Gay Reinartz will be speaking at the Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd, 2010.

Unlike every other of the world’s great apes—the gorilla, chimpanzee, and orangutan—saving the bonobo means focusing conservation efforts on a single nation, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While such a fact would seem to simplify conservation, according to the director of the Bonobo and Congolese Biodiversity Initiative (BCBI), Gay Reinartz, it in fact complicates it: after decades of one of world’s brutal civil wars, the DRC remains among the world’s most left-behind nations. Widespread poverty, violence, politically instability, corruption, and lack of basic infrastructure have left the Congolese people in desperate straits.

“From a place of privilege, I have had the opportunity to look upon a society essentially reduced to its simplest, most fundamental term—survival. In Congo, I have witnessed wider extremes of cruelty and kindness, exploitation and generosity, revenge and forgiveness,” Gay Reinartz told mongabay.com in an interview. While developing and directing BCBI—a program established through the Zoological Society of Milwaukee (ZSM)—Reinartz has spent years working closely with Congolese communities in order to improve lives and, hopefully, ensure the long-term survival of the bonobo.

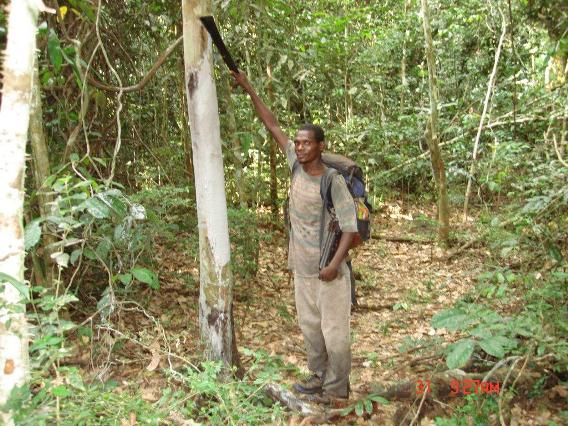

Gay Reinartz and Mboyo Bolinga in the Congo rainforest, the second largest in the world. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

From the moment Reinartz first met a troop of bonobos as they arrived at the Milwaukee Zoo, she was smitten. “They were charming,” she says of that encounter. Bonobos are most closely related to chimpanzees, but have been considered a separate species since the 1930s. While bonobos have some notable physical differences from chimpanzees, it is their behavioral differences that have really grasped the public imagination, especially their reputation of being lovers, not fighters.

“Bonobos have a playful nature. The idea that bonobos are a peace loving society is true—but to a certain extent,” Reinartz explains. “This trait is relative and must be seen in comparison to other great ape species. The media have overplayed bonobos as peaceniks. While it’s true that bonobos show less aggression, that they have less big-male domination, that ‘wars’ have not been observed, they do fight. […] Nevertheless, the bonobo has evolved ways to deal with social tension and reduce aggression or conflict—that being social sexual interactions—having intimacy and intercourse for reasons other than reproduction—and empathy.”

To save the world’s least known great ape, the BCBI has developed a number of initiatives. The organization has trained Congolese field workers to survey bonobo and other large mammal populations in Salongo National Park, providing baseline data for before and after conflict erupted in the region. The surveys are also studying different bonobo densities in a number of sites in the park, variously affected by poaching.

BCBI has also established programs to support protective measures in the park, including setting up an anti-poaching patrol, training park guards, and coming through with supplies and funds for park guards in emergencies. Reinartz says the situation is incredibly difficult for park guards, and often dangerous especially when facing elephant poachers.

A footprint of a bonobo. Photo courtesy Evelyn Vineberg. |

“There are fewer than two hundred park guards who are responsible for patrolling this entire area. They lack training, guns, means of transportation, communication, and basic forest equipment. There is approximately one gun per four men. They are no match for the well-armed elephant poachers who come in brandishing AK-47s.”

The biggest current threat to bonobos and most of the wildlife in the park is hunting: the great apes are killed for bushmeat as well as trapped in snares meant for other big mammals. Given the poverty of the region, and few ways to make money, the bushmeat trade has boomed in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“So, how do we convince them not to hunt? We have to give communities incentives to do something else and begin to build greater awareness. At the same time then, the park guards have to do their job in law enforcement. The two approaches must work from either side simultaneously—one with the other,” says Reinartz.

