An interview with Alasdair Cameron of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

A recent interview with Kirsten Conrad on how legalizing the tiger trade could possibly save wild tigers sparked off some heated reactions, ranging from well-thought out to deeply emotional. While, we at mongabay.com were not at all surprised by this, we felt it was a good idea to allow a critic of tiger-farming and legalizing the trade to officially respond.

The issue of tiger conservation is especially relevant as government officials from tiger range states and conservationists from around the world are arriving in St. Petersburg to attend next week’s World Bank ‘Tiger Summit’. The summit hopes to reach an agreement on a last-ditch effort to save the world’s largest cat from extinction.

It is not hyperbole to say the wild tiger is on the edge of extinction. Populations have plummeted by over 95% since 1990, leaving only an estimated 3,500 wild tigers surviving in the world. These animals are threatened on all sides by habitat loss, prey declines, and conflict with humans. However, one of the gravest threats remains poaching of tigers for traditional medicines and decorative items, such as skins. While, this trade has been largely illegal since 1975 (with a domestic ban in China in 1993), it has not yet stopped the decline in tiger populations.

Tiger skin. Photo courtesy of EIA. |

While, Kirsten Conrad argues that given the dire state of tigers worldwide, the international community should look into considering lifting the ban on tiger parts and tiger farming to undercut the black market, Alasdair Cameron, a campaigner with EIA, warned mongabay.com that legalizing the trade “could increase [demand], acclimatising consumers to an environment in which the trade in tiger body parts and derivatives is both normal and acceptable.”

Cameron argues that to save wild tigers the world must vastly improve enforcement and decrease demand for tiger parts through education and awareness. He says this strategy is not theoretical, but has been shown to be effective in places such as South Korea and Japan.

In a November 2010 interview with mongabay.com, Alasdair Cameron discussed the effectiveness of the ban on tiger parts; the need for improved enforcement, especially in China; why tiger farms are not the answer; and his hopes for the Tiger Summit in St. Petersburg.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALASDAIR CAMERON

Mongabay: It’s obvious after 35 years since the CITES ban tigers are in deeper trouble than ever. Why has the tiger ban not worked to save tigers so far?

Alasdair Cameron: First of all, it is not totally fair to say that the ban has not worked. It has worked in some areas (see below). It is fair to say that it has not reversed the decline of the tiger. There are a couple of reasons for this. The first is that a ban without enforcement is not a ban. China, probably the largest consumer of tiger products, is an example of this. Despite harsh penalties, in large areas of the country tiger products, and those of other Asian big cats, can be bought and sold easily, and often quite openly. According to a recent report by TRAFFIC, which monitors trends in the illegal wildlife trade, since 2001 there has been only one seizure in the four Chinese Provinces most implicated in the international tiger trade (Qinghai, Gansu, Tibet and Sichuan – a combined area the size of Argentina). This is despite the fact that a range of NGOs, journalists and campaigners have documented hundreds of skins of endangered big cats, including tigers, being sold and worn. I myself have traveled to the region and seen leopard, snow leopard and tiger products for sale in full view of local law enforcement. At the same time there are already tiger farms around the country illegally selling tiger bone wine and meat, and the government has so far failed to investigate them. What sort of a ban is that?

Wine made out of tiger bones for sale at Qinhuangdao Wild Animal Park in 2007. Photo copyright: EIA. |

The second reason is that bans must be backed up with complimentary efforts in other fields. For a start, the demand for tiger products must be tackled. Already, one of the largest markets for tiger skins among the Tibetan community has collapsed thanks to efforts by the Dalai Lama, but demand reduction must be maintained and also respond as new markets emerge. Non-trade issues are equally vital. Habitat loss fueled by illegal logging, industrial expansion and encroachment, along with revenge killings by locals in response to livestock loss, are major problems. It is only by addressing all the reasons for the tigers’ decline that we have a chance to bring this species back from the brink. Tiger farming does nothing to address those issues.

