- In all the discussions of saving the world’s biodiversity from extinction, one point is often and surprisingly forgotten: the importance of the world’s species in providing humankind with a multitude of life-saving medicines so far, as well as the certainty that more vital medications are out there if only we save the unheralded animals and plants that contain cures unknown.

- Already, species have provided humankind everything from quinine to aspirin, from morphine to numerous cancer and HIV-fighting drugs. “As the ethnobotanist Dr. Mark Plotkin commented, the history of medicine can be written in terms of its reliance on and utilization of natural products,” physician Christopher Herndon told mongabay.com.

- Herndon is co-author of a recent paper in the journal Biotropica, which calls for policy-makers and the public to recognize how biodiversity underpins not only ecosystems, but medicine.

An interview with Dr. Christopher N. Herndon.

In all the discussions of saving the world’s biodiversity from extinction, one point is often and surprisingly forgotten: the importance of the world’s species in providing humankind with a multitude of life-saving medicines so far, as well as the certainty that more vital medications are out there if only we save the unheralded animals and plants that contain cures unknown. Already, species have provided humankind everything from quinine to aspirin, from morphine to numerous cancer and HIV-fighting drugs.

“As the ethnobotanist Dr. Mark Plotkin commented, the history of medicine can be written in terms of its reliance on and utilization of natural products,” physician Christopher Herndon told mongabay.com. Herndon is co-author of a recent paper in the journal Biotropica [PDF], which calls for policy-makers and the public to recognize how biodiversity underpins not only ecosystems, but medicine.

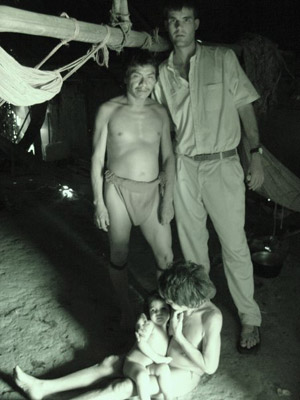

Christopher Herndon with Eñepa healer and family in Venezuela. Photo courtesy of Christopher Herndon. |

“Our dependence today on nature for health has not diminished as significantly as commonly presumed. Over the past quarter century, more than half of all pharmaceuticals brought to market were directly derived from or modeled after compounds from other species,” Herndon explains.

However, the ecosystems that have yielded some of the world’s most important and promising drugs—such as rainforests and coral reefs—are also among the most endangered. Researchers worry that in face of ocean acidification and warming temperatures connected to climate change, few coral reefs will outlive the century. Meanwhile, the world’s rainforests continue to vanish at astounding rate, estimated at 80,000 acres (32,300 hectares) every day due to commercial agriculture, livestock, logging, slash-and-burn farming, and massive development projects.

In face of such destruction, Herndon says it’s truly difficult to know how many species have been tested for medicinal properties, or for that matter how many have already been lost forever.

“Scientists generally estimate that less than one percent of all species has been fully examined for medical potential. We are only just beginning to appreciate the staggering biodiversity of our planet. A significant portion remains to be discovered by mankind.”

Making conservation even trickier, most of nature’s medicine cabinet is not stored in big charismatic mammals, such as tigers and elephants, but among the unsung heroes of world’s ecosystems: plants, fungi, and invertebrates.

“The organisms that offer the greatest hope to ameliorate human suffering are rarely the most charismatic or cuddly. Unlikely to be profiled in a wall calendar anytime soon, they are often toxic or inhabit the extraordinary microcosms that exist below the limits of the naked eye and the scope of appreciation for many. To save their medical potential, we need to preserve entire ecosystems—we simply cannot predict which species and in what ways they will yield medical breakthroughs,” Herndon says.

So, why has everyone—policy-makers, conservationists, doctors, and drug-companies included—failed to recognize this hugely compelling reason to preserve the world’s ecosystems?

“Generally speaking, there is a prevailing misconception that biotechnology and synthetic chemistry has somehow supplanted our dependence on the natural world. The potential of nature has not diminished—arguably, it has only enhanced as we gain the technological tools to more efficiently access and utilize its potential for our benefit,” Herndon says.

Herndon spoke to mongabay.com in an October interview about the connection between biodiversity and medicine, including amazing past discoveries, vital species and ecosystems, and why society continues to undervalue nature’s medicine cabinet.

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRISTOPHER HERNDON

Mongabay: When people think of animals and plants, they usually don’t think of health. How is biodiversity connected to human health? What are some examples?

Strange plant on Mount Kenya. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Christopher Herndon: People have been using species from nature as medicine since the dawn of history. Medicinal plants dating from over 60,000 years ago have been found in an Iraqi cave site. A fur strap found on the wrist of the 5,000 year-old Ice Man from the Alps contained threaded fragments of a birch fungus species known to have antimicrobial properties.

