Using satellite data from the European Space Agency, researchers estimate that over 20% of juvenile Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Mexico were killed by the BP oil spill. Although that percentage may not seem catastrophic, the losses are on top of an 82% decline in the overall population over the past three decades due to overfishing. The population plunge has pushed the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to categorize the fish as Critically Endangered, its highest rating before extinction.

Given the perilous state of bluefin tuna worldwide, the US National Marine Fisheries Service announced in September, following the BP oil spill, that it would consider listing the species under the Endangered Species Act.

“This study confirms our worst fears about the oil spill’s impacts on bluefin tuna and provides more evidence that this species needs the Endangered Species Act to survive,” said Catherine Kilduff, an oceans program attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity. “The federal government could have predicted the effects of the spill during spawning season prior to the disaster; listing Atlantic bluefin tuna as endangered will prevent such an oversight from ever occurring again.”

Conservation groups and marine biologists have been pushing for a ban on bluefin tuna fishing for years, but to date the bluefin tuna regulating body—the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), has placed short-term industry demands over long-term population concerns, consistently overriding its own scientists’ recommendations on quotas.

Bluefin tuna hit another setback earlier in the year when a proposed trade ban failed the at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) after heavy lobbying from the Japanese. Japan is currently hosting the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), an international event meant to develop plans to stem the loss of biodiversity worldwide.

A report by WWF has warned that if fishing continues the bluefin tuna will likely be functionally extinct by 2012.

Related articles

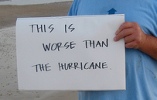

(07/29/2010) “President Obama called it ‘the worst environmental disaster America has ever faced.’ So I thought I should face it and head to the Gulf”—these are the opening words on the popular blog Guilty Planet as the author, marine biologist Jennifer Jacquet, embarked on a ten day trip to Louisiana. As a scientist, Jacquet was, of course, interested in the impact of the some four million barrels of oil on the Gulf’s already depleted ecosystem, however she was as equally keen to see how Louisianans were coping with the fossil fuel-disaster that devastated their most vital natural resource just four years after Hurricane Katrina.

History repeats itself: the path to extinction is still paved with greed and waste

(04/05/2010) As a child I read about the near-extinction of the American bison. Once the dominant species on America’s Great Plains, I remember books illustrating how train-travelers would set their guns on open windows and shoot down bison by the hundreds as the locomotive sped through what was left of the wild west. The American bison plunged from an estimated 30 million to a few hundred at the opening of the 20th century. When I read about the bison’s demise I remember thinking, with the characteristic superiority of a child, how such a thing could never happen today, that society has, in a word, ‘progressed’. Grown-up now, the world has made me wiser: last month the international organization CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) struck down a ban on the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna. The story of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is a long and mostly irrational one—that is if one looks at the Atlantic bluefin from a scientific, ecologic, moral, or common-sense perspective.

Critically Endangered bluefin tuna receives no reprieve from CITES

(03/18/2010) A proposal to totally ban the trade in the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna failed at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), surprising many who saw positive signs leading up to the meeting of a successful ban.