When discussing tiger trade and enforcement, it is important to realize that this is not the ‘drugs war’. This is not some sort of unwinnable conflict that defies even the best efforts. It is a relatively small trade involving a limited and apparently shrinking number of individuals, and with a bit of effort we could make a real difference.

Mongabay: Why do you think enforcement would be enough to tackle criminal markets?

Alasdair Cameron:No one has ever claimed that enforcement alone will be enough to tackle the criminal markets. It is one side of the equation. Education and demand reduction are just as important. A useful example is in South Korea and Japan. Both were formerly major consumers of tiger parts. However, following a ban in the early 1990s, they have enforced the law and although it took a while they are now no longer considered major destinations for tiger products. Neither has tiger farms, neither has a legal market.

Enforcement can make a difference by tackling the limited number of people involved in what is a fairly small scale trade. If NGOs such as EIA can use undercover work to expose the same individuals and networks operating year after year, the local police forces could do the same. In fact, they could take it further using controlled deliveries and the like to unpick entire chains of criminals. I will say again that this is not the drugs trade, it is not hopeless, and a bit of enforcement could go a long way. Sadly, in many places it has never really been tried.

Mongabay: Enforcement is far better in places like South Africa for rhinos and elephants, yet they are still poached at decade-high and unsustainable rates. How can enforcement ever truly tackle a black market underground trade with consumers who are willing to pay any amount?

Alasdair Cameron:Part of the problem is that those trying to tackle poaching are not receiving support from investigations and demand reduction programs at the consumer and trafficking ends of the market. Ivory from African countries is largely being shipped to East Asia. While large seizures are sometimes made in Asian ports, there continues to be a thriving street trade in illegal ivory. As with Asian big cat skins, I have seen illegal ivory on sale in full view of police forces. Also, the existence of a legal trade in ivory in China (one of two countries that has been legally allowed to import some ivory) has led to tremendous confusion over what is and is not acceptable, as well as a thriving trade in forged certificates demonstrating authenticity. At the same time as the street trade is allowed to continue unimpeded, there is little evidence that serious investigations are being undertaken into the syndicates behind the trafficking of ivory and other products from Africa to Asia.

With rhino horn, the situation is more serious. Again, though, the problem is that South Africa is largely having to fight it single-handed, purely by trying to restrict the supply. There needs to be a matching effort in the end-user countries. The main destination appears to be Vietnam, thanks to recent remarks by a Vietnamese government Minister that it could cure cancer. To the best of my knowledge, the Vietnamese government has made few efforts to dispel this idea, allowing rhino horn to be sold for a high price. If serious efforts were made to educate potential consumers, who knows what the result might be?

I don’t think anyone expects law enforcement to be perfect. The aim is to make it good enough to reduce the illegal trade to a low level, where it will not harm the populations of endangered species. In some ways this is already the case with South Africa’s elephants, where despite poaching the population continues to thrive.

Mongabay: What kind of enforcement is needed? Are range states able to provide and afford this?

Tiger bones. Photo copyright: EIA. |

Alasdair Cameron:This really is not rocket science. Many of the strategies we are advocating are relatively inexpensive and often require little more than international agreements to effectively pool resources and intelligence. In many cases they involve simply doing what has already been agreed, rather than just saying that it will be done. There does need to be a shift in mentality though. Enforcement efforts need to be expanded to include the consumers and traffickers of parts, and there needs to be a move away from doing simple seizures, towards investigations and prosecutions.

Specifically, tiger range countries need to create specialist operational multi-agency units to investigate wildlife crime and share information, along with a dedicated information facility to support prosecutors and the judiciary and the establishment of INTERPOL ‘wildlife desks’ in range states and consumer countries;

The declaration of permanent bans on the use of all tiger parts and derivatives by tiger range countries and consuming nations would send a clear message to the criminal networks controlling trafficking and the commercial entities leaking farmed tiger products onto the market of a zero-tolerance approach, reinforced by the destruction of stockpiles and public awareness campaigns.