Giving communities incentives not to hunt includes working on providing new economic and education opportunities, both of which are basically non-existent in the region. BCBI has established a farming cooperative with a local NGO, helping villagers can learn to grow their own food and hopefully start up markets to sell the extra. The organization has also set-up primary schools, including providing materials and paying local teachers, and adult literacy courses. In such a region, if conservation is to succeed, conservation programs have to become humanitarian programs, filling in the role of a crippled government, a battered economy, and a region still suffering from bouts of violence. Part of the battle, says Reinartz, is convincing people that conservationists can be trusted, that BCBI won’t abandon communities if times get rough again.

“For many people, even though they might understand why and regret that elephants, bonobos and other animals have vanished from their communal forests, they consider conservation efforts as just another way they are being cheated and neglected. To change these attitudes will take a long time and program consistency to overcome generations of negative conditioning and hopelessness,” she says, adding that “what surprises me is that they aren’t more cynical than they are.”

Even in the face of war and poverty, Reinartz is clearly amazed at the generosity and strength of many of the Congolese people.

In a September 2010 interview Gay Reinartz spoke about the uniqueness of the bonobo, the challenge of saving a species in one of the world’s most forgotten places: the Congo, and of combining conservation work with humanitarian programs.

Reinartz will be presenting at the up-coming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd, 2010.

INTERVIEW WITH GAY REINARTZ

Mongabay: What is your background?

Gay Reinartz: I have been working for nearly 30 years in different capacities with bonobo conservation. I became acquainted with bonobos in the line of my work with the Zoological Society of Milwaukee. In 1988, I established the Bonobo Species Survival Plan (SSP, AZA) and coordinated it since, and I have been working in DR Congo since 1997. My training is in population genetics and evolutionary biology and my entire professional career has been focused in wildlife conservation. I obtained my PhD studying genetic variation in the bonobo. I developed and currently direct the Bonobo and Congo Biodiversity Initiative (BCBI)—a field conservation program that helps protect the bonobos in the Salonga National Park.

BONOBOS

Mongabay: What drew you to bonobos?

Reinartz conducts fieldwork with Etate park guards. Etate is the research station with the Zoological Society of Milwaukee. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: It was my job, really. I helped coordinate the importation of 7 bonobos to the Milwaukee County Zoo—the permitting process began in 1985. This was the point at which I began to do a lot of reading about the natural history of the bonobo, and I began to collect all the literature I could get my hands on. In 1986, I heard about a chimpanzee symposium down in Chicago at the Chicago Academy of Science. So I hitched a ride and attended the symposium called Understanding Chimpanzees, at which time I met chimpanzee and bonobo field researchers. I talked to them and became captivated with the bonobo story and the extreme problems the researchers and the species were facing. From a scientific standpoint, I was interested that bonobos came from a small, restricted range compared to that of other great apes—asking whether their genetic diversity would be inherently lower than the more wide-ranging chimpanzee. In December 1986, the bonobos finally arrived at the Milwaukee Zoo from the Netherlands. That night I met them, and I suppose my fate was sealed then and there. They were charming.

Mongabay: What are the major differences between bonobos and chimpanzees?

Gay Reinartz: There are many differences. From a conservation standpoint there is one major difference: bonobos are found only within the political boundaries of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and their future depends on what happens in this country. Physically, the bonobo is a slimmer, more refined and gracile chimpanzee. They have black skin, a hairstyle that parts in the middle and fans out sideways from their round head, and large side-whiskers. From a biological and a behavioral standpoint, studies suggest that bonobo society is more matriarchal than chimpanzee. Bonobo females tend to be more cohesive, and their cohesiveness can be a formidable force in calling the shots in everyday bonobo life. Yet bonobo society is flexible and dynamic, males often trump, depending on circumstances. We are still learning about these differences, and study of wild populations is extremely challenging for both species. Certainly one characteristic they share is that they are both endangered and both need our attention.

Mongabay: Are bonobos truly as peace-loving as their reputation suggests?

