One of the world’s smallest frogs has been discovered living inside pitcher plants in Borneo, reports Conservation International, a conservation group that is jointly supporting a campaign with IUCN to search for some of the world’s “lost amphibians.”

The species, described in Zootaxa by Indraneil Das and Alexander Haas of the Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation at the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak and Biozentrum Grindel und Zoologisches Museum of Hamburg, is named Microhyla nepenthicola after the plant in which is was found, Nepenthes ampullaria, a species of pitcher plant from Malaysian Borneo. Many species of pitcher plants are carnivorous, relying on trapping of insects to supply nutrients otherwise not available in the resource-poor and acidic soils on which they typically grow. Nepenthes ampullaria instead subsists off decomposing organic matter that collects in its pitcher.

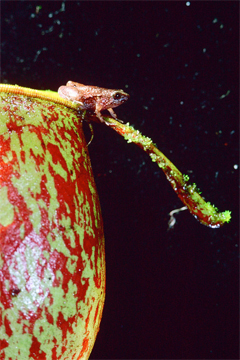

Microhabitat of the newly-discovered miniature frog species Microhyla nepenthicola showing patch of Bornean pitcher plant used for breeding by the frog. © Alexander Haas |

Microhyla nepenthicola lives in and around Nepenthes ampullaria. The frog deposit its eggs on the sides of the pitcher. When these hatch, the tadpoles grow in the liquid accumulated in the plant’s insect-trapping cavity.

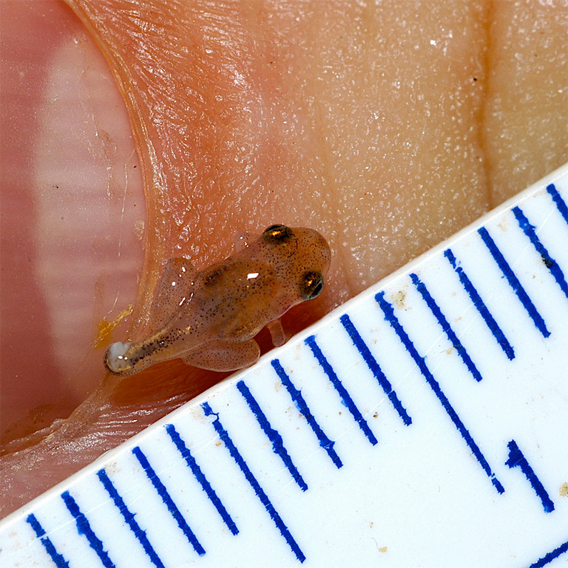

The new frog is a type of microhylid, a family of frogs under 15 millimeters in length. Adult males of the new species range between 10.6 and 12.8 mm or “about the size of a pea,” according to Conservation International (CI), which notes it is the smallest frog yet discovered in Asia, Africa or Europe.

The small size and obscure habitat of the the frog has left it unknown to science until now, although museum collections contained specimen that went unrecognized as a new species.

A newly-discovered species of miniature frog (Microhyla nepenthicola) sitting on the lip of a pitcher plant. © Indraneil Das/ Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation |

“I saw some specimens in museum collections that are over 100 years old. Scientists presumably thought they were juveniles of other species, but it turns out they are adults of this newly-discovered micro species,” said Das in a statement.

Researchers discovered the frog by tracking its call.

“The singing normally starts at dusk, with males gathering within and around the pitcher plants,” CI in an emailed statement. “They call in a series of harsh rasping notes that last for a few minutes with brief intervals of silence. This ‘amphibian symphony’ goes on from sundown until peaking in the early hours of the evening.”

The discovery comes as CI and IUCN’s Amphibians Specialist Group are gearing up to launch an effort to “rediscover” 100 species of “lost” amphibians – species presently considered “potentially extinct” but that may cling to existence in remote parts of the world. The “lost” amphibians campaign will be tracked at conservation.org/lostfrogs.

Indraneil Das heads a team that will search for for the Sambas Stream Toad (Ansonia latidisca) in Indonesia and Malaysia in September as part of the initiative. The toad was last seen in the 1950s and is believed to be a victim of increased stream sedimentation wrought by logging.

The campaign aims to highlight the plight of amphibians, which are in decline worldwide. Climate change, increased use of pesticides, habitat destruction, irresponsible collection for the pet trade, introduced species, and the outbreak of disease are believed to be major drivers of the extinction of nearly 200 frog, toad, salamander, and newt species since the 1980s. At least one-third of the world’s 6,000+ known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction.

This article erroneously described Nepenthes ampullaria as a carnivorous pitcher plant. In fact it is a detritivorous plant. Mongabay regrets the error.

Update 2: Mongabay has now been informed that Nepenthes ampullaria is at least partially carnivorous as originally stated. Reader Jonathan Moran notes: “As for N. ampullaria, technically, it’s both a detritivore and a carnivore- about 35% of its nitrogen is derived from fallen leaves; the balance is presumably made up from prey capture (they do catch insects, mainly ants, but at a very slow rate), and possibly root uptake.”

A juvenile of Microhyla nepenthicola, the Old World’s smallest frog and one of the world’s tiniest, on a scale bar. Adult males of this newly-discovered species range 10.6 and 12.8 mm. © Indraneil Das/ Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation |

Related articles

Scientists say amphibians are under grave threat due to climate change, pollution, and the emergence of a deadly and infectious fungal disease, which has been linked to global warming. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive status assessment of the world’s amphibian species, one-third of the world’s 5,918 known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction. Further, more than 170 species have likely gone extinct since 1980. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group is next.