Finally, judicial reform is essential to speed up the legal processes which at present can drag on for years, allowing prime suspects to be set free on bail and simply slip away back into the trade.

With regard to the issue of cost, while some tiger range countries will undoubtedly need external support to help them protect their biodiversity, it is worth remembering that China spent $31 billion on the Olympic Games, and India $2.6 billion on the Commonwealth Games. The priorities put forward in the St Petersburg program are estimated to cost $350 million over the next five years.

Mongabay: Why would tiger farming not satisfy demand thereby undercutting poaching in the wild?

Alasdair Cameron: Lots of reasons, many of which are dealt with in detail in the papers highlighted below. Demand is not fixed. It can grow or shrink in response to marketing cues. There was no market for five-blade razors or vitamin-enhanced water until advertisers persuaded us they were wonderful. Far from satisfying demand, we believe tiger farming could increase it, acclimatising consumers to an environment in which the trade in tiger body parts and derivatives is both normal and acceptable.

At the same time, tiger farming muddies the issue and creates a ‘gray’ market in which criminals trading in poached tigers can launder or traffic their goods with far greater ease, mixing those sourced illegally with those officially permitted. This already appears to be happening with the ivory trade where despite there being a large amount of legal ivory (from one-off sales) and mammoth ivory on the market, illegal trade remains.

There is also a question of the cost of raising a tiger. Estimates suggest that this is around $4,000 per tiger. Killing a wild tiger is very cheap. Hunters and poachers in India and other tiger countries are typically paid just a few hundred dollars to procure one, which may amount to a few tens of dollars each. The retail price of a tiger product would need to fall to a very low level to render tiger poaching and laundering pointless.

Finally, we have the evidence of other trades. Crocodiles are farmed extensively, yet they are still declining right across Asia. Turtles and deer are ranched and farmed for meat, yet they too are caught in the wild in their thousands. How many wild sheep or cattle roam Europe?

Mongabay: How would legalizing the trade through tiger farming increase demand by consumers?

Alasdair Cameron: The real question is why would tiger farming decrease demand? There were tiger farms before the tiger trade bans came in during the early 1990s, and they did not satisfy trade. There are still tiger farms illegally supplying trade on a significant scale, and they are not satisfying the trade. The point is that no-one knows exactly what would happen, if trade were fully legalized but there are a number of risks. Currently tiger products are the preserve of a social elite, and tiger bone in particular is not available to most people. In the event of widespread farming it is likely that more and more potential consumers will become exposed to tiger products (this is supported by market research in China). Some of these will not buy them, but many will. Legalization may also reduce the social stigma attached to consuming tiger products, or wildlife products in general, encouraging a general growth in demand. In fact it is possible that the availability of wild and farmed parts would lead to a ‘two-tier’ market, with premium wild products continuing to appeal to those with the money and influence to obtain them.

We can also assume that the owners of tiger farms will want to grow and expand their businesses indefinitely (in the mode of all other businesses), with accompanied advertising and product diversification. At what point will tiger farmers decide that their market is big enough, at what point will they be sure that they have sufficiently flooded it to ensure that there is no point in poaching a wild animal? Would it even be in the interests of tiger farmers to care about what happens to the wild tiger?

The bottom line is that tiger farming is a huge gamble, the downside of which would be to create an environment in which demand for tiger products soars and policing the tiger trade ban becomes almost impossible. This would place intolerable strain on wild tiger populations.

Mongabay: Aren’t tiger farms just another insurance policy against extinction?