Gay Reinartz: Bonobos have a playful nature. The idea that bonobos are a peace loving society is true—but to a certain extent. This trait is relative and must be seen in comparison to other great ape species. The media have overplayed bonobos as peaceniks. While it’s true that bonobos show less aggression, that they have less big-male domination, that “wars” have not been observed, they do fight. Conflicts and attacks happen, and they can lead to some pretty serious injuries. My image of bonobos is not one of utter passivity. Crimes take place, and the guilty are severely punished! Nevertheless, the bonobo has evolved ways to deal with social tension and reduce aggression or conflict—that being social sexual interactions—having intimacy and intercourse for reasons other than reproduction—and empathy.

Mongabay: Will you tell us about your first encounter with these apes in the wild?

A bonobo nest in a tree. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: I was with a group of park researchers and our first BCBI director, Inogwabini Bila Isia. We were on a survey in the Salonga National Park in a place called Beminyo. We came upon a group of about 13 bonobos; it was early afternoon. I recall being dumbfounded standing there thinking how big they were. Then I went for my back pack fumbling to find my tape recorder. I crouched down shaking and following Inogwabini trying to get a better view. At first the bonobos started to scream from the treetops, and they were curious—all looking at us. I even thought then how easy they must be to shoot, since some of them were fully exposing themselves in order to check us out. Then, there was this wild scramble as the females dropped down the trunks and fled into the understory. A few males and sub-adults stayed behind and jumped enormous distances from tree to tree in the canopy, alternately hiding themselves and peeping out again. Then they too disappeared. The whole episode unfolded in 3 minutes or less. I had no camera, but I was able to record their calls on a tape recorder. When I go back and listen to that tape, I can hear myself in tears, thanking my partner, Inogwabini, for bringing me to this place.

Mongabay: What threats are bonobos facing in Salonga National Park?

Gay Reinartz: The greatest threat to any animal in the Salonga is hunting. In places, bonobos are pursued by hunters using guns and in other places bonobos succumb indirectly in snares and traps.

Mongabay: Are bonobos still threatened by the pet trade?

Gay Reinartz: Yes. As long as bonobos are hunted, babies will be taken alive. People will try to sell them in the hopes that they will bring a greater amount than they would as a small parcel of smoked meat. We continue to hear about or run across an orphaned bonobo about every two years—mostly while in major cities like Mbandaka and Kinshasa. If possible we intervene and work with authorities to send the bonobo to the sanctuary in Kinshasa, Lola ya Bononbo.

Mongabay: How imperiled is this species worldwide? How many survive in captivity?

An orphaned bonobo found in Mbandaka. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the only country where this species is found, bonobos probably number around 50,000, but this number has not yet been confirmed. One of the most urgent tasks we have as conservationists is to do surveys, locate bonobo populations, and estimate how many still exist in the wild. The areas that need to be surveyed are very remote, hard to get to, and often have some security risks. Nevertheless, a number of conservation groups are expanding their survey efforts. The threats facing the remaining populations are hunting, forestry, and commercial agriculture. It is estimated that over 40% of the bonobo’s range is slated for concessions to the forestry industry. Another threat is commercial farming: China searches for places to grow food for export to its population, and there is growing interest by many countries in palm oil conversion into bio-diesel fuel. This industry would clear large swaths of rainforest, sell the forest, and replant with oil palms.

There are about 231 bonobos in captivity; this includes approximately 50 that are kept in a sanctuary in the DRC. There are approximately 180 bonobo in zoos in North America and Europe. There are 81 in the US and Mexico.

SALONGA NATIONAL PARK

Mongabay: What makes Salonga National Park unique? What other endangered species are present there?

Gay Reinartz: Salonga is one of the world’s largest tropical forest parks; it is about 36,000 km2 covering a surface area larger than the country of Rwanda. The Salonga is the only national park that harbors bonobos. It was also once a regional stronghold of the endangered forest elephant, although their populations have been greatly diminished over the past couple of decades. The Salonga represents a whole ecosystem and the headwaters of some major rivers that feed millions of people. For this reason, because of the bonobo, and because of its legal status, I consider it the most important conservation site for the bonobo. It is important too for the forest elephants, at least six other primate species, rare ungulates such as the bongo, sitatunga, and the tiny water chevrotain, and the Congo Peafowl, a bird endemic to the region. The Salonga is also the only national park that protects part of a unique equatorial forest type—the one of the Cuvette Centrale or the central basin of the Congo River.