As the ethnobotanist Dr. Mark Plotkin commented, the history of medicine can be written in terms of its reliance on and utilization of natural products. The examples are innumerable—from aspirin to morphine to lovastatin. Our dependence today on nature for health has not diminished as significantly as commonly presumed. Over the past quarter century, more than half of all pharmaceuticals brought to market were directly derived from or modeled after compounds from other species. Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that in many developing countries as much as 80% of the population relies on traditional therapeutics sourced from nature.

More broadly, environmental health is a major determinant of our well-being. One cannot think of the harsh medical realities in Haiti without appreciating that 97% of the half-island country is deforested and much of the land eroded away. The border between Haiti and the adjacent Dominican Republic can be viewed from satellite as an abrupt transition from brown to green. Human diseases are exacerbated through ecologic disturbance. As we encroach into ecosystems, we acquire pathogens from other species. These are not trivial or esoteric diseases—HIV, for example, is the greatest pandemic of the modern era.

Mongabay: Approximately what percentage of known species has been tested for medicinal value?

Christopher Herndon: It is difficult to precisely quantify. Scientists generally estimate that less than one percent of all species has been fully examined for medical potential. We are only just beginning to appreciate the staggering biodiversity of our planet. A significant portion remains to be discovered by mankind.

Mongabay: Besides rainforests, what other ecosystems have yielded important medicines?

Herndon evaluating a sick child with local Eñepa healer in Venezuela. Photo courtesy of: Christopher Herndon. |

Christopher Herndon: Tropical rainforests are probably the most celebrated ecosystem as a repository of new medicines. Although comprising only 6% of the earth’s land surface, they contain over half of its terrestrial biodiversity. Pharmaceuticals have been developed from species from a diversity of ecosystems. The synthesis of AZT, the first effective treatment for HIV, was guided by compounds isolated from a Caribbean sponge. Taxol was discovered from temperate forests in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Digitalis was discovered from an English garden plant. Any ecosystem can contain species that may contribute to health and biomedical science.

Mongabay: Why does preserving future medicines mean saving some of the world’s less popular species?

Christopher Herndon: The organisms that offer the greatest hope to ameliorate human suffering are rarely the most charismatic or cuddly. Unlikely to be profiled in a wall calendar anytime soon, they are often toxic or inhabit the extraordinary microcosms that exist below the limits of the naked eye and the scope of appreciation for many. To save their medical potential, we need to preserve entire ecosystems—we simply cannot predict which species and in what ways they will yield medical breakthroughs. Who would have guessed that the salivary venom of the gila monster would lead to an FDA-approved treatment for diabetes? Or that the sting of a Arabian desert scorpion would contain a toxin that selectively binds cells of an aggressive form of brain cancer that is largely refractory to therapy? The natural world is out there for our discovery if only we have the wisdom to not discard it.

Mankind’s need to develop new medicines is not a quixotic quest but rather a timeless struggle. Speaking as a physician, there are few conditions in medicine for which we are overburdened with too many safe, highly efficacious and inexpensive treatments. It is common need for which all of humanity can directly and tangibly share in its benefit. Although a large portion of the population of the developing world—regions containing the greatest extent of our planet’s terrestrial biodiversity—may not be able to access a novel and expensive cancer therapy, they can benefit from pharmaceuticals that target their extensive disease burdens. A contemporary example is artemisinin—a medication derived from a Chinese herb and the most effective treatment for malaria that exists. In 2001, artemisinin-based therapies were adopted by the World Health Organization as the first-line agent in its global fight against malaria.

Mongabay: Why do you think the connection between biodiversity and health is underappreciated? In other words, why are drug companies, cancer non-profits, and physician associations not up in arms over the loss of ecosystems and our future medicines?

Researchers worry that the Great Barrier Reef in Australia may not survive the century. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Christopher Herndon: In medical school, there is little emphasis on how treatments were developed or discovered. How many internists are aware that the groundbreaking blood pressure medicine captopril, one of the best-selling drugs of all time, was developed through the study of the venom of a Brazilian viper? I would like to think practitioners would be more prudent with antibiotic use if they better appreciated the perspective that these miracle drugs—the vast majority of which are derived from nature—are the product of millions of years of evolutionary selection. It is of grave concern that we are burning through them within a timeframe of decades—not even a blink of an eye on an evolutionary scale.

Generally speaking, there is a prevailing misconception that biotechnology and synthetic chemistry has somehow supplanted our dependence on the natural world. The potential of nature has not diminished—arguably, it has only enhanced as we gain the technologic tools to more efficiently access and utilize its potential for our benefit.

Several recent op-ed pieces have lamented the lack of therapies resulting from the sequencing of the human genome. This should not have been surprising—at least in the short term. The Human Genome Project and our ever-deepening understanding of molecular biology are extraordinary achievements that advance a foundation of science. There exists, however, a wide gap between knowledge and therapeutics that enhance lives. Nature has designed and tested novel and highly effective bioactive compounds for 3.5 billion years. Many of the natural compounds that have changed medicine could never have been conceived even today by the most imaginative synthetic chemists. The natural world is an endowment fundamentally worth protecting.