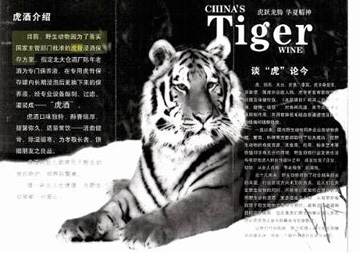

Leaflet accompanying tiger bone wine for sale at Qinhuangdao Wild Animal Park in 2007. Photo copyright: EIA. |

Alasdair Cameron:No, not really. The vast majority of them are of little or no value in terms of preserving wild tigers. There are strict guidelines for the captive breeding of animals for conservation purposes, few of which are met by the current tiger farms. To take one example, there are a five extant subspecies of tigers, each genetically different and with its own geographic range. In most of the tiger farms, the process of speed-breeding animals means that they are a hybrid of different subspecies. As such they cannot be entered into international breeding programs, nor can they be released.

Also, to put it bluntly, there are already too many tigers in captive breeding programs for conservation. These programs require surprisingly few animals and already reputable zoos are struggling to provide adequate environments for their captive tigers.

People sometimes ask if these tigers could be released into the wild. The simple answer is no. They would struggle to survive in the wild and would be danger to any humans they encounter (while they have the inherent skills to hunt they would likely hunt humans as ‘weak’ prey, and something they are used to encountering). There is also a lack of suitable habitat into which to release the tigers, and there is no prey for them to each. 5000 tigers would require a lot of space, and a lot of smaller animals to eat.

It is also important to reiterate one of the points made above. Tiger farming will do nothing to help with the wider threats to biodiversity in Asia. What threatens the tiger also threatens the leopard and snow leopard. Habitat loss, poor enforcement and corruption threaten all the forests and species of the region. We need a wide-ranging solution, not an attempt at a quick fix.

Mongabay: How do you bring down demand in Southeast Asia—where use of tiger parts go back millennia—in time to save the tiger?

Alasdair Cameron:Demand has already been reduced dramatically! South Korea, Japan and Taiwan are no longer serious consumers. Packaged and patented tiger bone medicines, which were traditionally the main source of demand for tiger products, are now very hard to find across Asia and there is little demand for them from the Traditional Asian Medicine community. The demand for skins used in traditional Tibetan costumes has also collapsed following the intervention of the Dalai Lama in 2006. Currently the main market for tiger, leopard and snow leopard products is as luxury items such as wall hangings or taxidermy, with a residual market in bone for medicinal purposes or claws and whiskers are charms. Putting a tiger skin rug on your floor is no more traditional in Asia than it is anywhere else. The bottom line is that those consuming countries that have made clear their intention to end the trade have largely done so, or at least reduced it to a low level.

Mongabay: What would be your ‘Dream Plan’ coming out of the meeting next week in St. Petersburg?

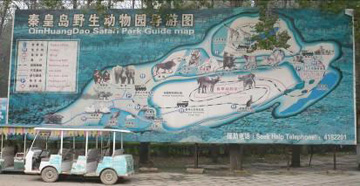

Qinhuangdao Wild Animal Park. Photo copyright: EIA. |

Alasdair Cameron: My dream would be for St Petersburg to mark a genuine watershed, not just in tiger conservation but in the protection of biodiversity in general. The only way that will happen is if there is serious commitment from the tiger range countries, not just from Ministries of Environment, but right throughout governments. It is easy to sign a document or make a declaration, what we need is real commitment. Most of the ideas on the table in St Petersburg have been around for over a decade. They are good, solid proposals. We need action.

Specific measures would include all tiger range countries setting up specialized, multi-agency wildlife crime units to tackle poaching, smuggling and sale of illegal tiger parts. They must also begin talking to each other, sharing information and intelligence. The importance of habitat protection must be made clear to all departments and provincial authorities. Right now, in most tiger countries, forests and protected areas are under constant pressure from logging, mining and other industrial interests, often supported by government departments and bodies. Finally, there must be serious efforts made on demand reduction, starting with an unequivocal message that the trade in tiger parts from all sources is illegal and will remain so.

Two Papers from EIA on Tiger Conservation:

Flawed Economics of Tiger Farms by Alasdair Cameron.

Tiger Farming Rebuttal by Justin Gosling.

Related articles

Would legalizing the trade in tiger parts save the tiger?

