As the world’s population increases, a surge in the number of older adults and the movement of people from the countryside to crowded cities will significantly affect levels of carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, according to a sweeping study published in the 11 October issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A significant but attainable slowing of the planet’s growing population could achieve up to 29 percent of the total decrease in emissions needed to stave off the harmful consequences of climate change by 2050, according to the study. But population growth isn’t the whole story, said lead author Brian O’Neill, a climate change researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Most previous studies focused just on population size without considering other factors, O’Neill said. This has led to debates about the extent to which population affects emissions, as people assume that “their favorite interactions that were left out of the analysis would totally change the result,” he said.

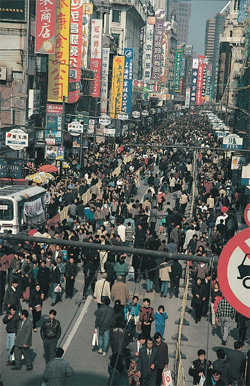

As more people move to large Asian cities like Shanghai by 2050, carbon emissions could increase by 25 percent. Image credit: Codrington, Stephen. Planet Geography 3rd Edition (2005) |

O’Neill said he and his colleagues modeled the effects of the major factors that would affect emissions, using data from 34 countries. Apart from the number of older people and the level of urbanization in a population, they also estimated other factors such as the number of people in each household, how many of them work, and how much energy and food they each consume. “This is the first global analysis where we put all the pieces together,” O’Neill said.

Incorporating all these factors bolstered the accuracy of the study’s estimates, commented Jianguo Liu, director of the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability at Michigan State University, in an email to mongabay.com. Liu was not involved in the research.

The study found that developing countries would have a lot more people living in cities by 2050. This usually means more people working and contributing to economic growth, which could increase emissions by more than 25 percent. As the economy grows, everyone’s income goes up, everyone’s consumption goes up, and energy use for an entire country goes up, O’Neill said.

The researchers also found that particularly in industrialized countries, there would be more older people who no longer work, which could reduce emissions by 20 percent.

“These authors are trailblazers. These first results are baby steps, but critically important ones,” climate scientist Richard Somerville of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego told mongabay.com via e-mail.

Follow-up studies would collect more data, such as the actual rate of population shifts to cities, to allow the researchers to increase the accuracy of their projections. Nevertheless, O’Neill said he hoped the study would put the debate about population and climate change on a firmer footing.

But Betsy Hartmann, director of the population and development program at Hampshire College, told mongabay.com via e-mail that she is wary of population-control policies that focus on saving the environment. Such policies “have a long and sordid history” and are typically focused on reducing women’s fertility as fast and cheaply as possible, Hartmann said. “At their worst, they are directly coercive,” she noted.

O’Neill maintained that there are examples of successful non-coercive population policies. His team’s paper doesn’t support coercive population control in any way, he added.

The bottom line, O’Neill said, is that climate policies should take into account the many other factors that contribute to carbon emissions. “Population is an important piece of the climate change puzzle, but it’s not the whole picture by any means,” he said.

CITATION: Brian C. O’Neill, Michael Dalton, Regina Fuchs, Leiwen Jiang, Shonali Pachauri and Katarina Zigova. Global demographic trends and future carbon emissions. PNAS published online 11 October 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004581107.

Sandeep Ravindran is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Related articles