Citation: Christopher Herndon and Rhett Butler. Significance of Biodiversity to Health. Biotropica. 42(5): 558–560 2010 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00672.x.

Related articles

Mass extinction fears widen: 22 percent of world’s plants endangered

(09/28/2010) Scientific warnings that the world is in the midst of a mass extinction were bolstered today by the release of a new study that shows just over a fifth of the world’s known plants are threatened with extinction—levels comparable to the Earth’s mammals and greater than birds. Conducted by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; the Natural History Museum, London; and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the study is the first time researchers have outlined the full threat level to the world’s plant species. In order to estimate overall threat levels, researchers created a Sampled Red List Index for Plants, analyzing 7,000 representative species, including both common and rare plants.

The role of wildlife conservation in human health

(09/07/2010) Livestock farming is an important traditional way for communities in sub-Saharan Africa to build and maintain wealth, as well as attain food security. Essentially, the transfrontier or transboundary conservation areas (TFCA) concept and current internationally accepted approaches to the management of transboundary animal diseases (TADs) are largely incompatible. The TFCA concept promotes free movement of wildlife over large geographic areas, whereas the present approach to the control of TADs (especially for directly transmitted infections) is to use vast fences to prevent movement of susceptible animals between areas where TADs occur and areas where they do not, and to similarly restrict trade in commodities derived from animals on the same basis. In short, the incompatibility between current regulatory approaches for the control of diseases of agro-economic importance and the vision of vast conservation landscapes without major fences needs to be reconciled in the interest of regional risk-diversification of land-use options and livelihood opportunities. An integrated, interdisciplinary approach offers the most promising way to address these issues—one where the well-being of wildlife and ecosystems, domestic animals, and Africa’s people are assessed holistically, with a “One World – One Health” perspective.

(06/14/2010) If someone saves your life, you want to express your gratitude however you can — a gesture, a “thank you,”, or somehow returning the favor. Yet when you owe your life to a plant found thousands of miles away, the task becomes much harder. As a nurse, I’ve known for years that many life-saving medicines come from plants and animals found around the world. But I never thought that one day I would have to rely on the bark of a rare Asian tree to survive.

How rainforest shamans treat disease

(11/10/2009) Ethnobotanists, people who study the relationship between plants and people, have long documented the extensive use of medicinal plants by indigenous shamans in places around the world, including the Amazon. But few have reported on the actual process by which traditional healers diagnose and treat disease. A new paper, published in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, moves beyond the cataloging of plant use to examine the diseases and conditions treated in two indigenous villages deep in the rainforests of Suriname. The research, which based on data on more than 20,000 patient visits to traditional clinics over a four-year period, finds that shamans in the Trio tribe have a complex understanding of disease concepts, one that is comparable to Western medical science. Trio medicine men recognize at least 75 distinct disease conditions—ranging from common ailments like fever [këike] to specific and rare medical conditions like Bell’s palsy [ehpijanejan] and distinguish between old (endemic) and new (introduced since contact with the outside world) illnesses. In an interview with mongabay.com, Lead author Christopher Herndon, currently a reproductive medicine physician at the University of California, San Francisco, says the findings are a testament to the under-appreciated healing prowess of indigenous shaman.

Research into drugs derived from natural products declining

(07/09/2009) Although the majority of drugs available today have been derived from natural products, research into nature-based pharmaceuticals has declined in recent years due to high development costs and the drug approvals process. However this trend is likely to reverse due to new approaches and technologies, according researchers from the University of Alberta.

(06/29/2009) Two drugs derived from rainforest plants in Sarawk (Malaysian Borneo) are now in their final stages of development, reports Bernama.

Colorful insects help search for anti-cancer drugs

(07/07/2008) Brightly-colored beetles or caterpillars feeding on a tropical plant may signal the presence of chemical compounds active against cancer and parasitic diseases, report researchers writing in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. The discovery could help speed drug discovery.

70% of new drugs come from Mother Nature

(03/20/2007) Around 70 percent of all new drugs introduced in the United States in the past 25 years have been derived from natural products reports a study published in the March 23 issue of the Journal of Natural Products. The findings show that despite increasingly sophisticated techniques to design medications in the lab, Mother Nature is still the best drug designer.

Indians are key to rainforest conservation efforts says renowned ethnobotanist

(10/31/2006) Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans -medicine men and women – who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. The combined loss of this knowledge and these forests irreplaceably impoverishes the world of cultural and biological diversity. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author (Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice, Medicine Quest) who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Hero for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. Plotkin believes that existing conservation initiatives would be better-served by having more integration between indigenous populations and other forest preservation efforts.