(11/15/2010) Just the mention of the idea is enough to send shivers down many tiger conservationists’ spines: re-legalize the trade in tiger parts. The trade has been largely illegal since 1975 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The concept was, of course, a reasonable one: if we ban killing tigers for traditional medicine and decorative items worldwide then poaching will stop, the trade will dry up, and tigers

will be saved. But 35 years later that has not happened—far from it. “Words such as ‘collapse’ are now being used to describe the [tiger’s] situation both in terms of population and habitat. Wild tiger numbers continue to drop so that we have about 3,500 today across 13 range states occupying just 7% of their original habitat. It’s universally acknowledged that we’re losing the battle,” Kirsten Conrad, tiger conservation expert, told mongabay.com in a recent interview.

Tiger farming and traditional Chinese medicine

(06/27/2010) The number of wild tigers has plummeted from 25,000-30,000 animals 50 years ago to around 3,200 today. A large part of the drop is from habitat loss and fragmentation. Tiger habitat has been reduced by 40 percent over the last decade, and tigers now occupy less than 7 percent of their historical range. Poaching has also contributed significantly to these dramatic population declines, particularly to supply parts for use in traditional medicine. In an interview with Laurel Neme, Grace Ge Gabriel, Asia Regional Director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), notes that, although the Chinese government has made significant efforts to reduce demand for tiger products by eliminating tiger bone from the official pharmacopeias, raising consumer awareness and identifying cheaper and more effective herbal alternatives to tiger bone for use in TCM, tiger farms threaten to reopen demand for tiger products by breeding tigers excessively, stockpiling tiger carcasses, and stoking demand by making and selling wine made from tiger bone.

Authorities confiscated over 1000 tigers in past decade

(11/09/2010) Highlighting the poaching crisis facing tigers, a new report by the wildlife trade organization, TRAFFIC, found that from 2000-2010 authorities have confiscated the parts of 1,069 tiger individuals, many of them dead. The tigers, or their body parts, were confiscated from 11 of the species’ 13 range countries, according to the report entitled Reduced to Skin and Bones. Yet the number only hints at the total number of tigers (Panthera tigris) vanishing in the wild due to the illegal trade in tiger parts for traditional Asian medicine and decorative items, such as skins.

Video: camera trap catches bulldozer clearing Sumatran tiger habitat for palm oil

(10/14/2010) Seven days after footage of a Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) was taken by a heat-trigger video camera trap, the camera captured a bulldozer clearing the Critically Endangered animal’s habitat. Taken by the World Wildlife Fund—Indonesia (WWF), the video provides clear evidence of forest destruction for oil palm plantations in Bukit Batabuh Protected Forest, a protected area since 1994.

Interpol pounces on tiger traffickers

(10/11/2010) INTERPOL, the world’s largest international police organization, is stepping up the fight to end the illegal tiger trade.

Hope remains for India’s wild tigers, says noted tiger expert

(09/30/2010) As 2010 marks ‘The Year of the Tiger’ in many Asian cultures, there has been global interest in the long-term viability of tiger populations in the wilds of Asia. Due to increasing pressures on remaining tiger habitats and a surge in demand for tiger parts from traditional medicine trades, many conservation experts consider the current outlook for wild tiger populations bleak. Dr Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) India does not share this view. He believes that a collaboration of global and local interests can secure a future for tigers in the wild.

Fighting poachers, going undercover, saving wildlife: all in a day’s work for Arief Rubianto

(09/29/2010) Arief Rubianto, the head of an anti-poaching squad on the Indonesian island of Sumatra best describes his daily life in this way: “like mission impossible”. Don’t believe me? Rubianto has fought with illegal loggers, exchanged gunfire with poachers, survived four days without food in the jungle, and even gone undercover—posing as a buyer of illegal wildlife products—to infiltrate a poaching operation. While many conservationists work from offices—sometimes thousands of miles away from the area they are striving to protect—Rubianto works on the ground (in the jungle, in flood rains, on rock faces, on unpredictable seas, and at all hours of the day), often risking his own life to save the incredibly unique and highly imperiled wildlife of Sumatra.

