This article was originally posted on Ecosystem Marketplace as Brazil’s Suruí Establish First Indigenous Carbon Fund.

A half-century ago, Brazil’s Suruí people knew little of the world beyond their cluster of villages – and nothing of the European settlers who dominated their continent. By 2006, that world beyond had engulfed them – a fact their young chief, Almir Narayamoga Suruí, saw all too clearly the first time he logged onto Google Earth.

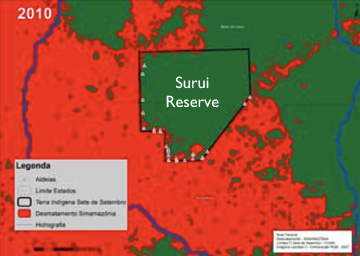

“Like everyone back then, I was curious to see my home from the sky,” he says. “But when I found the Suruí territory, it looked so lonely – like a little patch of green in a sea of brown and yellow.”

He believes, however, that in another half-century that little patch – their La Sete de Setembro in the state of Rondônia – will be more lush and green than at any time in recent memory, and his people will be healthier and better-educated than ever before, thanks to new schools and hospitals built with carbon cash earned by saving their forest and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD).

Surui Carbon Fund |

To achieve that vision, he and his people created the Suruí Fund, which the tribe’s marketing brochure describes as “a financial mechanism aimed at implementing the Management Plan of the Indigenous through principles of good governance and transparency, where representative indigenous advisers have a strong role” [“Suruí Carbon Brochure].

The Administrator

The Brazilian Biodiversity Fund (Funbio) structured the mechanism and will also administer it.

Funbio also oversees the Atlantic Forest Fund for the state of Rio de Janiero, as well as scores of other mechanisms for delivering environmental finance.

“Indigenous peoples have an outstanding track record in terms of forest stewardship, as has been demonstrated time and again by studies of conservation and deforestation rates, but they generally have less experience with managing the sorts of finance and investments that carbon market transactions entail,” says Jacob Olander, who is providing technical support as head of the Katoomba Incubator, a project of environmental non-profit Forest Trends (publisher of Ecosystem Marketplace). The incubator is designed to help local groups around the world develop expertise in payments for ecosystem services (PES), which are schemes designed to reward good land stewardship by recognizing the economic value of nature’s services.

|

“These sorts of mechanisms and partnerships can help provide specialized administrative support and credibility for investors,” he adds.

Over the first three years, Funbio will advise the Suruí on how to funnel carbon income into environmental projects – such as carbon-friendly agriculture and rainforest preservation. Over time, as carbon opportunities wane, they will shift to other businesses and investments that can generate a sustainable economy. All decisions, however, will be made by the Associação Metareilá do Povo Indígena Suruí, a representative body that the tribe set up to administer environmental resources.

The Partners

Over the past three years, Almir has brought in four other partners.

Forest Trends got the ball rolling with early legal assistance and PES training, then helped tribal leaders identify and vet local partners. It’s now helping find buyers for newly-trademarked “Suruí Carbon”.

“An outstanding lesson of the Suruí is their ability to forge partnerships and adopt new tools and strategies where needed,” says Olander. “They know what they’re good at and what they’re not good at, and they know how to harness outside expertise – whether that be creating an endowment fund, using Google and satellite technology, or harnessing carbon markets – in ways that keep them in control of the project and their forests.”

Equipe de Conservação da Amazônia (“Amazon Conservation Team”, or ACT Brasil) has a long-standing relationship supporting the Suruí, complementing Forest Trends´ carbon market expertise. They are responsible for making sure the tribe understands what it’s getting into and can demonstrate that understanding to investors. They also provide ongoing legal advice to the the Metareilá as well as anthropological and geoprocessing support.

Forest Trends and ACT are also seeding the fund with a cash infusion to pay for the kind of rigorous measurements and documentation needed to qualify for certification under the Voluntary Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCB).

The Associação de Defesa Etnoambiental (Association for Ethnoenvironmental Defense, or “Kanindé”) The is a Brazilian Amazon-based NGO that leads the biological survey and ethno-zoning processes and assists the Suruí in their reforestation plan.

Idesam, a Brazilian NGO which lead technical work for the CCB-Gold rated Juma REDD project, has been developing the technical design and forest inventory work to rigorously quantify the carbon benefits. They are also responsible for the Project Design Document (PDD), which investors will use when deciding whether or not to invest in Suruí Carbon.

“Everyone is watching this,” says Mauricio de Almeida Voivodic, Coordinator for Natural Forests with Brazil’s Program for Forest Certification (IMAFLORA). “The Suruí and Forest Trends are at the front of everything that’s happening with REDD in Brazil, and other tribes see this as a template that they can use to save their own forests and earn income.”

In the first three years, the fund will channel money into environmental services, such as forest protection and climate-safe agriculture. It will gradually shift to other livelihood activities and organizational strengthening. Beyond the first three years, the scheme becomes more flexible, with annual reviews by Suruí governors and advisors.

The Suruí will negotiate directly with buyers or brokers, and then designate the fund as the manager of proceeds.

The History

The project began in 2007, when Almir contacted Beto Borges, who runs the Forest Trends communities program, for advice on implementing his 50-year Management Plan. Borges then commissioned a survey of Brazil’s legal landscape to provide clarity on tribal rights to carbon income. That survey prompted a flurry of other tribal leaders to ask for guidance on starting REDD projects, and that led to a series of workshops to get them up to speed.

Almir, meanwhile, persuaded the four Suruí clans to forgo lucrative – and immediate – income from logging in exchange for less certain – and certainly delayed – income from REDD.

Related articles