Sunset over Salonga National Park. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

The Salonga is absolutely beautiful. There are magnificent, meandering, black-water rivers that cut tree-lined corridors through rain forests. Trekking into the Salonga is like walking back a million years into a verdant, ancient land—where nature’s imagination is boundless and without a sense of proportion. All at once things are growing, dying, being born. Roots and vines, some as big as a man’s leg twist across the forest floor and up into the canopy. One sees flowers blooming on the trunks of trees; butterflies floating through the understory, dark-reds, blues and purples; brilliantly decorated, finger-sized caterpillars; blue-eyed frogs; fish with elephant-like proboscises; and trees, trees and more trees—a few giant ones that four linked men can not embrace. It is a large and untamed place. With its large swamps, many rivers, thick understory, it is a challenge to cross and easy to lose your way.

Mongabay: Has logging impacted the forests of Salonga National Park? Is it primarily locals for agriculture or industrialized logging?

Gay Reinartz: No. The forests of Salonga are virtually intact with the exception of some limited areas (southern sector) where different groups actually live in the park.

Mongabay: Is there enough funding and staff on the ground to adequately protect the wildlife and ecosystems in Salonga National Park from poachers and other human disturbances?

ICCN’s Chief of the Etate patrol post, Bokitsi Bunda, holding the snares and arrows the Etate guards confiscated on patrols. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: There are fewer than two hundred park guards who are responsible for patrolling this entire area. They lack training, guns, means of transportation, communication, and basic forest equipment. There is approximately one gun per four men. They are no match for the well-armed elephant poachers who come in brandishing AK-47s. Furthermore, there are no systematic patrols or ways to verify patrols. In fact, many of the guards hunt in the park themselves. Funding is only part of the problem—one has to be on the ground to understand the limitations of and verify the patrols. The park suffers from a lack of oversight and the ability to enforce policy.

One of our programs in BCBI is to train the guards in navigation techniques so they can literally find their way around the forest, leave trails and bushwhack to given destinations. We provide the maps, the training and instruction, equipment, and the follow-up. The guards use the maps and GPS to plan their patrol routes. As they go on patrol, they mark their path, mark the places they see bonobo nests, human signs and other wildlife. Later we download the data from the GPS. We can then tell where the guards actually went, what day, whether it corresponds to their data sheet, and where they observed key species. We make a map of the whole thing, and then the park wardens can direct anti-poaching activities to the most vulnerable places. In absence of this technique, guards must stay on trails, go places they know, and there is no way for them to pinpoint animal sightings. In this way, the guards make regular and systematic patrols, and we can verify their routes and locate places where bonobos congregate and where poaching might occur.

Mongabay: How dangerous is being a guard in Salonga National Park?

ZSM’s discovery of a shot forest elephant, tusks removed, on the Yenge River. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: It can be very dangerous in areas. There are sections of this park, zone rouge, where only the best armed and trained guards can venture. These are areas controlled by commercial elephant poachers—many backed by the military. Recently the ecoguards we support at the Etate Patrol Post were ambushed by poachers who were hiding out on the river. The poachers shot at our guards who quickly surrendered; then they beat them and took their equipment and guns. Miraculously they were set free and survived; many do not.

LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Mongabay: You traveled to Salonga during the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Has life for local residents significantly improved since then?

Gay Reinartz: No. These people have been deprived long before the civil war. This is an area where no roads exist, the agricultural sector has collapsed, and virtually all trade but fishing and hunting has disappeared. The villages might have a few more francs circulating among them, but if anything, their conditions are worse because of higher prices internationally. Still they face unimaginable poverty; few schools exist and they can not afford the fees; virtually no health care programs reach them, and they have no money for medicines; and they have little economic opportunity or trade.

Mongabay: How do you tell some of the poorest people in the world and in some cases literally starving that they shouldn’t kill bonobos or other endangered species for food?

