tourism, divisive local politics, and the burgeoning population growth of the local Maasai people.

Working to reverse what seems to many conservationists a hopeless trend for the area, a champion of the Masai Mara has emerged in AJ Patel, founder of the Hasla Mara Wildlife Conservation Foundation. Building a career as a successful entrepreneur and civic leader in San Francisco Bay Area’s Silicon Valley, AJ now focuses his considerable business experience and skills for the cause of global wildlife conservation.

|

The Great Migration of the Serengeti and the Masai Mara. Video Courtesy of National Geographic |

The following article is an interview with AJ Patel, founder of the: Hasla Mara Wildlife Conservation Foundation.

An interview with AJ Patel of the Hasla Mara Conservancy Foundation

Mongabay: Tell our readers about the Hasla Mara Wildlife Conservation Foundation and your group’s work in the Masai Mara.

A local hero and honored elder for the Maasai people, AJ Patel, founder of the Hasla Mara Conservancy Foundation |

AJ Patel: A primary goal of the Hasla Mara Foundation is to develop a workable model for preserving the greater Masai Mara Ecosystem. To accomplish this objective, our project must step beyond the role of traditional land conservancies which tend to focus solely on “habitat conservation.” With the Mara the challenges are very broad and complex because different local interests groups have been at odds over the best use and development of the Mara. The Hasla Mara Foundation has stepped up less as a traditional conservation project and more as a community and conservation advocate group, which seeks to develop a unified approach for the Masai Mara by building inclusion and buy-in from the local Maasai people.

To reach this goal we have had to bring various local interest groups together under the business premise that the Mara is the only place on earth that still has this type of wildlife diversity and concentration. This is a local asset that cannot be replicated and a resource that can sell itself by creating value for local interests if presented correctly in the world marketplace.

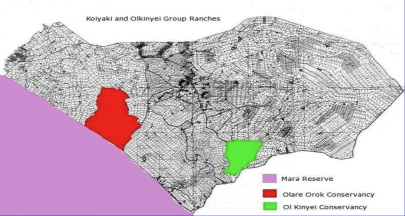

Two Thirds of the Masai Mara’s Ecosystem falls within various Maasai Tribal Community Ranches |

The Masai Mara could be a brand just like Coca Cola and there is no reason that the area could not generate enough income to sustain the local Maasai communities.

Mongabay: What threats does the Masai Mara Ecosystem currently face?

AJ Patel: The central issue for the Masai Mara is that only a third of the Mara Ecosystem is protected within the boundaries of the Masai Mara National Reserve. The remaining habitat falls under the control of various Maasai tribal community ranches, and these groups have not been in agreement on best use practices for the Mara.

Bella: one of the stars of the BBC’s “Big Cat Diary” Series filmed in the Masai Mara Photo Courtesy of the BBC.  Jonathan Scott of Big Cat Diary; A Leading Advocate of the Hasla Mara Conservancy Project. Photo Courtesy of the BBC |

And though there has been a thriving tourist industry within the Mara, in general, the local Maasai people have had limited participation in this revenue. From the Maasai’s perspective, there has been greater incentive to convert this wild habitat into agricultural or other (non wildlife) use.

Adding to the growing problems of revenue distribution and land use the Government of Kenya has created an even larger problem by subdividing the community ranches and giving title to hundreds of individual Maasai Families for micro-parcels of approximately 150 acres.

The Masai Mara Ecosystem cannot survive this level of fragmentation, and this could effectively end the world renowned Great Migration.

Mongabay: Your group has advocated a business approach to solving the problems of Masai Mara. Please tell our readers about this approach, and why you feel it is best suited for the challenges of the area.

Investing in the Future: New Maasai school classrooms built by the Hasla Mara Foundation |

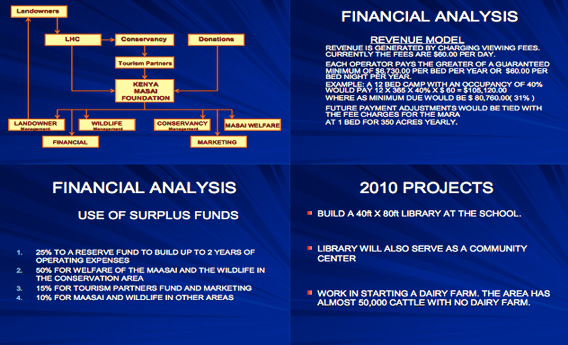

AJ Patel: Traditional conservation NGO groups have avoided working with the Masai Mara because of the complex local politics and perceived level of corruption within the area’s tourist industry. Our group has chosen to look at the problem as one of asset valuation, revenue participation, infrastructure investment, and building working synergies. The tourist industry, local government, and Maasai people’s real interests should be aligned in the best use management practices for the Masai Mara, and we believe that the best use is conservation of the Mara Ecosystem. To this end, our group has developed an inclusive revenue model which reflects both the needs and interests of the local tourist industry and Maasai tribal groups. The core of this strategy is to create incentives for the Maasai to not subdivide and parcel their lands but rather develop management practices that maintain the area’s integrity and create economic value in “wild spaces.” To foster this goal, we have put together a foundation that leases Maasai lands for conservation and works with “tourism partners” to generate revenue in support of this model. Revenues generated by our foundation are then allocated along the following lines:

– One third of revenues going directly to Maasai in the form lease payments (at higher rates of return than agriculture uses can yield)

– One third to management of the conservancy and habitat

– One third in the investment and development of future infrastructure

The Great Migration – or Subdivisions? |

I believe the third point, investment in future infrastructure, is in many ways the most important. Using tourism income to invest in the quality of the tourist experience (such as the improvement of roads, lodges, limits on uncontrolled vehicle traffic and game viewing, etc) will help maintain the area’s appeal. In any business, the more exotic a product, the higher price it commands. With the area’s fabulous wildlife, the local tourist industry and the Maasai have one of the best wildlife products in the world. Investing in this resource will benefit both groups.

Mara Photo Courtesy of Alan Root |

Furthermore, using foundation revenues to invest in the future of the Maasai people, through building of roads, schools, medical clinics, libraries, etc, gives the Maasai further incentive to maintain these wild lands.

It is a fundamental business practice to invest in, develop, and maintain a capital asset. In the case of the Maasai people, their primary capital asset is the Masai Mara Ecosystem.

In addition, by having a central (non-profit) foundation overseeing the various parts of our conservation model, there is a built-in system of transparency, checks and balances that mitigates the corruption that has plagued earlier efforts in the Mara.

The really good news, though, is that our model is working well and over a thousand Maasai families are directly benefiting from this project. And there have been strong benefits for local wildlife: the great herds are now using the areas preserved by our model, multiple lion prides have returned, and last week I received news that the critically endangered East African Black Rhino has been spotted in the Olare Orok Conservancy which has been protected by our model. This is a great victory for the Maasai people, our project’s partners, and local wildlife!

A Financial Model for the Masai Mara; Investing in the Future of the Maasai People Slides Courtesy of the Hasla Mara Foundation |

Mongabay: What are your future plans for the Hasla Mara Foundation?

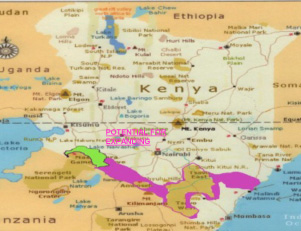

AJ Patel: To date, our model has conserved 130,000 acres of prime Mara habitat. In order to maintain the long-term viability of the Mara Ecosystem, we will need to conserve an additional 300,000 acres.

By design, I have taken the development of this project at a measured pace and have focused on the sound business practice of building solid working relationships. As they say,” You have to date before you get married.” The core challenge to working with the Maasai people was developing a trusting relationship. We had to walk our talk, we had to listen, we had to be inclusive, and we had to give back. The Maasai had heard promises from outside groups before. If we did not win the Masai’s vested interest in our project, it had no future. We have invested in the Maasai, and now they are eager to work with us. It has been a “win / win” for conservation and the Maasai people.

A Model that could be expanded across East Africa. Slide Courtesy of the Hasla Mara Foundation |

I would like to now build on our success by further investing in the future of the area and the Maasai. I am actively raising funds for a new library and would like to see the development of a dairy in an area that already holds over 50,000 cattle. And as we further prove our model, I am hoping that it could be expanded to work in other areas Africa and maybe even globally. Conservation needs to develop along the lines of including local people, not excluding them.

Mongabay: Mr. Patel, you are a successful entrepreneur and you helped found a very influential global business networking group called The Indus Entrepreneurs or “TIE” (http://www.tie.org/) Why are you now stepping up in the field of conservation, and why have you chosen to work with the Masai Mara?

AJ Patel: Although I was born in India, I spent most of my childhood in Uganda, until my family was forced to leave by Idi Amin’s government in 1972. Raised in East Africa, I have always had a great appreciation for wildlife and was drawn to return and give back to this area. And I strongly believe that a life well lived should really develop along three stages:

– Raising a family and building some personal wealth

– Helping communities build wealth and innovate

– Giving back on a local and global level

|

Wildlife Cinematographer Alan Root Speaks about the Mara and the Hasla Mara Conservancy |

East Africa is the acknowledged “cradle of humanity,” and I would argue that, in a sense, all people are East Africans. We share this common heritage. If our generation cannot save one of the last great wild places, like the Masai Mara, then we have really forgotten our past and in the process have failed future generations. I feel honor bound to use the organizational and messaging skills that I developed during my business career to help in an area that now has become my true calling.

|

Local Maasai Leader, Francis Nkoitoi Speaks About the Hasla Mara Conservancy |