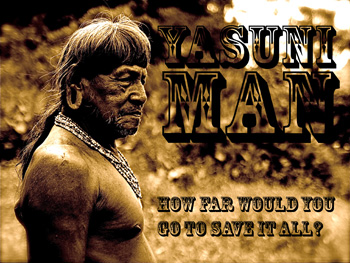

An interview with wildlife documentarian Ryan Killackey.

How do you save one of the most biologically and culturally diverse places in the world if most people have never heard of it? If you want a big audience—you make a film. This is what wildlife-filmmaker Ryan Killackey is hoping to do with his new movie Yasuni Man. Killackey says the film will show-off the wonders of Yasuni National Park while highlighting the complexity of its biggest threat: the oil industry.

“Conceptually, the film resembles a true-life cross between the documentary Crude and the blockbuster Avatar—except it’s real and it’s happening now,” Killackey told mongabay.com.

Located in eastern Ecuador, Yasuni National Park is world-renowned for its rich diversity of species, which may be the greatest on the planet.

|

“It’s the only place known to have world records for sheer numbers of mammals, birds, amphibians and plants. One acre of Yasuni has more species of trees than all of North America,” Killackey says

But Yasuni is not just notable for its stunning biodiversity, but its people. Home to three indigenous tribes, including uncontacted peoples, Killackey’s film will focus on the Waorani people who have a long history of battling oil companies, at times violently.

“The Waorani are my subjects because they’re an ancient culture caught in the middle of this modern conflict, and I’ve had personal contact with them for five years now. They’re also amazingly personable and affectionate people. There are some hugely entertaining personalities among the people living in community, and they’re trying to remain positive while facing this historic, even existential, challenge,” Killackey says.

However, much like Yasuni itself, Killackey’s film is facing obstacles, in this case: funding.

“Yasuni is one of the most treacherous and isolated places anywhere on the planet, which makes it expensive to access. We need specialized equipment that can survive the downpours and the mud and the elements. To give the audience the experience of being in this place, we’ll be using really fun toys like tiny HD cameras that fit on a spear-tip. So we’re racing to raise an additional $40,000 by October 9th, so I can assemble the gear and the crew and get down there to shoot the first sequence. This is a documentary, so it’s real life. The story’s unfolding as we speak,” Killackey says.

Killackey spoke to mongabay.com in October about his travels in Yasuni National Park, the threats to this unique place, his unfinished film, and the scene he thinks viewers won’t soon forget.

INTERVIEW WITH RYAN KILLACKEY

Mongabay: Why make a film about the Waorani people?

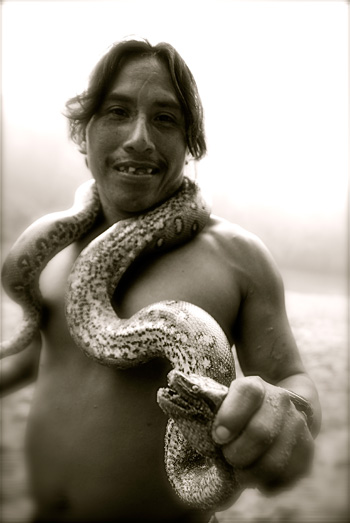

Waorani man with anaconda. Photo by: Ryan Killackey. |

Ryan Killackey: In 2005, I moved to Ecuador to make a film on amphibian decline and to work as an Amazon guide. Over the year, I made a three-part independent film series entitled Looking into the Eye of Extinction, on Ecuador, the Andes and the Galapagos. It was while producing this that I trekked into Yasuni National Park and filmed Dr. Morly Read, a British herpetologist living in Ecuador and who was monitoring amphibian populations. Our guides were Waorani from a community just off the Maxus Road that cuts into the heart of Yasuni. While filming, I observed the destruction that oil drilling has brought to the region and saw how the indigenous communities were directly impacted.

The Waorani are a community of indigenous people living within Yasuni Man Biosphere Reserve—a UNESCO World Heritage Site—along with two other warring tribes, the Tagaeri and Taromenane, who live in voluntary isolation with no peaceful contact with the outside world. The film isn’t entirely about the Waorani, but more so about the geopolitics of drilling in arguably the most biodiverse wilderness on Earth, and its impact on both the array of wildlife and these indigenous communities.

The Waorani are my subjects because they’re an ancient culture caught in the middle of this modern conflict, and I’ve had personal contact with them for five years now. They’re also amazingly personable and affectionate people. There are some hugely entertaining personalities among the people living in community, and they’re trying to remain positive while facing this historic, even existential, challenge.

This past December and January, I went into the heart of the reserve and stayed at three villages. I met dozens of amazing people who needed someone to tell the world about their communities’ struggle to survive this onslaught by the industrialized world.

Mongabay: What makes Yasuni unique and what is threatening it?

Ryan Killackey: The biological and cultural diversity is the most unique feature of the reserve. The species richness is spectacular, making Yasuni arguably the most biologically diverse region of the planet. It’s the only place known to have world records for sheer numbers of mammals, birds, amphibians and plants. One acre of Yasuni has more species of trees than all of North America. Also, how many places still have uncontacted communities of indigenous people who live untouched by the hand of the Western world? These conditions exist nowhere else on Earth. That’s special.

Oil extraction is the greatest threat to the entire region. The spilling of oil is of course devastating to wildlife and humans living in the area. Chevron/Texaco has been entangled in a lawsuit for nearly 2 decades for spilling millions of gallons of crude oil into a terrestrial freshwater habitat.