Tigers successfully reintroduced in Indian park

(09/27/2010) Poachers killed off the last Bengal tiger in India’s Sariska Tiger Reserve in 2004. Four years later, officials transferred three tigers from Ranthambhore National Park to Sariska in an attempt to repopulate the park with the world’s biggest feline. A new study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science evaluates the reintroduction by tracking radio-collared tigers and studying their scat.

Tigers discovered living on the roof of the world

(09/20/2010) A BBC film crew has photographed Bengal tigers, including a mating pair, living far higher than the great cats have been documented before. Camera traps captured images and videos of tigers living 4,000 meters (over 13,000 feet) in the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan.

Saving wild tigers will cost $82M/year

(09/15/2010) The cost of maintaining the planet’s 3,500 remaining wild tigers is around $80 million a year, according to a new study published in the journal PLoS Biology.

Guilty verdict over euthanizing tigers in Germany touches off debate about role of zoos

(08/11/2010) In June a German court handed down a guilty verdict to the Magdeburg Zoo director, Kai Perret, and three employees for euthanizing three tiger cubs in 2008. The zoo decided to kill the cubs when it was discovered that the cubs’ father was not a 100 percent Siberian tiger (i.e. he was a mix of two different subspecies). This is generally standard practice at many zoos around the world as animals that are not ‘genetically pure’ are considered useless for conservation efforts. However, the court found the workers guilt of breaking animal rights laws, finding that there was “no sufficient reasons to kill less valuable, but totally healthy animals.”

Myanmar creates world’s largest tiger reserve, aiding many endangered Southeast Asian species

(08/04/2010) Myanmar has announced that Hukaung Valley Tiger Reserve will be nearly tripled in size, making the protected area the largest tiger reserve in the world. Spanning 17,477 square kilometers (6,748 square miles), the newly expanded park is approximately the size of Kuwait and larger than the US state of Connecticut.

Plight of the Bengal: India awakens to the reality of its tigers—and their fate

(06/06/2010) Over the past 100 years wild tiger numbers have declined 97% worldwide. In India, where there are 39 tiger reserves and 663 protected areas, there may be only 1,400 wild tigers left, according to a 2008 census, and possibly as few as 800, according to estimates by some experts. Illegal poaching remains the primary cause of the tiger’s decline, driven by black market demand for tiger skins, bones and organs. One of India’s leading conservationists, Belinda Wright has been on the forefront of the country’s wildlife issues for over three decades. While her organization, the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), does not carry the global recognition of large international NGOs, her group’s commitment to the preservation of tigers, their habitat, and the Indian people who live with these apex predators, is one reason tigers still exist.

Malaysia introducing tough new wildlife laws

(05/20/2010) By the end of the year, Malaysia will begin enforcing its new Wildlife Conservation Act 2010 including stiffer penalties for poaching and other wildlife-related crimes, such as first time punishments for wildlife cruelty and zoos that operate without license.

The Critically Endangered South China Tiger Roars Again in 2010, the Chinese Year of the Tiger

(02/14/2010) Today marks the Chinese New Year for 2010, and the start of the traditional Year of the Tiger. The people of China might be celebrating future Years of the Tigers without their native and critically endangered South China Tiger (Panthera tigris amoyensis) if not for the efforts of Save China’s Tigers (SCT) a grassroots conservation effort headed by the charismatic Li Quan and her husband Stuart Bray. Both Ms Quan and Mr. Bray are former senior executives in international business circles. After leaving the corporate world, Ms Quan and Mr. Bray are now stepping up as champions for China’s natural environment, much of which has been lost in the Chinese march towards “The Four Modernizations.”

India to track every tiger death on-line

(02/07/2010) Due to increased problems with poaching, the conservation organization TRAFFIC has joined with the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) to begin tracking every tiger mortality in India with a new website called Tigernet.