BCBI’s adult literacy class in Bofoku Mai village. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: First of all, I don’t tell anybody what they can or cannot do or what they can or cannot eat. Your question is a good one because in reaction to it, I can emphasize that it is very important to be seen as a facilitator, someone who is trying to understand them and their local condition. Most people already know that it is illegal to kill bonobos and elephants—at least in the park. Most of the local villagers that I come into contact with are not after bonobos per se, but their snares kill indiscriminately and they would not lose an opportunity should they find one. Moreover, the hunting in the park is most often commercially based—very little of the meat is locally consumed by the hunter. The head, the skin, or the tail of an animal may be kept, but the rest is sold. So, how do we convince them not to hunt? We have to give communities incentives to do something else and begin to build greater awareness. At the same time then, the park guards have to do their job in law enforcement. The two approaches must work from either side simultaneously—one with the other.

Mongabay: What projects have the Bonobo and Congo Biodiversity Initiative (BCBI) set up with local villagers in the region?

Gay Reinartz: Over the years, we’ve set three programs based on many meetings with the local communities and their leaders.

Distributing equipment for the cooperate farming program. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

BCBI began a farming co-operative about six years ago. Decades ago people farmed in this region—these were mostly commercial farms that employed farm workers and the people benefited from wages and surplus. Today, people lack the skills, seed stock and basic equipment to farm as a means of income. The BCBI co-operative works with a local NGO (CLEXAS) to first organize farming units and then to train them in techniques of planting, crop rotation, seed production, harvesting, and storage. Furthermore, we are looking at ways to develop and transport produce to markets. Today there are about 230 households participating in the area, and for the first time they have surpluses of rice, manioc, and beans for sale.

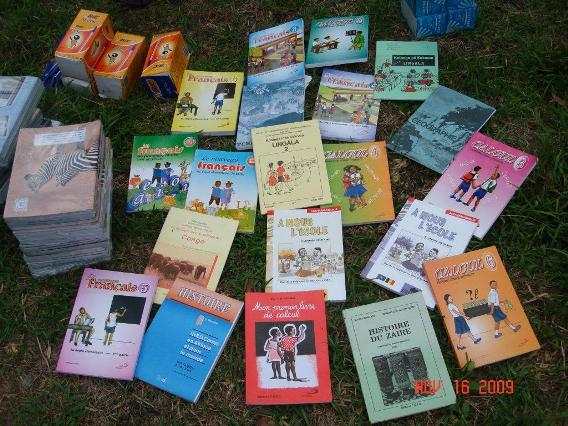

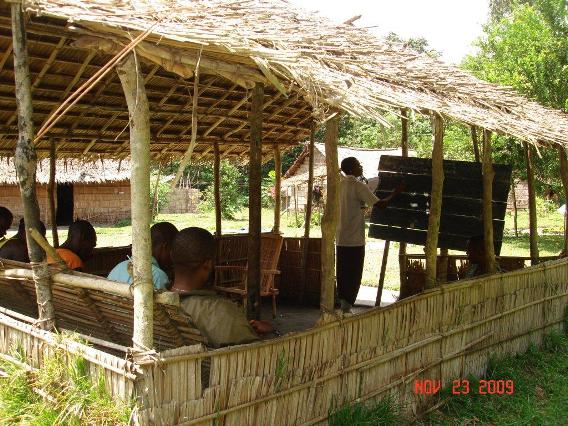

The second project involves revitalizing primary schools in villages surrounding the park. Most villages surrounding the park do not have primary schools and children must either live in the village or travel many kilometers to go to school. Most villagers cannot afford school fees which pay teachers salaries. So BCBI works with the villages to pay 7 primary school teachers, and annually we furnish school books and materials.

The third and most recent initiative is adult literacy. Over 90% of the adults in this area cannot read or write. This also includes the park guards. Originally, BCBI began a literacy program for the guards so that they could document patrols, but to our surprise most of the students were fishermen who stopped in from the local villages. So we expanded our outreach to hire two teachers to travel among the villages and give literacy classes. Today we have over 180 students, mostly women.

Mongabay: Why is it important to improve local lives when trying to save species on the edge like bonobos?