Spills are obviously a huge threat, and the construction of roads is equally detrimental. Roads bring colonization, spread and transmit disease to wildlife and indigenous communities, make it easier to hunt isolated wildlife populations, increases deforestation through illegal logging concessions, among other impacts. The roads also fragment species habitats, creating deadly barriers for the wildlife that can’t cross them—monkeys that travel through the forest canopy and small amphibians, for example.

Mongabay: How have you gained access to this remote region and these incredible people?

Screech owl in Yasuni. Photo by: Ryan Killackey. |

Ryan Killackey: Ecuador’s a spectacular place. If you love wildlife and are looking for adventure, opportunities will find you if you let them. Over the course of my 17 months there, I’ve met several biologists and conservationists who opened many of the doors for me. It’s critical to keep an open mind and to look for the story. I have also been aided by two of my closest friends in Ecuador, Tom Quesenberry and Mariela Tenorio, the owners of El Monte Lodge in Mindo. They have been working directly with the Waorani to establish ecotourism in Waorani territory as an alternative to drilling and deforestation.

The region where I’ll film is only accessed through a long hike through the thick forest, followed by a two-and-a-half day motorboat ride down the Cononaco River. Once there, I’m always with a Waorani guide who lives and subsists in the forest. I never go alone, as this is actually hostile tribal territory.

Mongabay: Can you tell us about a scene in your film that you can’t wait for people to see?

Ryan Killackey: There is one scene where the Jaguar shaman will prepare and ingest ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic drug. He will then transform into a jaguar and tell us about the 200 mile journey that we are about to embark upon.

I can’t tell too much, but I also promise an epic conclusion. The viewer will feel what it takes to survive in a world where the odds are stacked a mile high against you. I’m a wildlife filmmaker, so you’ll have heart-stopping encounters with some of the weirdest, most magnificent and sometimes deadly animals anywhere. You’ll also grasp the true complexity of the geopolitical situation—the stakes that all the various factions have in the future of Yasuni. Not only the Waorani and the wildlife and the energy companies, but Ecuador’s President Correa and his cabinet, the UN system, and the whole cast of activists, lobbyists, scientists, shamans. Conceptually, the film resembles a true-life cross between the documentary Crude and the blockbuster Avatar—except it’s real and it’s happening now.

Mongabay: What obstacles do you face before the film can be finished?

Ryan Killackey: The film’s all ready to shoot. All the pieces are in place—the storyline, the budget, my collaborators—everything except funding. Yasuni is one of the most treacherous and isolated places anywhere on the planet, which makes it expensive to access. We need specialized equipment that can survive the downpours and the mud and the elements. To give the audience the experience of being in this place, we’ll be using really fun toys like tiny HD cameras that fit on a spear-tip. So we’re racing to raise an additional $40,000 by October 9th, so I can assemble the gear and the crew and get down there to shoot the first sequence. This is a documentary, so it’s real life. The story’s unfolding as we speak. So far, we’ve raised $20,000 from over 200 backers. We need more people to become involved in telling this story. If we’re successful, we can get enough eyes on what’s happening to have a real shot at protecting Yasuni.

For more information: Yasuni Man.

To donate: Fundraising.

Waorani boy in Yasuni. Photo by: Ryan Killackey.

Related articles

A look at Ecuador’s agreement to leave 846 million barrels of oil in the ground

(09/13/2010) Ecuador’s pioneering initiative to voluntarily leave nearly a billion barrels of oil under Yasuní National Park, an Amazonian reserve that is arguably the most biodiverse spot on Earth, took a major step forward in early August when the government signed an accord with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for the long-awaited establishment of a trust fund. The signing event generated a wave of international media attention, but there has been very little scrutiny of what was actually signed. Here we present an initial analysis of the signed agreement, along with a brief discussion of some of the potential caveats. Due to the precedent-setting nature of this agreement, attention to the details is now of the utmost importance.

Bold rainforest idea makes good: Ecuador secures trust fund to save park from oil developers

(08/03/2010) In what may amount to a historic moment in the quest to save the world’s rainforests and mitigate climate change, Ecuador and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDF) have created a trust fund to protect one of the world’s most biodiverse rainforests from oil exploration and development. The fund will allow the international community to pay Ecuador to leave an estimated 850 million barrels of oil in Yasuni National Park in the ground instead of extracting it. This first-of-its-kind agreement, known as the Yasuni-ITT Initiative, will allow the rainforest protected area to remain pristine: preserving one of the most species-rich places on Earth, safeguarding the lives of indigenous people, and keeping an estimated 410 million tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

Oil devastates indigenous tribes from the Amazon to the Gulf

(07/27/2010) For the past few months, the mainstream media has focused on the environmental and technical dimensions of the Gulf mess. While that’s certainly important, reporters have ignored a crucial aspect of the BP spill: cultural extermination and the plight of indigenous peoples. Recently, the issue was highlighted when Louisiana Gulf residents in the town of Dulac received some unfamiliar visitors: Cofán Indians and others from the Amazon jungle. What could have prompted these indigenous peoples to travel so far from their native South America? Victims of the criminal oil industry, the Cofán are cultural survivors. Intent on helping others avoid their own unfortunate fate, the Indians shared their experiences and insights with members of the United Houma Nation who have been wondering how they will ever preserve their way of life in the face of BP’s oil spill.

Photos: park in Ecuador likely contains world’s highest biodiversity, but threatened by oil

(01/19/2010) In the midst of a seesaw political battle to save Yasuni National Park from oil developers, scientists have announced that this park in Ecuador houses more species than anywhere else in South America—and maybe the world. “Yasuní is at the center of a small zone where South America’s amphibians, birds, mammals, and vascular plants all reach maximum diversity,” Dr. Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland said in a press release. “We dubbed this area the ‘quadruple richness center.'”

Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon

(09/13/2009) The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call “one of the most species diverse forests in the world”—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest.