One of the biggest ideas in the conservation world over the past decade is Payments for Environmental Services, known as PES, whereby governments, corporations, or the public pays for the environmental services that benefit them (and to date have been free), i.e. carbon, biodiversity, freshwater, etc. For example, Reducing Emissions through Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) is the largest such proposed PES concept, yet many others are emerging. However, a new study in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science argues that in order for PES to be effective—and not perversely lead to further harm—decision-makers must consider the danger of paying industrial and commercial interests versus financially supporting local populations, as originally conceived, to safeguard the environment.

“PES have traditionally been conceived and applied in contexts where the providers of the service are populations (as opposed to industrial companies) – fishermen, farmers, forest dweller,” write the authors, adding that “this inclination towards poor rural populations is logical for an instrument that leaves the initiative to a buyer whose interest is to best negotiate the provision of an environmental service.”

Initially PES was seen as an instrument that would conserve the environment while addressing economic inequalities and poverty, however increasingly other entities are becoming involved in selling ‘environmental services’ including investment firms and even big agricultural companies.

While the private sector, such as investment firms, have greater knowledge of markets and possibly better efficiency, such positive elements could be undercut by concerns of lack of transparency, loss of rights for local communities, and multiple contracts.

This new development also raises worries that industrial involvement will undercut the polluter pays idea whereby corporations involved in environmental degradation must pay for their actions.

“If the polluter pays principle is abandoned for the industry, the door will be open to all sorts of blackmail; the very fact of threatening an ecosystem will then become a serious business,” the authors write.

The study further warns that success of a PES may depend on its size, its relation to the law and the state governments, as well as the planned duration of payments.

“These risks must be taken seriously because the compulsive replication of this model is currently under debate, especially within the framework of the REDD+ mechanism. Its scope of application could therefore cover a major proportion of the forests situated in developing countries, which have carbon stocks that have now become a prime issue,” the authors write, adding that “a promising option to properly and effectively address these risks is to both specify and broaden the PES concept, and to reduce the scope of application when public financing is at stake.”

While the scientists call for more research, they argue for smart PES systems that both addresses environmental and development issues.

CITATION: Romain Pirard, Raphaël Billé, Thomas Sembrés. 2010. Upscaling Payments for Environmental Services (PES): Critical issues. Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 3 (3): 249-261.

Related articles

Is carbon protection the same as biodiversity protection?

(09/05/2010) Protection of forests for their carbon value through Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) schemes has been increasing in recent years. These schemes concentrate on preserving forest cover, and thus have great potential for the conservation of natural biodiversity. Some (REDD+) initiatives already specifically take biodiversity protection into account.

World Bank looking at ‘ecosystem-based approaches’ to infrastructure projects

(08/03/2010) Investments in protecting and managing biodiversity are key to helping the world slow and adapt to climate change, said a World Bank ecologist speaking last month at the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation meeting in Sanur, Bali.

Paying for nature: putting a price on ‘ecosystem services’

(07/12/2010) Ever since humans entered the stage, nature has been providing us with a wide-variety of essential and ‘free’ services: food production, pollination, soil health, water filtration, and carbon sequestration to name a few. Experts have come to call these ‘ecosystem services’. Such services, although vital for an inhabitable planet, have largely gone undervalued in the industrial age, at least officially. Yet as environmental crises pile one on another across the world, a growing number of scientists, economists, environmentalists, and policy-makers are beginning to consider putting a monetary value on ‘ecosystem services’.

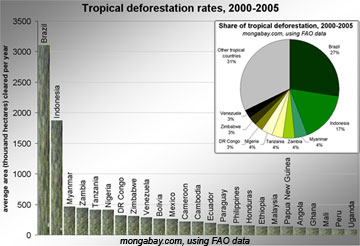

Tropical deforestation rates from 2000-2005, ranked in descending order by the highest amount of average annual forest loss for 25 countries based on data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Click image to enlarge.

Tropical deforestation rates from 2000-2005, ranked in descending order by the highest amount of average annual forest loss for 25 countries based on data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Click image to enlarge.