Gay Reinartz in a field GPS training session with an Etate park guard. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz. |

Gay Reinartz: The park guards (who come from the local population) and the people surrounding the park have the most invested in whether the bonobo lives and whether the park survives. They are among the most impoverished people in the world, and they will not accept that international and national resources are going into efforts designed to keep them out and away from a potential income. For many people, even though they might understand why and regret that elephants, bonobos and other animals have vanished from their communal forests, they consider conservation efforts as just another way they are being cheated and neglected. To change these attitudes will take a long time and program consistency to overcome generations of negative conditioning and hopelessness. What surprises me is that they aren’t more cynical than they are.

Mongabay: How has working with the people of the Congo changed you?

Gay Reinartz: I hope I have a better sense and understanding of humanity. (I don’t think I ever wore rose colored glasses, but if I did, they were long discarded.) From a place of privilege, I have had the opportunity to look upon a society essentially reduced to its simplest, most fundamental term—survival. In Congo, I have witnessed wider extremes of cruelty and kindness, exploitation and generosity, revenge and forgiveness. Extremes exist, and all too often violence has Congo by the throat. Yet, I think at their core, an individual prefers peace. I recall one voyage upriver and being so sick with food poisoning that I cold barely climb out of the pirogue. We had to stop at a small fishing camp because it was raining. When I had found my feet (with some help), I, a complete stranger and white person, staggered into the first hut, looked at the woman squatting by the fire, and immediately collapsed on her only bed. I watched her for awhile too weak to speak. She kept on cooking like this intrusion was normal. I slept on her bed all night. She kept the fire going. In the morning, never saying a word, she presented me with tea and an egg—all she had in reserve. That’s Congo.

To find out more about BCBI’s work: The Bonobo and Congolese Biodiversity Initiative

Large mammal survey by the ZSM research team in tandem with Etate guards – crossing an elephant bai. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

ZSM’s supply of elementary school books, notebooks and ballpoint pens for the village school of Tompoco. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

ZSM’s Etate research site andICCN patrol post. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

Etate park guards in a formal ZSM training session. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

ZSM’s supply of patrol equipment for the Etate guards. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

Rub-marks of a forest elephant against a tree in the Etate sector of Salonga National. Photo courtesy of Gay Reinartz.

Related articles

First captive bonobos released into the wild

(06/16/2009) A group of 17 orphaned bonobos are being released into the wild for the first time this month. Set free by the world’s only bonobo sanctuary, Lola ya Bonobo in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the bonobos will be released into a 50,000 acre (20,000 hectare) forest where the species has been absent for years.

New rainforest reserve in Congo benefits bonobos and locals

(05/25/2009) A partnership between local villages and conservation groups, headed up by the Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), has led to the creation of a new 1,847 square mile (4,875 square kilometer) reserve in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The reserve will save some of the region’s last pristine forests: ensuring the survival of the embattled bonobo—the least-known of the world’s four great ape species—and protecting a wide variety of biodiversity from the Congo peacock to the dwarf crocodile. However, the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve is worth attention for another reason: every step of its creation—from biological surveys to reserve management—has been run by the local Congolese NGO and villages of Kokolopori.

Flu epidemic killing bonobos in Congo sanctuary

(03/29/2009) Six bonobos, a species of chimpanzee, have died from a flu epidemic in a month at the Lola Ya Bonobo in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Ten more have contracted the flu. “There is no fever. Antibiotics don’t do anything. The bonobos have severe respiratory infections and then they can’t breath for 3 days then they die,” writes a staff member on the sanctuary’s blog through the conservation organization WildlifeDirect. The staff of Lola Ya Bonobo have sent out a plea for help and donations, as the flu continues to sweep through their center.

Rainforest Reserve Established in DR Congo to save bonobo

(11/19/2007) The government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has announced the creation of a 11,803-square mile rainforest reserve to protect the habitat of the endangered bonobo, the so-called “peaceful chimp”. The reserve is located in the Sankuru region, an area that experienced extensive fighting during the long-running civil war in the Congo.

Researchers head to Congo to study Bonobo psychology

(09/05/2007) Researchers have gone to the Democratic Republic of Congo to study the social behvaior of bonobos — a close relative of the chimpanzee — in the Lola ya Bonobo Sanctuary in Kinshasa.